Hello there! Apologies for the lack of post this fine weekend, we promise your regularly scheduled programming will be coming back shortly. But who are we to deprive you of any content? So I got to work, and here we have 30 different countries of the world of Camelot Lost, with their leadership all plotted out for you to consume. It's all broken up by region, and I'll tack on a very brief explainer. Let's do this!

NORTH AMERICA

UNITED STATES

1961-1964: Adlai Stevenson II (Democratic-IL)† / William Fulbright (Democratic-AR)

1964-1969: William Fulbright (Democratic-AR) / Robert F. Wagner Jr. (Democratic-NY)

1969-1977: Thomas Kuchel (Republican-CA) / John Lindsay (Republican-NY)

1977-1979: Jack Gilligan (Democratic-OH) / John Luke Hill (Democratic-TX)

1979-1981: Jack Gilligan (Democratic-OH)† / Martha Layne Collins (Democratic-KY)

1981-1989: Martha Layne Collins (Democratic-KY) / Walter Mondale (Democratic-MN)

1989-1997: Roy Cohn (Republican-NY) / Hank Grover (Republican-TX)

If you don't know what's going on in the United States... HOW?

CANADA

1957-1966: John Diefenbaker (Progressive Conservative)

1966-1975: Paul Martin Sr. (Liberal)

1975-1985: Robert Stanfield (Progressive Conservative)

1985-1991: John Crosbie (Progressive Conservative)

1991-????: Bob Rae (Liberal)

Dief the Chief manages to hang on grimly through a better campaign in '62 as the Stevenson administration announces that it's killing the Bomarc Plan during the Cuba negotiations, meant as a slight nudge to help Pearson (a kindred spirit to Adlai, really) but really just blowing up in the Grits' face as Dief rallies popular frustration at the perceived glibness the US is taking towards nuclear war. His next term is a bit of a disaster, though, and by 1966 the 72 year-old Diefenbaker is old news to the electorate. After some tense negotiations, the "Martin-Douglas" government is a massive expansion of the welfare state and a quiet revolution in public policy, but sectional tensions - especially in Quebec against the extremely Anglophone Grits - erode at the momentum behind upper-class social democracy. Everyone's Favorite Nova Scotian catches the football and hangs on grimly for ten years, becoming a renowned leader through no shortage of crises, but the constitutional reform efforts are his undoing as he steps out humiliated by their failure. Crosbie's got a foot in his mouth but he manages to salvage the reforms and with it his government, but a mild economic downturn and controversial trade agreements with the new Cohn administration destroy his remaining goodwill. Instead, the resurgent Grits find their way to a young MP from Ontario, a rising star who chose them over the Dippers way back when and built a profile in long-term opposition. Though his government's had its hits and misses, Canada's strong leadership in UNPROFOR gave him the boost he needed for re-election, and now we enter 1997 wondering whether time will vindicate the Rae of hope...

MEXICO

1958-1964: Adolfo López Mateos (PRI)

1964-1970: Gustavo Díaz Ordaz (PRI)

1970-1976: Alfonso Corona del Rosal (PRI)

1976-1982: Carlos A. Madrazo (ARD)

1982-1988: Porfirio Muñoz Ledo (ARD)

1988-1992: Elba Esther Gordillo (PRI)

Impeachment of Elba Esther Gordillo

1992-1994: Fernando Gutiérrez Barrios (PRI)

1994-????: Manuel Clouthier (PAN)

A largely-similar PRI rule goes through the early stages, but as popular opposition becomes galvanized it's hard to find a middle ground. Corona's crackdown is a bit like taking a sledgehammer to quicksilver, especially when the Madrazo faction - the "Democratic Current," as it were - splits the PRI in two to run its own campaign promising pluralistic reforms. Madrazo largely succeeds in democratizing, though his attempts at renovating the more permanent state are time-consuming and undermine other efforts. Allegations that Madrazo and Muñoz are simply the second head of the PRI seem unfounded at first but are much more so in the latter's term as a slow trickle of influence-peddling stories dominate the eternal power-seeker's attempts at reform. The PAN seems poised to finally rise to the occasion, but Elba's maneuvering manages to portray the ARD as little better than the old machine while simultaneously portraying her PRI as a new party. A controversial result sees institutional alquimistas effectively ensure her victory, but it seems an old dog can't learn new tricks as Gordillo is eventually impeached due to truly dizzying corruption and flees the country. Her successor cut his teeth in the "Dirty War" of the 1970s, and it shows as protests and uprisings are suppressed with sheer brutality. By the end of it, the people are exhausted, and the eternal anti-corruption opposition has its star candidate, so the result is hardly surprising but still heralds a newfound political pluralism...

SOUTH AMERICA

BRAZIL

1961-1961: Jânio Quadros (PTN)

1961-1965: João Goulart (PTB)

1965-1970: Juscelino Kubitschek (PSD)

1970-1980: Carlos Lacerda (UDN)

1980-1990: Leonel Brizola (PTB)

1990-????: Antônio Carlos Magalhães (UDN)

The core distinction comes when the United States refuses to send aid to putschists within the military. As Jango assumes presidential powers at last in 1963, they're still growing anxious, but their brief attempt at a direct overthrow sees a number of the colonels arrested by their superiors and Goulart's power protected. All is well in the wholesome South American democracy, right? Not quite, because while Stevenson-Fulbright aren't fans of coups they're no stranger to funding opposition campaigns, and JK is a familiar face in a sea of chaos. His return goes over well enough and sees some reform to cool the tensions, but by the end of it he's an old man and knows he's once again seen as a model of corrupt developmentalism. The military finds its time once again by throwing its tacit weight behind the outsider conservative governor, and Lacerda's Anos de Chumbo remain an infamous time of state repression, even if it had enough democratic legitimacy behind it. By its end, with the national economy in the toilet and the people furious, Brizolismo is just what the doctor ordered. A government grant for all of you! Post offices and hospitals in every favela! Combined with debt obligation negotiations between Brizola and Gilligan, the economic roar is felt by the end of the 80s. Even so, that civil-military-business alliance on the right is not to be denied, and Bahia's own ACM becomes a quintessential diplomatic triangulator (though UDN stalwarts will scream, only Tony could go to Havana) during Brazil's rise as an economic power in its own right...

CHILE

1958-1964: Jorge Alessandri (Independent)

1964-1970: Eduardo Frei Montalva (PDC)

1970-1974: Salvador Allende (PS)

Impeachment of Salvador Allende

1974-1976: Carlos Prats (Independent)

1976-1982: Patricio Aylwin (PDC)

1982-1988: Felipe Herrera (PS)

1988-1994: Orlando Letelier (PS)

1994-????: Sebastián Piñera (PN)

Chile's one of those cases where we probably spared a lot of heartache. Life continues as per the norm, with anti-Allende candidacies once again bankrolled by the US in lieu of extragovernmental action. By 1970, naturally, the cup of discontent runneth over, and no amount of frantic anti-Allende action can stop his victory. Life goes on, things go down to hell, but Rene Schneider's military remains stubborn (though Kuchel does try, dammit), and instead the coup is won through a stage-managed impeachment process. The developmentalism comes back after bloody instability under Aylwin (including a war with neighboring Argentina over the Beagle Islands, as mentioned in the TL) with the former UN SecGen as a popular candidate of the left with too much personal prominence to properly overthrow. Herrera and Letelier pick up where Allende left off, albeit less radically as to avoid his fate, but even then by the end of twelve years of it party fatigue and mounting inflation drive a certain young senator branded a huckster by the left and an optimist by the right to a rise far more meteoric than OTL...

ARGENTINA

1958-1963: Arturo Frondizi (UCRI)

Military coup overthrows Frondizi government

1963-1968: Gen. Raúl Alejandro Poggi

1968-1974: Juan Perón (PJ)†

1974-1988: José López Rega (PJ)

Mass protests result in end of López regime and open elections

1988-1994: Fernando de la Rúa (UCR)

1994-????: Domingo Cavallo (APR)

Sometimes, even a better man in Washington can't avert tragedy in Latin America. The horrendously unstable Argentine democracy sees even more controversy with the resolution in Cuba given Frondizi's overtures to Castro, and during the putsch against him the less democratic forces win. General Poggi's dictatorship is relatively brief as far as juntas go but is no less brutal, and by the time he's forced into direct elections even an attempt at meddling to stop the validity of the man in exile can't slow-walk his return. Peronism 2.0 is no kinder, and by the time the big man has his heart attack his stalwart deputy is here to kick in the last standing veneer of popular rule that Argentina has left. "El Brujo" rules like the occultist-fascist madman he is, even kicking off the Beagle Islands War and establishing a strong contender for the most brutal regime in the Western Hemisphere. By 1988, after war, repression, poverty, and the pariah status earned by the López regime takes its final toll, mass democratic action topples "Orthodox Peronism" once and for all. The democrats are no better at managing the fallout, though, and as we approach a new millennium the right's dour banker turned Cassandra is given his try at managing hyperinflation instead of the unpopular de la Rúa...

EUROPE

UNITED KINGDOM

1959-1963: Harold Macmillan (Conservative)

1963-1964: Quintin Hogg (Conservative)

1964-1969: George Brown (Labour)

1969-1977: Reginald Maudling (Conservative)

1977-1979: Edward du Cann (Conservative)

1979-1991: Peter Shore (Labour)

1991-????: David Owen (Labour)

Life goes as normal, with Supermac tossed out for much of the same reason - a better bit of campaigning puts Quintin Hogg in the seat he hoped to attain out of Macmillan's retirement. Even so, the split and wounded Tories are doomed in '64, and Labour's new leader - a rank Gaitskellite with a drinking problem - makes his way to No. 10. Brown's decision to join the EEC was deeply controversial and plenty of Eurosceptics blame American meddling (which is honestly correct, Bill Fulbright being himself), but the continuing economic and social strife combined with Brown's deeply uninspiring persona ultimately hobble his government. Maudling is a plodder but damned good at propping himself up, maneuvering his way between crises like Zimbabwe and the Bretton Woods recession alike. His chessmaster persona works quite well, but the ticking time bomb of scandal underneath him forces him into an early retirement, and the ineptitude of the arch-conservative du Cann all but assures defeat. The Labour Left being finally in control - having reconciled its image issues by propping up a socialist arguably more patriotic than 90% of the Tories - makes it a tad bit more narrow, but as Shore pulls Britain out of malaise and surges to historic popularity for his defense of Belize during the Guatemalan invasion in '84, his brand of leftism seems all but vindicated. Even so, his stubborn Euroscepticism and reneging on compromises made with the Labour Right during the early phases of his miinistry leads to David Owen's bad little fairies taking control for a brutal intraparty challenge. Though Owen fought his way from a major polling deficit to a mild victory in 1994, it's uncertain where Dracula - as opponents are fond of calling the severe, gaunt Owen - intends to go from here...

FRANCE

1958-1971: Charles de Gaulle (UNR)†

1971-1971: Alain Poher (CD)

1971-1978: Francois Mitterrand (FGDS)

1978-1992: Michel Poniatowski (FNRI)

1992-????: Jacques Delors (PGD)

France is a curious case, because we'll always have de Gaulle being de Gaulle. No matter what, that's a constant. What can change, though, is how long he hangs on. A slower boil amongst the student protest sections helps the General stay in power through the 60s, being his same erratic self even as the left unifies and grows more tired. His death in 1971 seems to many to be the moment to go for the top, and go for the top they do in the post-de Gaulle election. The Socialist-Communist alliance propping up Mitterrand is one that leads to a great many reforms, but is also not one without significant controversy. The economic crisis ultimately does him in, though, especially as strikes continue to cause trouble and the expulsion of the PCF mere months before the vote only serves to cause great strife in the left's coalition. Communists preferring to stay home instead of voting Judas only serves to get Michel Poniatowski in office, and the princely republican only turns up the unrepentant conservatism. The slow disintegration of the barrier between the National Front and the rest of the right is indeed controversial, but if the left can have communists than the right can add the far-right, some folks suppose. Eventually, though, a nation sick of the arch-conservative president and misadventure in promoting French hegemony in a rapidly-decolonizing Africa sees Delors as a different kind of social democrat, one of the gauche démocrate and a Christian leftist to boot, and elects to select his vision of a closely-knit social-democratic Europe over Poniatowski's hand-picked succession...

WEST GERMANY

1949-1963: Konrad Adenauer (CDU-CSU)

1963-1968: Ludwig Erhard (CDU-CSU)

1968-1976: Willy Brandt (SPD)

1976-1980: Franz-Josef Strauss (CDU-CSU)

1980-1986: Johannes Rau (SPD)

1986-????: Lothar Späth (CDU-CSU)

West Germany is largely a study in similarity, really. Though Erhard is able to plod along for longer than reality ever let him without Vietnam, by 1968 the impending fall of the government forces an election, and Willy Brandt rises much the same. Ostpolitik is no less controversial in our world, though with a more pliable GDR (more on that later) it goes over rather well, truth be told. The revelations around Guillame ruin the Brandt government in an otherwise-layup election, and the CSU's first Chancellor takes office... just as the Bretton Woods economy explodes. Not a great time for him. His role in the negotiations as a hard-charger for German interests win him some favorability at home, but in the end it's effectively undone when the glut of new defense projects unveils a staggering international Lockheed bribery scheme he's very much implicated in. Brother Johannes' intense religiosity makes him seem honest, a trait he plays up rather well campaigning against an embattled Strauss, and it nets the SPD a solid return. The return is not to last, though, as a gridlocked coalition leads to collapse and the popular Union candidate in Roman Herzog nets them a narrow government. From there, through crisis and calm alike, as the centrist Chancellor enters his eleventh year in office, he's effectively become an indispensible man at home and abroad...

ITALY

1960-1963: Amintore Fanfari (CD)

1963-1963: Giovanni Leone (CD)

1963-1971: Aldo Moro (CD)

1971-1975: Giulio Andreotti (CD)

1975-1976: Giovanni Leone (CD)

1976-1978: Francesco Cossiga (CD)

1978-1981: Enrico Berlinguer (PCI)

Second Republic established after “Golpe Bianco,” power shifted to presidency

1981-1991: Edgardo Sogno (PPI)

1991-????: Giulio Andreotti (PPI)

There are two men responsible for Italy in its current state: Count Edgardo Sogno and Aldo Moro. The former seems obvious, but the latter arguably heralded the Second Republic in his own right. As Moro negotiated a coalition of the center-left as Prime Minister, becoming one of the most long-lived leaders of the parliamentary system in the process, Italy prospered and Moro's popularity grew with it. Come time for a new presidential election in 1971, the Prime Minister was not shy about his desire to take the office, and the ruling coalition could absolutely back him as well. However, as the coalition melted down in his absence, slowly at first under the wily operator Giulio Andreotti then moreso under Leone and Cossiga, Enrico Berlinguer's rising PCI finally rose to a strong plurality, entering government in its own right. Moro's support for the Historic Compromise was essential in swearing Berlinguer in as the first Eurocommunist experiment. The right screamed when he targeted the banks their corrupt dealings flowed through, when the left-CDers in the coalition aided and abetted the Italian model of socialism, and when everything seemed to be going to hell with the neofascist brigades ramping up their attacks. As President Leone - Moro's replacement, and a more traditional Christian Democrat - sought to avoid indictment in the Lockheed scandal, his consulting with Count Sogno led to the controversial move to dismiss Berlinguer and appoint Sogno in his place at the helm of a broad government of the opposition. Sogno's constitutional reforms saw mass chaos as the Years of Lead came to their crescendo, but by the mid-eighties the presidential Second Republic had settled out with its new parties, most notably the big-tent right-wing People's Party. Even so, as a general strike over controversial economic reforms brought Italy to its knees, Sogno resigned office, allowing the ever-wily Andreotti - the leader of the Christian Democrats behind Sogno - to rise to the occasion in the ensuing presidential election, finally reaching the kind of power he had so desired...

SPAIN

1936-1974: Francisco Franco (FET)†

1974-1984: Luis Carrero Blanco (FET)†

1984-1990: Carlos Arias Navarro (FET)

Overthrow of Falangist regime, new constitution established

1990-1994: Íñigo Cavero (UDC)

1994-????: Miguel Herrero de Miñón (AP)

Though we talked about the long-term Falangist regime in the TL, it's worth reiterating just how much longer and bloodier the dissolution was here - instead of a gradual reform process engineered by a liberal king, we have a sort of zombie Francoism carrying Spain on until the public just can't take it anymore. The end result, a new Spanish republic - King Otto having engendered a much stronger anti-monarchist sentiment - is one still ruled by the right in this moment, with critics alleging that remaining Francoist elements and attempted electioneering by the United States helped to lock the PSOE's opposition leader Felipe González out of power. For his part, González has been unclear on whether he intends to contest the next election in 1998, though polls suggest that he's the most popular politician in Spain...

SOVIET UNION

1953-1968: Nikita Khrushchev (CPSU)

1968-1981: Yuri Andropov (CPSU)†

1981-1985: Nikolai Tikhonov (CPSU)

1985-????: Valentina Tereshkova (CPSU)

As Khrushchev remains in a stronger position in 1964, he's able to largely notice Brezhnev's attempted coup and put it off before it can begin. This lets Nikita continue doing what he loves best - being a tempestuous bastard. Even so, as he's routinely frustrated through the latter half of the 1960s, the space program seems a bit of a white elephant, and the Warsaw Pact develops a mind of his own, he's eventually deposed by the hardliners in favor of the KGB's new director Yuri Andropov. Andropov is a skilled operator, and though he invades Czechoslovakia to halt Alexander Dubcek's attempts at conducting independent diplomacy, he's able to largely break through institutional issues with sheer brutality. Routine corruption and inefficiency purges are horrendous to the average Soviet but do the job in keeping the country together (as well as the surge in national pride following the moon landing), but before Andropov can designate any sort of succession he passes away rather suddenly. With the knife-fighting between factions at a fever pitch, the party decides on a toothless idiot to fill the seat. It's a miracle Tikhonov survives any amount of time without doing anything ridiculous, but as the country seems on the brink of stagnating the first woman on the moon is able to leverage her status as a patriotic hero to rally a coalition of oddball reformists and kick the moron out. From there, the Tereshkova economic reforms - focused on high-tech innovation and limited deregulation - have seemed to work wonders in revitalizing the USSR, and the cosmonaut-turned-leader is an admired woman even as the western world recoils at the idea of such prominent communist leadership...

EAST GERMANY

1950-1967: Walter Ulbricht (SED)

1967-1979: Willi Stoph (SED)

1979-1990: Horst Sindermann (SED)

1990-1990: Hans Modrow (SED)

1990-????: Wolfgang Schwanitz (SED)

Ulbricht brings the wall up and draws Khrushchev's wrath as per the expectation. By 1967, Khrushchev tires of the old man and muscles him out of East Berlin, fearing that potential inter-German negotiations will be halted by Ulbricht. Willi Stoph proves an able successor and negotiator with Willy Brandt, and though the division seems here to stay the German situation is markedly less problematic by the time Stoph has also grown to retirement age. His chosen successor, an economic liberalizer, does just that in the face of mounting state debts and a serious slump, but this remains controversial with more conservative elements led by a grumpy aging Honecker. By 1990, Tereshkova hopes to build a new rapport with the west, and the end result is her stage-managing of Hans Modrow's rise to power to genuinely liberalize East Germany. Stasi elements are not pleased by the talk of social reform, though, and quickly engineer a scandal surrounding Modrow's alleged treason and depose him in favor of their leader. Now, it seems, East Germany is simply a Stasi playground...

POLAND

1957-1969: Władysław Gomułka (PZPR)

1969-1982: Edward Gierek (PZPR)

1982-1985: Czesław Kiszczak (PZPR)

1985-1996: Edward Babiuch (PZPR)

1996-????: Leszek Miller (PZPR)

The antisemitic crackdowns of the later part of Gomułka's time in office are a horrendous look for Poland and the Soviet Union overall, and as such the Gierek faction quickly rises to remove the hardliners and antisemites. Gierek's liberalization helps to promote Poland's image as a relatively prosperous Eastern Bloc nation, especially with the west suffering during the bitter late 70s recession. Like all not-as-terrible things, though, it must come to an end, and sure enough Gierek's decisions to negotiate with oppositionist factions brings the hardliners back to the forefront. The period of martial law only galvanizes the oppositionists, though, and through hardship it really begins to look like Poland is teetering. In one of her first moves towards being a "different kind of Soviet," Tereshkova quickly condemns Kiszczak's tactics and encourages leadership to turn over. Babiuch is unapologetically puppeted by Gierek, but this is alright with Moscow and the Polish people alike as Poland becomes something of a breeding ground for a new model of Warsaw Pact governance. By 1996, as Babiuch grows old, a young man in his image seems set to perpetuate the legacy of Gierek and Babiuch...

ROMANIA

1947-1965: Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej (PCR)

1965-1982: Ion Gheorghe Maurer (PCR)

1982-1990: Silviu Brucan (PCR)

1990-1996: Nicolae Militaru (PCR)†

1996-????: Ion Iliescu (PCR)

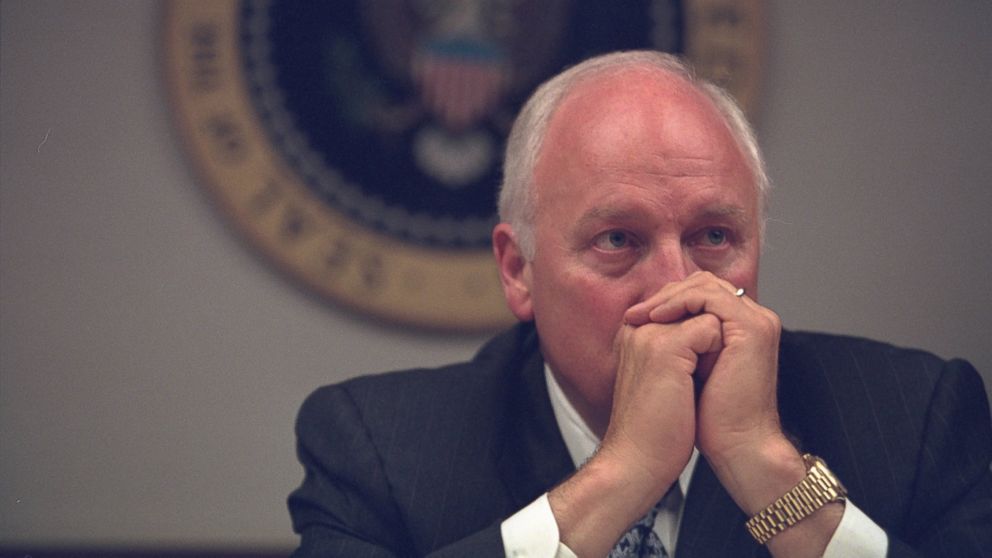

Yes, a lot of the NSF leadership ends up onsides with the PCR here, but that's what you get without Ceausescu. That's the true difference here - when Gheorghiu-Dej passes, Bucharest's approximation of Dick Cheney does a much better job rising to the occasion and sidelines Ceausescu the compromise candidate. Romania remains independently-minded in the bloc but is by no means outright flaunting Moscow's policies, which makes it at least acceptable to the Soviets compared to the strains of OTL. Brucan is one of the easiest lanes of communication between east and west as a diplomat by training, but when he retires after a health scare it takes the military's representation in the central government stepping in to stop the hardliners from asserting themselves. Militaru hangs on grimly through a bit of a crisis of confidence for Romania, but the level-headed leadership goes on until he's in the grave. From there, a young socialist with ideas he's dubbed "the Swedish model" is seeking to prove that the Warsaw Pact need not be a dour place...

ALBANIA

1944-1981: Enver Hoxha (PLA)†

1981-1993: Mehmet Shehu (PLA)†

1993-????: Ramiz Alia (PLA)

And now we have a case of failed-state communism. Hoxha is as quirky and independent as ever, Mao's favorite European and a true backwater of the Warsaw Pact (and only nominally involved to begin with). Bunkers dot the landscape, and eventually it's all too much to bear - so much so that his erstwhile deputy Mehmet Shehu poisons his mentor and takes his place. Shehu is no liberal, though, and now the crackdowns are simply aimed at keeping Albania's communists in power. It works for a while, even if the people are extremely unhappy and deathly poor. By the time Shehu himself is a dying old man, Ramiz Alia maneuvers himself to the big chair and looks at just how bad the situation is. By 1997, he's officially negotiating a transfer of power, and nobody knows what a "post-communist" state could possibly look like...

YUGOSLAVIA

1953-1979: Josip Broz Tito (SKJ)†

1979-1983: Edvard Kardelj (SKJ)†

1983-1993: Džemal Bijedić (SKJ)

1993-????: Ivan Stambolić (SKJ)

Josip Broz Tito is often seen as the only thing holding Yugoslavia together. Otherwise, what else does it have? Here, as Yugoslavia continues on much the same path as OTL, it doesn't seem like much. Tito's death going much faster through his health failure helps somewhat, as does the survival of his planned successor. Even so, the rumblings of Yugoslavia as a Serb state and local Serbs as feeling oppressed are very much felt. The rise of the Bosniak governor Džemal Bijedić to the big seat after Kardelj too succumbs to ill health seems precarious as well, but Bijedićism is a relatively simple doctrine - the stronger the economy goes up, the more stable a state is. His successes in reforming Bosnia to relative prosperity are brought nationwide, and while evenly-distributed investments don't remove the underlying contradictions that make up Yugoslavia it does lessen the pressure for secession short-term. By the mid-90s, the pressure for constitutional reforms has reached a fever pitch, and Stambolić and his cadre of pluralists (most notably "Buca" Pavlović) have their work cut out for them...

ASIA / OCEANIA

PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA

1949-1971: Mao Zedong (CCP)

1971-1983: Lin Biao (CCP)†

1983-1991: Hu Yaobang (CCP)†

1991-????: Mao Yuanxin (CCP)

Maoism has always been a complicated beast in the leftist world. The Mao-Fulbright talks infuriated Mao's own devotees, so much so that many argue that Mao felt that a Cultural Revolution was virtually the only way around the internal pressure (instead of the more complicated set of ideological motives). Regardless, the cut-off of the Open Door that more moderate leaders salivated over as a way to thumb their nose at the Soviet Union drove a ramshackle putsch, placing Lin Biao in charge against his will and ending the Revolution. Though Mao was quickly rehabilitated, the influence of his factionalists never truly was after the Taiwan Straits Missle Crisis, especially with his once-proxy Jiang Qing hauled out of power. The "Three Hus" moved to fill the vacuum, and their leader Hu Yaobang became undisputed in his rule of China after Biao's passing. Hu Yaobang's rapid liberalization was controversial to say the least, though the economic revitalization caused by it was undeniable. The problem was internal stability, with dissent spreading through China's variant of Akademset technology and rallying in universities around the country. Hu's attempts to dialogue with the students instead of sticking to the Maoist line infuriated conservatives, who plotted with the "magic name" behind Mao Yuanxin - the only unpurged member of Jiang Qing's faction - to stage a coup against Hu. Hu's death in custody sparked national protests, protests which were swiftly cut down by the unrestrained authoritarianism of Mao Yuanxin. Between the dynastic nature of its new leader and the rigidity of censorship in the newly-revolutionary China, many in the West feel comfortable calling it a "Hermit Empire..."

NORTH KOREA

1948-1978: Kim Il-sung (WPK)†

1978-1995: O Jin-u (WPK)†

1995-????: Yon Hyong-muk (WPK)

North Korea could have veered towards significantly worse. Kim Il-sung intended to pass power to his sons, but once Kim Jong-il became the only option the military was none too pleased by this development. Marshal O, the only man with comparable power to the Kims, hated the dilettante Kim Jong-il, and upon the elder Kim's death he moved to deny the boy his ability to seize power. The O Jin-u regime was a much more traditional communist state, one intensely nationalistic in its approach to neighbors like Japan and South Korea but also one designed around maintaining the relative prosperity North Korea had seen first and foremost. Kim having largely given up his dreams of power for himself, the succession instead went to the powerful premier - and moderate leader - Yon Hyong-muk. Now, Chairman Yon seems most concerned with negotiating with a newly-democratized South Korea, hoping to at last achieve the reunification that has eluded the peninsula for so long...

SOUTH KOREA

1960-1966: Chang Myon (Democratic)†

1966-1968: Yun Posun (Democratic)

1968-1971: Yu Chin-san (Democratic)

1971-1973: Kim Dae-jung (People’s)†

“Kim constitution” instituted via military coup, moved power to presidency

1973-1996: Gen. Kim Jae-gyu

1996-????: Lee Hoi-chang (New Korea)

Timely intervention by senior military leadership against General Park may have saved Korean parliamentary democracy, but it still remained unstable under near-unified Democratic Party rule. An ailing economic situation put diplomatic successes to shame, and the continual reshuffling of the Democratic Party's leadership saw them seen as largely ineffective rulers. The young new leader of the People's Party, Kim Dae-jung, was an electrifying presence in comparison to aging independence activists, and his "mass economy" was a deeply popular idea though ill-defined. Fearing socialism and his overtures to North Korea for reunification, though, a CIA-backed coup placed General Kim Jae-gyu - the only survivor of the purge against pro-Park generals - in power in South Korea, killing Prime Minister Kim in the process. Though General Kim ruled by decree for twenty-three years, following a referendum on the continuation of his government in 1995 being resoundingly rejected he opted to step away peacefully, allowing the anti-corruption conservative Lee Hoi-chang to lead South Korea's return to democracy...

INDIA

1947-1964: Jawaharlal Nehru (INC)†

1964-1971: Lal Bahadur Shastri (INC)†

1971-1982: Morarji Desai (INC)

1982-1983: Jagjivan Ram (INC)†

1983-1991: P. V. Narasimha Rao (INC)

1991-????: Sharad Pawar (INC)

Following Nehru's death, the Shastri government seemed poised for great things. Its agrarian reforms, ending of a border war with China, and overall popularity semeed to have it locked into place. Tragically, though, after seven years in power and multiple attempted killings - most notably a failed poisoning in Tashkent - Shastri passed away in a plane crash, leaving a power vacuum. Though some insiders resisted it, the conservative faction leader Morarji Desai managed to overpower the aging INC bosses with the connections he had built during the Shastri years, rising to the Prime Ministership in his own right. A platform of radical deregulation proved controversial in some sectors, but it also arguably set loose the Indian economic boom of the seventies and eighties. By the time an aging Desai was ready to retire, India's prosperity was high and its intervention in the Bangladesh Independence War had proven its regional influence, but the rising corporate economy was not popular in all sectors. To that end, the rural agrarian base had one man it wished to propel forward - Jagjivan Ram. Long a left-wing voice for the farmers, Prime Minister Ram's agricultural policy helped to continue the revolution started by Shastri two decades prior. It was not meant to be, though. Babu was cut down in perhaps the most infamous example of Khalistan liberationist violence, making a martyr for the Indian left and enshrining the rightwards tilt of the nation. Prime Minister Rao, elected in a hurry as a senior unifier, sought to dispatch the Punjab violence, and though he largely did manage to suppress it, he also continued Desaist reforms to the economy. Now, with a prominent dynast of the INC in office and India considered a rising "third pillar" due to its prominent economy, high population, and non-aligned politics, the sky seems the limit...

JAPAN

1960-1964: Hayato Ikeda (Liberal Democratic)

1964-1972: Eisaku Satō (Liberal Democratic)

1972-1979: Kakuei Tanaka (Liberal Democratic)

1979-1981: Saburo Eda (Socialist)

1981-1986: Kakuei Tanaka (Liberal Democratic)†

1986-1989: Noboru Takeshita (Liberal Democratic)

1989-1989: Kōzō Watanabe (Liberal Democratic)

1989-1991: Ryutaro Hashimoto (Liberal Democratic)

1991-1993: Michio Watanabe (Liberal Democratic)

1993-1996: Yōhei Kōno (Liberal Democratic)

1996-????: Shintaro Ishihara (Reimei)

It seems inevitable that Liberal Democratic hegemony would fade. Though the 60s saw a relatively popular and long-lived leadership, the controversial decision to allow Bill Fulbright to go ahead with his "self-determination" plan for Okinawa (a plan carried through by Kuchel for the purpose of maintaining the US military presence in the region) saw the current government largely rejected in favor of the insurgent Kakuei Tanaka. Tanaka would go on to be a giant of Japanese history, ruling through the controversial period of intense social repression after the Red Army fired upon the Emperor. In the end, though, his corruption would be undoing, as the scheme of almighty kickbacks with Lockheed led to the Tanaka government falling at the ballot box. The anyone-but coalition, led by the aging social democrat Saburo Eda, was not to last, and after its collapse a hastily-called election saw the very same Tanaka returned to power after controversially evading charges. Tanaka's rule would continue, the dizzying scale of corruption only growing under the construction mogul until his fatal stroke in 1986. From there, his faction - the effective majority of the LDP - carried on his legacy, burning through a number of new Prime Ministers for various kickback schemes and corruption scandals. The emergency of the 70s had awoken something, though, and as social reforms continued at home and the economy slumped, a sense of lost purpose seemed answered by the controversial nationalist party of Shintaro Ishihara and a faction of hawkish former Liberal Democrats: Reimei, or Dawn...

NORTH VIETNAM

1945-1967: Ho Chi Minh (CPV)†

1967-1985: Phạm Văn Đồng (CPV)

1985-1988: Trường Chinh (CPV)†

1988-????: Nguyễn Cơ Thạch (CPV)

After the Fulbright-Mao talks, North Vietnam was badly split. One faction wanted to negotiate a ceasefire to sort the new reality out, and another wanted to seek out increased Soviet aid in winning the war. Ultimately, the former prevailed, sending rising star Lê Duẩn out from his post and placing Ho Chi Minh loyalists in the old man's former seat. From there, the DRV's gerontocracy ambled onwards, largely withdrawing inwards apart from continuing tacit support for the Viet Cong in their ongoing rebellion against Saigon. By the time Phạm Văn Đồng's blindness had overcome him and Trường Chinh had passed, the reformist faction propelled upwards by the latter had firmly seized control with a relatively younger man. Now, as the Sino-Soviet split seems wider than ever, Nguyễn Cơ Thạch has begun to pursue a pragmatic - arguably neutralist - foreign policy while engaging in limited reform at home...

SOUTH VIETNAM

1955-1963: Ngô Đình Diệm (Cần Lao)†

1963-1964: Gen. Dương Văn Minh

1964-1964: Gen. Nguyễn Khánh

1964-1964: Gen. Dương Văn Minh

1964-1964: Gen. Nguyễn Khánh

1964-1965: Gen. Dương Văn Minh

1965-????: Nguyễn Cao Kỳ (Đảng Dân-chủ Tiến-bộ)

The fall of Diem was a hassle, to say the least. South Vietnam had become a mass of instability and corruption held together at the seams, and the constant switcheroo between generals running the dictatorship did not inspire confidence to say the least. As Washington tried its damndest to negotiate between the two sides, the struggle between old officers and young may have proven that instability is better than a cruel stability. Though the new government of the sixth-time's-the-charm coup of Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, firmly entrenched and with a fraught election behind it, was able to negotiate the ceasefire (with private assurance from Fulbright that the United States might get off his back a bit for human rights if he went through with it), the new Kỳ government was hardly one that could be considered likable. Broadly considered one of the most repressive dictatorships in the western orbit, Nguyễn Cao Kỳ's crackdown on dissent, "corrupt officials" who often just happen to be his opponents (though it did have the impact of purging much of the institutional rot that paralyzed the era before him), and belligerence due to seeming isolation as a pro-western dictatorship in a pink region, the thirty-year anniversary of Kỳ's coup has come and went with no signs of leaving the backwater of Southeast Asia...

AUSTRALIA

1949-1961: Robert Menzies (Coalition)

1961-1963: Arthur Calwell (Labor)

1963-1973: Harold Holt (Coalition)

1973-1979: Jim Cairns (Labor)

1979-1987: Joh Bjelke-Petersen (Coalition)

1987-1992: Mick Young (Labor)

1992-1993: Bill Hayden (Labor)

1993-????: Alexander Downer (Coalition)

A bit of a black sheep in the Anglosphere, Australia is often a rather right-wing country. Amidst a downturn in 1961, longtime Prime Minister Robert Menzies fell from power at last, resigning his leadership of the Coalition shortly after. Arthur Calwell's government proved fractious as divides between new and old within his party over a host of issues, from Calwell's socialist quasi-pacifism to the continuing of the White Australia policy, seemed like echoes of Adlai Stevenson and Bill Fulbright to American observers. The debonair Holt, long a minister for Menzies and a far more popular figure personally, was able to sweep this dissent aside to form a long ministry of his own, beating back the Labor reformer Gough Whitlam twice despite feverish campaigns from the latter. The Cairns government, by contrast, seemed the best of both worlds - the economics of Calwell and the social reformer's attitude of Whitlam. Dr. Cairns managed to bring a great many reforms to Australia, but was often hampered by an instransigent Senate and a fierce opposition. The right, long feeling that they were the natural party of government, was furious to say the least. Queensland's torrid Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen saw his moment as a figure with the adulation of businessmen everywhere, and converted his natural constituency into a campaign for the hearts and minds of desperate Liberals and Nationals everywhere. The Bjelke-Petersen government is nothing if not controversial for a bevy of reasons, whether it be intensely racialized quasi-totalitarian policing or obscenely right-wing economics, but the electoral malfeasance has to be the largest part of it. Though Joh refused to go down easy, a revolt by more moderate Liberals in the Coalition brought about an election and felled the beast. However, Mick Young's own skeletons - questionable donations, mostly - led to his own premature resignation just fourteen months before the next election, and his fellow moderate successor seemed no match for a resurgent Coalition with a young, smiling - if gaffe-prone - upper-class face attached to it...

AFRICA

EGYPT

1956-1970: Gamal Abdel Nasser (ASU)†

1970-1985: Ali Sabri (ASU)

1985-1991: Hussein el-Shafei (ASU)

1991-????: Boutros Boutros-Ghali (ASU)

Sometimes, it seems that Nasserism is just whatever Egypt does, and the more Egypt does it the more Nasserist it is. After Nasser himself passed in 1970, famously leading both Ali Sabri and Anwar Sadat to suffer heart attacks at his funeral, the former ultimately emerged victorious as a seeming vindication for the socialist wing of Arab Socialism. Most importantly, though, as the face of the Middle East changed in nuclear fire and the Muslim Brotherhood gained a foothold in revolutionary Arabia, the Nasserists grew fearful of their own loss of power, especially if the long-term goal of developing an Egyptian Bomb to counterbalance Israel was to be achieved. As such, when an ailing Ali Sabri sought to step down as to not die in office like Nasser, a term limit was put in place, hoping to ensure something akin to a Nasserist party dominance instead of a personalist one (privately, as well, Sabri wished to prevent the right-wingers from holding long-term power just by having a right-winger in the hot seat). After two peaceful successions, first from Sabri to the largely-agreeable Hussein el-Shafei and then to the right-wing at last with the Foreign Minister Boutros Boutros-Ghali, Egypt is poised to continue the tradition despite the relative instability in the Arab states...

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO

1960-1990: Patrice Lumumba (MNC)

1990-1995: Jean Nguza Karl-i-Bond (MNC)

1995-????: Marcel Lihau (MNC)

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is an interesting case study in decolonization. For nearly 15 years, a civil war unfolded between the two dueling governments, with Lumumba in the east and Kasa-Vubu in the west. The western world's lacking support for Kasa-Vubu, only made worse with a protracted power struggle between civilian government and General Mobutu's attempted coup, largely brought down the western government, while meanwhile Lumumba was a unifying figure for African revolution and one easy for Soviet and Chinese funding to flow to. By 1975, the western government had totally collapsed, ensuring that Lumumba was the undisputed master of the DRC. Though western detente with the DRC was slow due to the conflict in Angola and the building of state apparati in the country has been difficult, Lumumba's developmentalism and non-alignment has largely seemed to pay dividends in making the DRC a regionally influential nation. With the aging revolutionary's retirement in 1990 and death shortly after, the MNC's big-tent nature and unofficial term limit of five years (part of a delicate inter-factional balancing act) has ensured relative political stability in one of the hotbeds of colonial conflict...

SOUTH AFRICA

1958-1960: Hendrik Verwoerd (National)†

1960-1969: C. R. Swart (National)

1969-1978: Connie Mulder (National)

1978-1986: P. W. Botha (National)

1986-1989: Chris Heunis (National)

1989-1990: Joe Slovo (Congress Alliance)†

Military coup overthrows Slovo government

1990-1995: Gen. Magnus Malan

People’s Republic of South Africa established following fall of Cape Town and Gaborone Accords

1995-????: Chris Hani (SACP)

For ages, South Africa claimed some semblance of democracy amongst its white citizens. This, of course, was no democracy, but even it proved to be a sham. For decades, the National Party ruled, changing the authoritative face - Swart after Verwoerd was assassinated (only lethally shot by accident, the assassin purports), then Mulder once Swart stepped out due to age, then Botha once Mulder's truly heinous security state was revealed to the public, then finally Heunis once Botha the aging "human face" on apartheid was incapacitated. After the Heunis Plan for limited democratization took effect, the National Party was booted from office, replaced by the pieced-together Congress Alliance. The Alliance's leader, Joe Slovo, was a previous SACP member and avowed socialist, and this combined with talk of ending apartheid was too much to bear for National. Thus the facade ended and General Magnus Malan seized power, leading an even more unabashed authoritarian regime of enshrined white supremacy. The people rose in revolt behind the SACP, and the protracted civil war only ended when the "Cape Republic" Malan had proclaimed in a last-ditch effort for recognition fell to communist forces. Though the peace talks split the nation into four and the PRSA has few allies, at long last apartheid has ended it seems...

GLOBAL/OTHER

UN SECRETARIES-GENERAL

1953-1961: Dag Hammarskjöld (Norway)†

1961-1971: U Thant (Burma)

1971-1981: Felipe Herrera (Chile)

1981-1991: Sadruddin Aga Khan (France/Iran/Switzerland)

1991-????: Salim Ahmed Salim (Tanzania)

As much as the first two converge, the new presence of the PRC on the Security Council led to an emboldened bloc of support behind the "Global South" candidate, Felipe Herrera. Though the Kuchel administration refused to give Allende any support, the impasse refused to resolve itself, and eventually it seemed clear that the United States was lobbying for the PRC's removal to end the blockade. This, naturally, infurated the body, leading to a major backlash and forcing Kuchel to accede to Herrera's ascent with his tail between his legs. Even so, as tensions had cooled through the decade and a kinder, gentler America suggested a candidate, other negotiations saw to it that the Soviets and Chinese let the pick fly through. Finally, though, as Aga Khan's term came to an end, the movement for an African Secretary-General had only grown in its fervor, and after Malan's coup the intransigent Cohn administration knew it couldn't deny the African bloc. So it was that Tanzania's Salim Ahmed Salim making history by gaining what he had failed at attain ten years prior...

PAPACY

1958-1963: John XIII (born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli)†

1963-1980: Benedict XVI (born Franz König)

1980-????: Martin VI (born Eduardo Francisco Pironio)

Upon John XIII's death, many thought Cardinal Montini would be his successor. The rebellion of the reformists during the curia only led Montini to wish to withdraw, and though his backers tried quite hard to stop him it was no use. With their gambit successful, the reformists proposed their original candidate once again - a non-Italian Pope, the Austrian Franz König. Though this was a narrow and controversial vote, König was able to take the name Benedict XVI, hoping that he too would pursue peace like the last Benedict. His actions remain controversial with more conservative Catholics, such as his acceptance of the report of the Pontifical Commission on Birth Control, effectively allowing Catholics to use contraception (though Pope Benedict XVI still made clear the Church's staunch opposition to abortion). His missions through the Eastern Bloc, meant as a dialogue for peaceful coexistence, were inspiring to millions even as Nikita Khrushchev seemed to be watching the Pope's every word for any insult. Attempts at further reforming the Church were often stonewalled by conservatives in the institutions of the Vatican, frustrating the man who so hoped to make a modern Catholicism. This is why, citing a non-fatal heart attack, Pope Benedict XVI took the unusual step of resigning the office before his death, leaving in his wake the election of the first Latin American Pope, one who was close enough to Benedict for reformers and moderate enough for conservatives. Pope Martin VI has primarily focused on evangelism and humanitarian work, though he has spent some time quietly aiding in negotiating dictatorships in his home continent out of power. As Pope Martin VI grows old and sickly, though, it has become clear that a successor will likely be named soon to lead the Church into the new millennium...