English invasion of Scotland of 1385

The English invasion of Scotland of 1385 was the first military campaign led by King Edward V of England. The invasion was launched in retaliation to Scottish raids, which had grown more frequent and more destructive in the early 1380s. The campaign ran from 6 August to 16 September 1385, culminating in the Battle of Arkinholm.

Background

In the early 1290s, King Edward I of England was invited to arbitrate a dispute regarding the succession to the Scottish throne. Edward used the opportunity to assert his overlordship of Scotland before declaring John Balliol, lord of Galloway, to be King John of Scotland. Edward was an oppressive overlord. He reversed several rulings made by John, which provoked a rebellion by Scottish lords. The rebels found support in France, outraging Edward and prompting his invasion of Scotland in 1296. John was forced to abdicate as Edward attempted to annex Scotland outright, kicking off a decades-long war for control of the kingdom. The Scots rallied to Robert the Bruce, who was crowned King Robert I of Scotland. They threw the English out of the country and secured English recognition of Scottish independence in the 1328 Treaty of Northampton, bringing the First Anglo-Scottish War to an end.

Second Anglo-Scottish War

Robert I died in 1329. He was succeeded by his five-year-old son, King David II of Scotland. The following year, King Edward III of England staged a countercoup against Roger Mortimer, 1st earl of March, and took control of his own government. Edward blasted the Treaty of Northampton as a "shameful peace" soon after coming to power. He claimed that the treaty had been forced upon him by Mortimer and, as such, declared that he could not be held to its terms. This led to war again in 1332.

Edward III initially prosecuted his war against Scotland through the person of Edward Balliol, King John's son, who Edward III secretly supported in a campaign for the Scottish crown before he joined in hostilities directly in 1333. The two Edwards dominated the conflict with the Bruce loyalists, which ultimately brought France into the war in support of their ally, the young David II. The conflict between England and France became part of a larger set of issues between the two kingdoms, leading to the Hundred Years War.

In 1346, David II was captured in the Battle of Neville's Cross. He was held as a prisoner for more than a decade before being ransomed for 100,000 marks (£66,667). David struggled to pay his debt and, in 1369, agreed to a 15-year truce with England that included paying 4,000 marks annually toward his ransom. As a consequence of the truce, England's control of several key positions in Scotland was set to be unchallenged until 1384. David died suddenly in 1371, though, having only ever paid about half of his ransom.

Stewart dynasty

David II died childless and was succeeded by his nephew, Robert Stewart. The new King Robert II of Scotland was almost an old man by the standards of the day, taking the throne at age 55. He was more interested in securing his new dynasty than warring with England and agreed to honor David II's deal with the English, paying 4,000 marks per annum to keep the truce in effect through 1384. There were outbreaks of violence on the border occasionally, but these were generally small and local events. Robert discontinued payments to the English after the death of Edward III in 1377. That same year, George Dunbar, 10th earl of Dunbar, massacred the town of Roxburgh in one of the most remarkable outbreaks of border violence that decade.

In 1379, a small band of Scots burrowed into the wine cellar of Berwick Castle, surprising the small garrison there and briefly taking control of the fortress. The incident was deeply embarrassing for the English and it demonstrated just how much they had neglected border defenses after having renewed war with France. Scottish marcher lords took note and raids into English territory increased in the early 1380s. This was the same time that John Stewart, earl of Carrick, who was Robert II's eldest son and heir, was named lieutenant of the marches.

Carrick was the only one of Robert II's sons with major territorial interests south of the Forth and he acted as the crown's representative on the border long before he was made lieutenant. The marcher lords had been reluctant to accept the new Stewart dynasty upon Robert's succession, but Carrick won them over with marriage alliances and years of hard work. In time, Carrick's position became a double-edged sword. The marcher lords were more loyal to Carrick than to Robert, and Carrick was an ambitious man who was deeply uncomfortable being the middle-aged heir to an elderly king. His connections with the marcher lords made him hawkish in his dealings with the English and his father's truce with England became a dead letter.

In summer 1383, the Scots captured and partially demolished Wark on Tweed Castle. Lochmaben Castle was razed to the ground just months later. In early 1384, the English launched a punitive expedition led by Edmund of Langley, 1st duke of Aumale, and Thomas of Woodstock, 1st duke of Gloucester, to salvage the rapidly deteriorating situation. The dukes failed to bring the Scots to battle or take any major position. The expedition was costly, though, as a number of Englishmen died from exposure in a sudden cold snap.

England and France agreed to a six-month truce in summer 1383, just as hostilities broke out on the border between England and Scotland. The disconnect between French and Scottish policy was a sign of how far apart the two former allies had drifted over the course of Scotland's long truce with England, as Robert II repeatedly refused calls to join the war in the 1370s. The French found a new ally in Owain Lawgoch, the last male-line descendant of Llywelyn the Great, to threaten England from Wales, but Lawgoch was captured and killed fighting for the French in Gascony in 1377. The events of 1383 brought France and Scotland back together, as the two renewed their alliance. The Anglo-French truce was extended in early 1384, this time to include Scotland, which paused the conflict on the Anglo-Scottish border soon after the dukes of Aumale and Gloucester limped back to England.

The marcher lords abided by the new truce for a time, but they rebuked Robert II when the truce was extended to July 1385. Sir Archibald Douglas raided deep into Northumberland in open defiance of the Anglo-French treaty to which Scotland was now a party. French ambassadors at Robert's court followed news of the Douglas raid closely. They reported back to Paris that the English were ill-prepared to defend themselves and that Robert had little control over the marcher lords. Carrick, having already surpassed his father as the most influential figure on the border, soon supplanted Robert in dealings with the French as well, and plans got underway for a Franco-Scottish invasion of England upon the expiration of the truce.

In late summer, the dukes of Aumale and Gloucester arrived in Calais ahead of a long-planned conference with Jean, duke of Berry, and Philippe II, duke of Burgundy, at Leulinghem. This was supposed to be the highest-ranking set of talks since the Congress of Arras in 1375, but it never came to be. The French, already resolved to renewing hostilities the following year, dragged out negotiations on minor issues for several weeks. Aumale and Gloucester returned to England without ever meeting with Berry or Burgundy.

Preparations for war

On 29 September 1384, the English parliament assembled at Westminster Palace. Withering criticism of the regency council that had governed the kingdom in recent years led King Edward V of England to take over the government of the realm. He was 19 years old, past an age where he was expected to lead. His first major act was to reassert England's claims abroad, including its overlordship of Scotland. He declared he would lead a campaign north to bring the Scots to heel. The Commons agreed to grant taxation for the first time since 1380 to support the king's cause.

On 10 November, the Scottish parliament assembled at Holyrood Palace. A French offer to send 1,000 men-at-arms to support an invasion of England had widespread support, but Robert II was skeptical that France would actually follow through. He preferred to negotiate another truce with the English, but terribly misjudged the mood of the Scottish political establishment. James Douglas, 2nd earl of Douglas, moved to appoint Robert's son, Carrick, as lieutenant of the realm, vesting all diplomatic and judicial power in the heir to the throne. Parliament agreed. In addition to the military power he already wielded as lieutenant of the marches, the new position effectively made Carrick king in all but name.

Carrick wasted no time in making the new reality apparent to the English. The Scottish marcher lords were let off the leash, with devastating effects for northern England. Small towns and villages were burned and looted. Major positions were no better off. The English were not expecting war for more than half a year, which left the defenders of Berwick Castle unprepared for attack. The castle was taken by the Douglases before year's end.

French plan of attack

On 20 March 1385, King Charles VI of France assembled a war council to hash out the details of the coming invasion. A two-prong operation was envisioned. Jean de Vienne, admiral of France, would take an army to Scotland in the spring. He would join Carrick and the Scots in a campaign to take smaller positions on the border and harry the north of England. Olivier V de Clisson, constable of France, would bring a second, larger army to attack southern England in mid to late summer. Their hope was to draw the English north, denuding southern England of defenders and leaving the country open to Clisson.

The duke of Burgundy, who was the driving force behind the invasion, opened an entirely different line of attack in the run-up to the campaign. As count of Flanders jure uxoris, he instituted a boycott on English goods as he tightened his grip on the county. The results were immediately devastating. Royal revenue depended on the wool trade. The freefall in the wool staple offset the expected revenue from the grant of taxation.

Edward V, who had only reluctantly stepped up to lead in the parliament of 1384, proved to be a calm and confident leader through the unfolding crisis. He shrugged off the more reactionary members of his council as reports of Scottish raids flooded in. He would not be drawn into the war in the north before he was ready to fight. Instead, he responded to Carrick's violations of the truce in kind. England's northern powerhouses like the Cliffords, Nevilles and Umfravilles were given free rein against the Scots. Henry Percy, 4th baron Percy and warden of the eastern march, was ordered to retake Berwick before the king arrived for the summer campaign. No town on either side of the border was safe.

Edward was more aggressive and creative when it came to dealing with the duke of Burgundy. He refused to treat with Burgundy to save England's crumbling economy and instead did an end run around the duke. Sir Michael de la Pole was sent to strike a new trade agreement with Middelburg, a port city in Zeeland, that would keep English goods moving into the Low Countries and beyond. The city had both collaborated with and competed against the great trade cities of Flanders over the past century, and it had a vested interest in keeping English goods moving. This put Middelburg's wealthy townsmen at odds with their lord's regent, as Albrecht I, duke of Bavaria-Straubing, wanted closer relations with Burgundy and France, and even had a double marriage between his and Burgundy's children in 1384. From Middelburg, de la Pole traveled to Arnhem to bring the house of Jülich into an alliance against Burgundy. The Jülichs had supported the English in the past and, as one of the greatest families in the Low Countries, they felt threatened by Burgundy's increasing dominance of the region.

As de la Pole moved through the Low Countries, Edward received an embassy from the city of Ghent, where a 1379 revolt had led to uprisings across the whole of Flanders before being beaten back by the French crown in 1382. Ghent was, by 1385, the final holdout of the near-revolution. Edward sent the city's ambassadors home with 300 archers and 100 men-at-arms at their backs.

The duke of Burgundy carefully followed England's moves in the Low Countries, but he did not overly concern himself with them. Burgundy was an old diplomatic hand and he knew when his opponent was bluffing. The movement of English fighters into Ghent was an unwelcome development, but just 400 men could not save the city in the long run. The alliance with the Jülichs was also unwelcome, but the dukes of Jülich, Guelders and Berg were in no position to move against Flanders before July, when the second army was set to sail for England. Burgundy believed that, once the French invasion was underway and England was reduced to ash, the Jülichs would be compelled to reconsider their alliance with England.

On 25 May, Jean de Vienne landed at Leith with around 1,600 fighting men, plus hundreds—perhaps as many as 1,000—more in support staff. He also landed with 50,000 livres (£8,333), which he deposited into the Scottish treasury. Most of this was spread around to the Scottish lords who had turned out to support the French, but the rest was given over to Robert II to keep him quiet while Carrick and the French managed an invasion through Robert's kingdom without his input.

English plan of attack

On 4 June, Edward summoned a great council at Reading Abbey. The choice of location demonstrated the seriousness with which he was considering the coming campaign. The abbey was situated just 15 miles southeast of Wallingford, which had become his mother's favorite residence in her old age. Edward acknowledged that he may die on campaign in Scotland and had wanted to see his mother once more before he did. It was the second meeting of the Lords that year, another sign that the king had no illusions regarding the dangers he faced, and a demonstration of his commitment to rule with their support.

Edward issued a feudal levy for the campaign, calling on the magnates to muster at Newcastle on 14 July. In this, he exercised an ancient right of kings that had been all but forgotten. His grandfather, Edward III, had issued the last such levy in 1327 ahead of the Weardale campaign, which Roger Mortimer led in all but name and ended in a humiliating defeat by the Scots. The summons called upon every knight in the realm who held land to perform service in defense of the realm or to pay a fine in lieu of service. Edward V refused pleas to forgo the fine. He was thus able to outsource the cost of the campaign to the nobility by pointing to Burgundy's boycott and the strain that it had put on the English crown as his reason for doing so.

Edward named his 12-year-old cousin, Edward of Norwich, guardian of the realm for the duration of the campaign. It was a purely ceremonial position meant to note the person inside the kingdom who was the highest in the line of succession during the king's time abroad. Actual power was vested in a council led by Simon Sudbury, archbishop of Canterbury. Sir Thomas Holland, the king's half-brother, was charged with the defense of the realm in the king's absence. Holland was a highly competent figure who had served in many minor commands, but this was a major task. He ordered positions along the coast to make any necessary repairs and every coastal community from Cornwall to Norfolk to set up coast guards and place warning beacons on hilltops. Holland himself took up residence at Dover Castle with 600 men and fast horses, hoping that from there he could respond to calls for help.

On 23 July, Edward reached Newcastle. The response to the king's summons was overwhelming, as more than 14,000 men turned out to fight, supported by many thousands more attendants, pages, and servants. The king's royal uncles had the largest retinues, as John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster, had roughly 3,000 men in his service while the dukes of Aumale and Gloucester had around 1,000 each. Gaunt's son, Sir Henry of Bolingbroke, had his own retinue in addition to his father's. Edward's brother, Sir Richard of Bordeaux, had the smallest retinue of the royal family, but he had neither a great estate nor a wealthy heiress to support him, as his uncles and cousin did. About 1,000 men came in the service of two royal cousins by marriage, Edmund Mortimer, 3rd earl of March, and Robert de Vere, 9th earl of Oxford. More than 300 came under Thomas Beauchamp, 12th earl of Warwick, whose retinue was the largest from outside the royal family.

Scottish invasion of England

On 8 July, Carrick and Vienne led the Franco-Scottish army south from Edinburgh. The truce was not set to expire for another week, but it was still a later start to the campaign than either had wanted. Weeks were wasted by arguments between their captains, who disagreed as to how they should make war on the English. The French wanted to target major walled towns and small castles, but the Scots feared being bogged down by a siege and exposed to attack by the English, preferring to ride hard and fast across the country to inflict maximum damage and grow rich from cattle rustling. A compromise was eventually settled upon and sealed in an agreement between Carrick and Vienne, but the delay irritated leaders in both camps and the men in their armies grew to resent one another.

The Franco-Scottish army numbered about 4,600 men, of which nearly two-thirds were Scots. Its roster was almost as spectacular as that of the English army at Newcastle. Nine of Robert II's sons were a part of the campaign. Carrick led the army. He was joined by his most powerful brother, Robert Stewart, earl of Fife, their legitimate half-brothers David Stewart, earl of Strathearn, and Walter Stewart, earl of Atholl, plus five bastard half-brothers. The two great lords of the marches, George Dunbar, 10th earl of Dunbar, and James Douglas, 2nd earl of Douglas, were there as well, along with John Dunbar, 1st earl of Moray, and Archibald Douglas, lord of Galloway.

Carrick and Vienne led their men across the Tweed in the hopes of taking Roxburgh Castle, but found it too well defended. They moved on to Wark on Tweed Castle, which the English had retaken since its capture and partial demolition by the Scots two years earlier. Animosities that had been birthed by the delay in Edinburgh flared up during debate over the value of the castle. The French insisted on taking the position, but the Scots declared it worthless and refused to help. The French captured the castle on their own, as the Scots continued east along the march and massacred stragglers who had not yet fled the area.

The Siege of Wark was a major breach of trust for the French, who did not try to hide their hostility toward the Scots when they returned to the area. French captains declared that the Scots were "savages" lacking decency and honor. Vienne was more diplomatic in his dealings with the Scots, but his letters back to Paris were filled with a number of similar sentiments. The Scots were indignant. Five of the seven earls who had set out from Edinburgh with the French quit the campaign in protest, leaving only Carrick and his powerful ally, the earl of Douglas, behind.

Carrick and Vienne moved further east to attack Cornhill Castle and Ford Castle, but the English then began to move north from Newcastle. The Franco-Scottish army, which now had fewer than 3,000 men, retreated west before moving south to attack Carlisle instead.

French invasion of England

On 17 July, Charles VI wed Isabeau of Bavaria at Amiens. At Sluys, some 15,000 men were waiting to set sail for England. An embarkation date for the French invasion was set for 1 August. The great men of the realm were to move from Amiens to Sluys after the wedding festivities and lead the greatest invasion of England since Louis the Lion in 1216. Instead, the invasion was canceled the day after the celebration.

Frans Ackerman and Pieter van den Bossche, the last remaining leaders of the once-great Revolt of Ghent, used the occasion of the king's wedding to launch a surprise attack on nearby Damme. Supported by Sir John Bourchier, who led the 400 Englishmen sent to Ghent earlier in the year, they found the city was practically undefended. The captain of Damme was away organizing materials for the invasion and the leaderless garrison was completely unprepared for an attack. The Anglo-Ghentian force slaughtered the would-be defenders and the local population.

The loss of Damme immediately upset French preparations for war. The city's position on the canal system cut Sluys off from Bruges, stopping the flow of food and materials needed to survive while on campaign. On 18 July, Burgundy ordered the men at Sluys to move to Damme and retake the city. The siege stretched into late August before the Anglo-Ghentians abandoned the city and fled back to Ghent in the dark of night. By then, the French had eaten through too much of their food supplies to consider launching an invasion of England. Despite dire warnings from Vienne regarding his men falling out with the Scots, the admiral's expeditionary army was on its own.

English invasion of Scotland

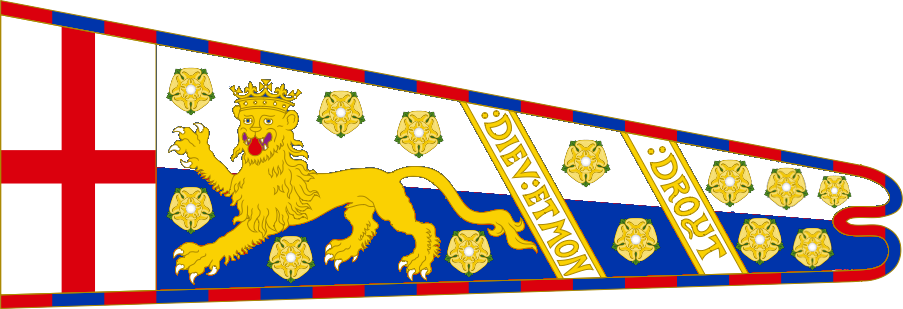

On 30 July, Edward led the English army out of Newcastle. He ordered his banners unfurled as they crossed the Scottish border on 6 August, revealing the Saint George's Cross and a crowned lion between six gold roses. The gold rose was a device first deployed in England by his great-great-grandfather, Edward I, a century prior. Its connection to the famed Hammer of the Scots made it a powerful symbol of Edward V's ambitions in Scotland.

On 30 July, Edward led the English army out of Newcastle. He ordered his banners unfurled as they crossed the Scottish border on 6 August, revealing the Saint George's Cross and a crowned lion between six gold roses. The gold rose was a device first deployed in England by his great-great-grandfather, Edward I, a century prior. Its connection to the famed Hammer of the Scots made it a powerful symbol of Edward V's ambitions in Scotland.

The Scots offered no resistance to the English. Robert II fled Edinburgh for the Highlands while the earls and other lords who'd quit the campaign in England dispersed to their own safe havens. What remained of the Franco-Scottish army slunk off toward the western march. Common Scots fled the English on their move north, taking everything of value with them. Edward marched the English on a six-mile front, destroying crops, homes, and whatever else they found. Even churches and monasteries were burned, the consequence of Scotland's obedience to the pope in Avignon.

Reaching Edinburgh without opposition on 11 August, Edward had the city razed to the ground. The defenders of the castle looked down helplessly as the royal palace burned. The king assembled a war council as Edinburgh was turned to ash. The lords could offer him no clear answer as to what he should attempt to do next. Edward had learned from the failure of his uncles Aumale and Gloucester in 1384 and ensured that the army was supplied by sea, meaning he could continue on campaign for weeks more if they remained close to the coast. A siege of Edinburgh Castle was considered, but the king's uncle, Gaunt, then recalled his disastrous experience besieging León on Lancaster's Crusade. He instead suggested moving north to cross the Forth. The English did not know the details of the French invasion plan, including their intended landing place, and news of Damme had not reached the army in Scotland. Gaunt thought the second French army may be intended for Scotland as well, and thus was suggesting they cross the Forth and put the Scottish coast to the torch all the way to the Firth of Tay so as to deny the French a port of entry. Gloucester disagreed, insisting that they move south to confront Carrick and Vienne, who were thought to be moving through Ettrick Forest. This drew sharp objections from the king's brother, Richard, who feared the Scots could be lying in wait in the forest.

According to the French chronicler Jean Froissart, Edward recalled the "Prophecy of the Six Kings" when choosing a course of action. It said that the sixth king that followed King John of England—i.e., Edward V—would be a cowardly mole whose line would be dispossessed of the crown. Among the forces that would bring down the sixth king was "a dragon from the north," which Edward believed symbolized the Scots. Edward, wanting to prove that he was not the coward that Merlin had foreseen, declared that he would go to meet Carrick and Vienne in battle, as Gloucester had suggested. He saw the strategic value of Gaunt's suggestion, though, and so decided to split the army.

The English army was divided three ways. Edward's uncles Gaunt and Aumale would lead the first division of about 4,000 men from Edinburgh to Sterling, destroy the town and round the Forth to lay waste to the whole coastline. The king's other uncle, Gloucester, would lead the second division of 4,000 down to Norham Castle, along with the earls of Arundel, March and Warwick and the marcher lords Neville and Percy. Together, they would sweep the marches from east to west and flush the French and Scots north. The king himself would lead the main army, about 6,000 strong, south through Ettrick Forest to attack the Scots or drive them east toward Gloucester's army.

The mission that Edward gave himself was the most dangerous of the three assignments by far. The fears that his brother, Richard, had voiced were not unfounded. English reports on the Franco-Scottish army's movements were sketchy at best, so it was certainly possible that Carrick and Vienne were luring the English into a trap. Ultimately, these fears were unfounded.

The French and Scots had crossed into Cumberland in mid August. Carrick and Vienne had agreed to make an attack on Carlisle before they arrived, but the French were again left to their own devices when the time came. The Scots made their way through Cumberland and into Westmorland, where Scottish raiders had not been seen in some time, promising rich booty for the Scots. The French launched their own attacks on Carlisle, but were twice repulsed with heavy casualties. The Scots later rejoined the French, but plans for a coordinated assault were abandoned when word arrived that Neville and Percy were approaching. Carrick and Vienne made a hasty retreat north, heading back the way they had come.

Battle of Arkinholm

On 7 September, the English and Franco-Scottish armies spotted one another near the village of Arkinholm in Dumfriesshire. Edward's men were hungry and tired. They had marched more than 70 miles through the hills and forest to cut off Carrick and Vienne's retreat north. It was hard terrain and moved the army away from the seaborne supply train, forcing them to survive on rations of salted meat and foraged food on their way.

Carrick and Vienne understood that they had been caught in a trap. Edward's army cut off their escape into the hills as Neville and Percy moved in from the east. Edward had twice as many men as the French and Scots, but the English were exhausted and the king was a green knight who had never fought a battle. French and Scottish captains agreed that their best course of action was to give battle, fearing that they would be overrun if Neville and Percy caught up to them and believing that the young king's inexperience could be his undoing.

The two armies arranged into battle formations. It was the first major battle between the English and either the French or Scots in many years. Edward, fearing that some overeager captain may break ranks and ruin the day, issued orders that any man who broke the line and survived would be hanged. In the end, it was the French who could not be controlled. Disagreements between the French and the Scots on battle tactics, and even between groups of Scots who wanted to organize traditional schiltrons and those who believed such a compact body of men would be easy targets for English archers, confused the men in the joint army. Either misunderstanding the plan or simply disregarding it, the French charged the English line before the Scots were ready. The disorderly French attack broke against the English line. Carrick, hoping to salvage the situation, ordered his men forward to support the French. The rush of Scots only added to the chaos, resulting in heavy casualties.

Edward ordered a counterattack, looking to crush his opponents before French or Scottish commanders had the opportunity to impose any sort of order. Sir Henry Percy, eldest son and heir of the baron Percy, cut his way through the French line and charged toward the Scots, personally clashing swords with Carrick. The earl of Douglas saw the battle was turning into a rout and ordered his men to retreat. Carrick was knocked from his horse in the mayhem that followed, breaking his knee. Englishmen began seizing French knights and taking them as prisoners. Most Scots fled, but Sir Thomas Erskine and Sir William Cunningham fought to defend their injured lord, Carrick, until he finally ordered them to lay down their swords and surrender. Around 500 French and Scottish men were killed, compared to fewer than 100 Englishmen.

Aftermath

Edward moved south from Arkinholm with his prisoners, which included Carrick, Vienne, and at least 250 others. He rested for a night at Carlisle, where the locals rejoiced at their change of fortune after having fended off Vienne just weeks earlier. Edward issued a summons for parliament to meet at York before making for Chester, imprisoning the heir to the Scottish throne far from the border.

Gaunt and Aumale devastated Scotland for more than a month after leaving Edinburgh in mid August. Their appearance north of the Forth caught many by surprise. It was the furthest that an English army had gone into Scotland in several decades. They returned to England on 16 September, having inflicted yet more destruction on Lothian as they returned south. Word of their kingly nephew's victory at Arkinholm and his summons for parliament likely reached the two dukes just as they returned to England.

The French and Scots were forced to suffer further humiliation before year's end. In mid September, a storm swept through the Channel as the great French armada at Sluys slowly dispersed, driving a dozen ships to shore near Calais. The English garrison there set upon the crews, taking some 500 men as prisoners and seizing their ships. Meanwhile, Carrick's allies organized a retaliatory campaign as English forces withdrew from Scotland. Some 200 Scots descended on Redesdale early in the morning of 4 October, but Sir Thomas Umfraville and his son, also named Thomas, led a spirited defense of the town, killing or capturing several dozen Scotsmen. Thomas the Younger was knighted by the king himself at parliament just weeks later.

On 27 October, parliament assembled at York. Edward was greeted with roars of approval from the Lords and Commons. He put Carrick and Vienne, his two highest-profile prisoners, on display. On his arm for the first time was his young wife, Giovanna of Naples, who had landed in England that summer, as Edward was crossing the border to Scotland. Swept up in the excitement of the king's victory, the Commons readily agreed to another grant of taxation to meet the threat of a possible French invasion in 1386.

The mood was far less celebratory when the Scottish parliament assembled on 8 November. It met at Scone as a result of the destruction of Edinburgh and Holyrood. The mood was sober. Carrick's lieutenancy of the realm had lasted less than a year and it had brought the greatest disaster upon the land since Edward III's Burnt Candlemas campaign of 1356. Many looked to Robert II's second son, Robert, earl of Fife, for leadership. Fife was no less ambitious than Carrick, and possibly moreso, but he had the good sense to reject calls for him to take up the mantle of lieutenant, not wanting to be associated with the unpopular decisions that would need to be made to clean up Carrick's mess. This led the aged Robert II, who was broadly unpopular for his appeasement of the English and his negligence in administering justice at home, to make the most unlikely comeback. Robert arranged for the French who had escaped capture at Arkinholm to return home before securing a six-month truce with England, which was set to run from New Years to 1 July 1386. Progress toward Carrick's release was slow, though, and the truce was soon extended until summer 1387. The marcher lords could hardly object to a pause in hostilities after Edward's punishing campaign.

Edward gladly welcomed Robert's offer of a truce, evidenced by the fact that it was negotiated in only a matter of weeks and put into force at the start of the new year. England had only narrowly avoided its own devastation at the hands of the French and Edward needed peace with the Scots to turn his attention to the threat he faced from across the Channel.

The French were undeterred by the failures of 1385. They believed that the loss at Arkinholm was the fault of the Scots, as Vienne's letters had predisposed them to the notion that their allies were simple brutes and brigands. They thought, as a result, that victory over the Scots had not required much skill on Edward's part, writing off his victory. The French likewise attributed the temporary loss of Damme to Ghent's rebel leaders, believing the English investment of arms too small to be significant. Such blatant disregard for England's achievements in 1385 left the French uncritical of themselves. As a result, they did not consider any strategic changes regarding the war with England, simply deferring invasion plans for a year.

One of the only areas in which French policy changed was in Flanders. The capture of Damme had exposed the risk that the rebels of Ghent posed, leading the duke of Burgundy to adopt a new, conciliatory approach in his dealing with them. Burgundy conceded to many of the city's demands for new rights and privileges, and even offered the rebels the protection of a royal pardon as a demonstration of his goodwill. The rebels, knowing that they could not hold out against the French forever and having been unimpressed that Edward sent them just 400 men under a knight of little renown, accepted the offer.

The alliance between France and Scotland was hugely strained by the failure of their joint campaign. The two countries remained allies on paper, but grew further apart than ever before. Their differences were not limited to matters of policy, as they had been in the 1370s. French knights who fought in Scotland painted a picture of a poor land full of backwards people. It became the conventional wisdom in Paris that the power of the Scots had been very seriously overestimated and that their inclusion in the 1385 invasion plan had only complicated matters. The French reevaluation of the Scots led to heated diplomatic exchanges when, in 1386, Robert II argued that the agreement that Carrick and Vienne had signed in Edinburgh had made Carrick a retainer of Charles VI, thus obligating the king of France to pay Carrick's ransom.

Impact

The 1385 English invasion of Scotland was much celebrated by contemporary English writers, but received only passing mentions in French sources. This reflects its relative importance on the war efforts of the two kingdoms. As historian Nigel Saul noted in his biography of Edward V, the English had achieved a major goal in relieving pressure on their northern border, but this "hardly affected the balance of power between England and France." The French had dominated the English during the long Anglo-Scottish truce, having reconquered most of Aquitaine, resubjugated Brittany, and dispossessed the king of Navarre of his lands in France in the 1370s and early 1380s. The French thus had no reason to believe that Scotland exiting the war again in 1386 would significantly impact their own war effort.

The invasion rewrote the politics of England and Scotland, though. The nascent peace party that had formed in the English Commons immediately disappeared while Scottish war hawks fell silent for a time. Marcher lords on both sides of the border remained hostile to one another, but outbreaks of violence became infrequent and, except for a major confrontation in 1388, were much smaller in scale.

The finances of the English crown were transformed at a stroke. Edward borrowed a substantial sum from his uncle, Gaunt, who had returned from Lancaster's Crusade flush with cash, to buy the rights to ransom nearly every one of the men captured at Arkinholm. This quickly put money in the pockets of the English who had taken prisoners in battle while positioning the crown to make a windfall by negotiating more than 200 ransoms. That a disproportionate number of those captured were French, who typically brought higher sums than Scottish captives, made the haul of prisoners especially lucrative. Vienne brought 100,000 francs (£16,667) to the English treasury on his own, owing to his position as admiral of France. Carrick, as heir to the throne of Scotland, was the greatest prize, though.

Negotiations over Carrick's ransom dominated Anglo-Scottish relations in the mid to late 1380s. Robert II had an extraordinarily weak hand in talks. The old king turned 70 when talks for his eldest son and heir's release began in spring 1386, putting enormous pressure on the Scots to get a deal quickly for fear that Robert would die with Carrick still in English custody. At the same time, though, the Scottish treasury was unable to meet the demands being made by England. This led Robert to assert that Carrick had fought on retainer for Charles VI in an attempt to put the financial burden of Carrick's release on the French. This was not well-received in Paris, but the French did eventually agree to send another installment of 50,000 livres (£8,333) to Robert II in order to avoid a more serious breakdown in Franco-Scottish relations. In 1389, his ransom was finally agreed for 60,000 marks (£40,000), plus the 32,000 marks (£21,333) still outstanding from David II's ransom.

The campaign also had a profound impact on the English nobility. It was a coming of age for a whole new generation of young men. Edward V, aged 20 at the time of the battle, was still technically a year shy of his majority, but had stepped into his own power. At his side at Arkinholm were Sir Henry of Bolingbroke and Sir Henry Percy, who would become two of the greatest heroes of Edward's generation, and many more. The speed with which Percy smashed through the French line and charged Carrick became the subject of a popular bard's song, earning Percy the nickname "Hotspur." In 1386, Edward established a new chivalric order for his "brothers in arms," the Order of the Bath, which was kept exclusively for men who had fought with the king in battle. Upon its founding, that included only those who had been at Arkinholm and the 1386 Battle of Écluse.

The English invasion of Scotland of 1385 was the first military campaign led by King Edward V of England. The invasion was launched in retaliation to Scottish raids, which had grown more frequent and more destructive in the early 1380s. The campaign ran from 6 August to 16 September 1385, culminating in the Battle of Arkinholm.

Background

In the early 1290s, King Edward I of England was invited to arbitrate a dispute regarding the succession to the Scottish throne. Edward used the opportunity to assert his overlordship of Scotland before declaring John Balliol, lord of Galloway, to be King John of Scotland. Edward was an oppressive overlord. He reversed several rulings made by John, which provoked a rebellion by Scottish lords. The rebels found support in France, outraging Edward and prompting his invasion of Scotland in 1296. John was forced to abdicate as Edward attempted to annex Scotland outright, kicking off a decades-long war for control of the kingdom. The Scots rallied to Robert the Bruce, who was crowned King Robert I of Scotland. They threw the English out of the country and secured English recognition of Scottish independence in the 1328 Treaty of Northampton, bringing the First Anglo-Scottish War to an end.

Second Anglo-Scottish War

Robert I died in 1329. He was succeeded by his five-year-old son, King David II of Scotland. The following year, King Edward III of England staged a countercoup against Roger Mortimer, 1st earl of March, and took control of his own government. Edward blasted the Treaty of Northampton as a "shameful peace" soon after coming to power. He claimed that the treaty had been forced upon him by Mortimer and, as such, declared that he could not be held to its terms. This led to war again in 1332.

Edward III initially prosecuted his war against Scotland through the person of Edward Balliol, King John's son, who Edward III secretly supported in a campaign for the Scottish crown before he joined in hostilities directly in 1333. The two Edwards dominated the conflict with the Bruce loyalists, which ultimately brought France into the war in support of their ally, the young David II. The conflict between England and France became part of a larger set of issues between the two kingdoms, leading to the Hundred Years War.

In 1346, David II was captured in the Battle of Neville's Cross. He was held as a prisoner for more than a decade before being ransomed for 100,000 marks (£66,667). David struggled to pay his debt and, in 1369, agreed to a 15-year truce with England that included paying 4,000 marks annually toward his ransom. As a consequence of the truce, England's control of several key positions in Scotland was set to be unchallenged until 1384. David died suddenly in 1371, though, having only ever paid about half of his ransom.

Stewart dynasty

David II died childless and was succeeded by his nephew, Robert Stewart. The new King Robert II of Scotland was almost an old man by the standards of the day, taking the throne at age 55. He was more interested in securing his new dynasty than warring with England and agreed to honor David II's deal with the English, paying 4,000 marks per annum to keep the truce in effect through 1384. There were outbreaks of violence on the border occasionally, but these were generally small and local events. Robert discontinued payments to the English after the death of Edward III in 1377. That same year, George Dunbar, 10th earl of Dunbar, massacred the town of Roxburgh in one of the most remarkable outbreaks of border violence that decade.

In 1379, a small band of Scots burrowed into the wine cellar of Berwick Castle, surprising the small garrison there and briefly taking control of the fortress. The incident was deeply embarrassing for the English and it demonstrated just how much they had neglected border defenses after having renewed war with France. Scottish marcher lords took note and raids into English territory increased in the early 1380s. This was the same time that John Stewart, earl of Carrick, who was Robert II's eldest son and heir, was named lieutenant of the marches.

Carrick was the only one of Robert II's sons with major territorial interests south of the Forth and he acted as the crown's representative on the border long before he was made lieutenant. The marcher lords had been reluctant to accept the new Stewart dynasty upon Robert's succession, but Carrick won them over with marriage alliances and years of hard work. In time, Carrick's position became a double-edged sword. The marcher lords were more loyal to Carrick than to Robert, and Carrick was an ambitious man who was deeply uncomfortable being the middle-aged heir to an elderly king. His connections with the marcher lords made him hawkish in his dealings with the English and his father's truce with England became a dead letter.

In summer 1383, the Scots captured and partially demolished Wark on Tweed Castle. Lochmaben Castle was razed to the ground just months later. In early 1384, the English launched a punitive expedition led by Edmund of Langley, 1st duke of Aumale, and Thomas of Woodstock, 1st duke of Gloucester, to salvage the rapidly deteriorating situation. The dukes failed to bring the Scots to battle or take any major position. The expedition was costly, though, as a number of Englishmen died from exposure in a sudden cold snap.

England and France agreed to a six-month truce in summer 1383, just as hostilities broke out on the border between England and Scotland. The disconnect between French and Scottish policy was a sign of how far apart the two former allies had drifted over the course of Scotland's long truce with England, as Robert II repeatedly refused calls to join the war in the 1370s. The French found a new ally in Owain Lawgoch, the last male-line descendant of Llywelyn the Great, to threaten England from Wales, but Lawgoch was captured and killed fighting for the French in Gascony in 1377. The events of 1383 brought France and Scotland back together, as the two renewed their alliance. The Anglo-French truce was extended in early 1384, this time to include Scotland, which paused the conflict on the Anglo-Scottish border soon after the dukes of Aumale and Gloucester limped back to England.

The marcher lords abided by the new truce for a time, but they rebuked Robert II when the truce was extended to July 1385. Sir Archibald Douglas raided deep into Northumberland in open defiance of the Anglo-French treaty to which Scotland was now a party. French ambassadors at Robert's court followed news of the Douglas raid closely. They reported back to Paris that the English were ill-prepared to defend themselves and that Robert had little control over the marcher lords. Carrick, having already surpassed his father as the most influential figure on the border, soon supplanted Robert in dealings with the French as well, and plans got underway for a Franco-Scottish invasion of England upon the expiration of the truce.

In late summer, the dukes of Aumale and Gloucester arrived in Calais ahead of a long-planned conference with Jean, duke of Berry, and Philippe II, duke of Burgundy, at Leulinghem. This was supposed to be the highest-ranking set of talks since the Congress of Arras in 1375, but it never came to be. The French, already resolved to renewing hostilities the following year, dragged out negotiations on minor issues for several weeks. Aumale and Gloucester returned to England without ever meeting with Berry or Burgundy.

Preparations for war

On 29 September 1384, the English parliament assembled at Westminster Palace. Withering criticism of the regency council that had governed the kingdom in recent years led King Edward V of England to take over the government of the realm. He was 19 years old, past an age where he was expected to lead. His first major act was to reassert England's claims abroad, including its overlordship of Scotland. He declared he would lead a campaign north to bring the Scots to heel. The Commons agreed to grant taxation for the first time since 1380 to support the king's cause.

On 10 November, the Scottish parliament assembled at Holyrood Palace. A French offer to send 1,000 men-at-arms to support an invasion of England had widespread support, but Robert II was skeptical that France would actually follow through. He preferred to negotiate another truce with the English, but terribly misjudged the mood of the Scottish political establishment. James Douglas, 2nd earl of Douglas, moved to appoint Robert's son, Carrick, as lieutenant of the realm, vesting all diplomatic and judicial power in the heir to the throne. Parliament agreed. In addition to the military power he already wielded as lieutenant of the marches, the new position effectively made Carrick king in all but name.

Carrick wasted no time in making the new reality apparent to the English. The Scottish marcher lords were let off the leash, with devastating effects for northern England. Small towns and villages were burned and looted. Major positions were no better off. The English were not expecting war for more than half a year, which left the defenders of Berwick Castle unprepared for attack. The castle was taken by the Douglases before year's end.

French plan of attack

On 20 March 1385, King Charles VI of France assembled a war council to hash out the details of the coming invasion. A two-prong operation was envisioned. Jean de Vienne, admiral of France, would take an army to Scotland in the spring. He would join Carrick and the Scots in a campaign to take smaller positions on the border and harry the north of England. Olivier V de Clisson, constable of France, would bring a second, larger army to attack southern England in mid to late summer. Their hope was to draw the English north, denuding southern England of defenders and leaving the country open to Clisson.

The duke of Burgundy, who was the driving force behind the invasion, opened an entirely different line of attack in the run-up to the campaign. As count of Flanders jure uxoris, he instituted a boycott on English goods as he tightened his grip on the county. The results were immediately devastating. Royal revenue depended on the wool trade. The freefall in the wool staple offset the expected revenue from the grant of taxation.

Edward V, who had only reluctantly stepped up to lead in the parliament of 1384, proved to be a calm and confident leader through the unfolding crisis. He shrugged off the more reactionary members of his council as reports of Scottish raids flooded in. He would not be drawn into the war in the north before he was ready to fight. Instead, he responded to Carrick's violations of the truce in kind. England's northern powerhouses like the Cliffords, Nevilles and Umfravilles were given free rein against the Scots. Henry Percy, 4th baron Percy and warden of the eastern march, was ordered to retake Berwick before the king arrived for the summer campaign. No town on either side of the border was safe.

Edward was more aggressive and creative when it came to dealing with the duke of Burgundy. He refused to treat with Burgundy to save England's crumbling economy and instead did an end run around the duke. Sir Michael de la Pole was sent to strike a new trade agreement with Middelburg, a port city in Zeeland, that would keep English goods moving into the Low Countries and beyond. The city had both collaborated with and competed against the great trade cities of Flanders over the past century, and it had a vested interest in keeping English goods moving. This put Middelburg's wealthy townsmen at odds with their lord's regent, as Albrecht I, duke of Bavaria-Straubing, wanted closer relations with Burgundy and France, and even had a double marriage between his and Burgundy's children in 1384. From Middelburg, de la Pole traveled to Arnhem to bring the house of Jülich into an alliance against Burgundy. The Jülichs had supported the English in the past and, as one of the greatest families in the Low Countries, they felt threatened by Burgundy's increasing dominance of the region.

As de la Pole moved through the Low Countries, Edward received an embassy from the city of Ghent, where a 1379 revolt had led to uprisings across the whole of Flanders before being beaten back by the French crown in 1382. Ghent was, by 1385, the final holdout of the near-revolution. Edward sent the city's ambassadors home with 300 archers and 100 men-at-arms at their backs.

The duke of Burgundy carefully followed England's moves in the Low Countries, but he did not overly concern himself with them. Burgundy was an old diplomatic hand and he knew when his opponent was bluffing. The movement of English fighters into Ghent was an unwelcome development, but just 400 men could not save the city in the long run. The alliance with the Jülichs was also unwelcome, but the dukes of Jülich, Guelders and Berg were in no position to move against Flanders before July, when the second army was set to sail for England. Burgundy believed that, once the French invasion was underway and England was reduced to ash, the Jülichs would be compelled to reconsider their alliance with England.

On 25 May, Jean de Vienne landed at Leith with around 1,600 fighting men, plus hundreds—perhaps as many as 1,000—more in support staff. He also landed with 50,000 livres (£8,333), which he deposited into the Scottish treasury. Most of this was spread around to the Scottish lords who had turned out to support the French, but the rest was given over to Robert II to keep him quiet while Carrick and the French managed an invasion through Robert's kingdom without his input.

English plan of attack

On 4 June, Edward summoned a great council at Reading Abbey. The choice of location demonstrated the seriousness with which he was considering the coming campaign. The abbey was situated just 15 miles southeast of Wallingford, which had become his mother's favorite residence in her old age. Edward acknowledged that he may die on campaign in Scotland and had wanted to see his mother once more before he did. It was the second meeting of the Lords that year, another sign that the king had no illusions regarding the dangers he faced, and a demonstration of his commitment to rule with their support.

Edward issued a feudal levy for the campaign, calling on the magnates to muster at Newcastle on 14 July. In this, he exercised an ancient right of kings that had been all but forgotten. His grandfather, Edward III, had issued the last such levy in 1327 ahead of the Weardale campaign, which Roger Mortimer led in all but name and ended in a humiliating defeat by the Scots. The summons called upon every knight in the realm who held land to perform service in defense of the realm or to pay a fine in lieu of service. Edward V refused pleas to forgo the fine. He was thus able to outsource the cost of the campaign to the nobility by pointing to Burgundy's boycott and the strain that it had put on the English crown as his reason for doing so.

Edward named his 12-year-old cousin, Edward of Norwich, guardian of the realm for the duration of the campaign. It was a purely ceremonial position meant to note the person inside the kingdom who was the highest in the line of succession during the king's time abroad. Actual power was vested in a council led by Simon Sudbury, archbishop of Canterbury. Sir Thomas Holland, the king's half-brother, was charged with the defense of the realm in the king's absence. Holland was a highly competent figure who had served in many minor commands, but this was a major task. He ordered positions along the coast to make any necessary repairs and every coastal community from Cornwall to Norfolk to set up coast guards and place warning beacons on hilltops. Holland himself took up residence at Dover Castle with 600 men and fast horses, hoping that from there he could respond to calls for help.

On 23 July, Edward reached Newcastle. The response to the king's summons was overwhelming, as more than 14,000 men turned out to fight, supported by many thousands more attendants, pages, and servants. The king's royal uncles had the largest retinues, as John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster, had roughly 3,000 men in his service while the dukes of Aumale and Gloucester had around 1,000 each. Gaunt's son, Sir Henry of Bolingbroke, had his own retinue in addition to his father's. Edward's brother, Sir Richard of Bordeaux, had the smallest retinue of the royal family, but he had neither a great estate nor a wealthy heiress to support him, as his uncles and cousin did. About 1,000 men came in the service of two royal cousins by marriage, Edmund Mortimer, 3rd earl of March, and Robert de Vere, 9th earl of Oxford. More than 300 came under Thomas Beauchamp, 12th earl of Warwick, whose retinue was the largest from outside the royal family.

Scottish invasion of England

On 8 July, Carrick and Vienne led the Franco-Scottish army south from Edinburgh. The truce was not set to expire for another week, but it was still a later start to the campaign than either had wanted. Weeks were wasted by arguments between their captains, who disagreed as to how they should make war on the English. The French wanted to target major walled towns and small castles, but the Scots feared being bogged down by a siege and exposed to attack by the English, preferring to ride hard and fast across the country to inflict maximum damage and grow rich from cattle rustling. A compromise was eventually settled upon and sealed in an agreement between Carrick and Vienne, but the delay irritated leaders in both camps and the men in their armies grew to resent one another.

The Franco-Scottish army numbered about 4,600 men, of which nearly two-thirds were Scots. Its roster was almost as spectacular as that of the English army at Newcastle. Nine of Robert II's sons were a part of the campaign. Carrick led the army. He was joined by his most powerful brother, Robert Stewart, earl of Fife, their legitimate half-brothers David Stewart, earl of Strathearn, and Walter Stewart, earl of Atholl, plus five bastard half-brothers. The two great lords of the marches, George Dunbar, 10th earl of Dunbar, and James Douglas, 2nd earl of Douglas, were there as well, along with John Dunbar, 1st earl of Moray, and Archibald Douglas, lord of Galloway.

Carrick and Vienne led their men across the Tweed in the hopes of taking Roxburgh Castle, but found it too well defended. They moved on to Wark on Tweed Castle, which the English had retaken since its capture and partial demolition by the Scots two years earlier. Animosities that had been birthed by the delay in Edinburgh flared up during debate over the value of the castle. The French insisted on taking the position, but the Scots declared it worthless and refused to help. The French captured the castle on their own, as the Scots continued east along the march and massacred stragglers who had not yet fled the area.

The Siege of Wark was a major breach of trust for the French, who did not try to hide their hostility toward the Scots when they returned to the area. French captains declared that the Scots were "savages" lacking decency and honor. Vienne was more diplomatic in his dealings with the Scots, but his letters back to Paris were filled with a number of similar sentiments. The Scots were indignant. Five of the seven earls who had set out from Edinburgh with the French quit the campaign in protest, leaving only Carrick and his powerful ally, the earl of Douglas, behind.

Carrick and Vienne moved further east to attack Cornhill Castle and Ford Castle, but the English then began to move north from Newcastle. The Franco-Scottish army, which now had fewer than 3,000 men, retreated west before moving south to attack Carlisle instead.

French invasion of England

On 17 July, Charles VI wed Isabeau of Bavaria at Amiens. At Sluys, some 15,000 men were waiting to set sail for England. An embarkation date for the French invasion was set for 1 August. The great men of the realm were to move from Amiens to Sluys after the wedding festivities and lead the greatest invasion of England since Louis the Lion in 1216. Instead, the invasion was canceled the day after the celebration.

Frans Ackerman and Pieter van den Bossche, the last remaining leaders of the once-great Revolt of Ghent, used the occasion of the king's wedding to launch a surprise attack on nearby Damme. Supported by Sir John Bourchier, who led the 400 Englishmen sent to Ghent earlier in the year, they found the city was practically undefended. The captain of Damme was away organizing materials for the invasion and the leaderless garrison was completely unprepared for an attack. The Anglo-Ghentian force slaughtered the would-be defenders and the local population.

The loss of Damme immediately upset French preparations for war. The city's position on the canal system cut Sluys off from Bruges, stopping the flow of food and materials needed to survive while on campaign. On 18 July, Burgundy ordered the men at Sluys to move to Damme and retake the city. The siege stretched into late August before the Anglo-Ghentians abandoned the city and fled back to Ghent in the dark of night. By then, the French had eaten through too much of their food supplies to consider launching an invasion of England. Despite dire warnings from Vienne regarding his men falling out with the Scots, the admiral's expeditionary army was on its own.

English invasion of Scotland

The Scots offered no resistance to the English. Robert II fled Edinburgh for the Highlands while the earls and other lords who'd quit the campaign in England dispersed to their own safe havens. What remained of the Franco-Scottish army slunk off toward the western march. Common Scots fled the English on their move north, taking everything of value with them. Edward marched the English on a six-mile front, destroying crops, homes, and whatever else they found. Even churches and monasteries were burned, the consequence of Scotland's obedience to the pope in Avignon.

Reaching Edinburgh without opposition on 11 August, Edward had the city razed to the ground. The defenders of the castle looked down helplessly as the royal palace burned. The king assembled a war council as Edinburgh was turned to ash. The lords could offer him no clear answer as to what he should attempt to do next. Edward had learned from the failure of his uncles Aumale and Gloucester in 1384 and ensured that the army was supplied by sea, meaning he could continue on campaign for weeks more if they remained close to the coast. A siege of Edinburgh Castle was considered, but the king's uncle, Gaunt, then recalled his disastrous experience besieging León on Lancaster's Crusade. He instead suggested moving north to cross the Forth. The English did not know the details of the French invasion plan, including their intended landing place, and news of Damme had not reached the army in Scotland. Gaunt thought the second French army may be intended for Scotland as well, and thus was suggesting they cross the Forth and put the Scottish coast to the torch all the way to the Firth of Tay so as to deny the French a port of entry. Gloucester disagreed, insisting that they move south to confront Carrick and Vienne, who were thought to be moving through Ettrick Forest. This drew sharp objections from the king's brother, Richard, who feared the Scots could be lying in wait in the forest.

According to the French chronicler Jean Froissart, Edward recalled the "Prophecy of the Six Kings" when choosing a course of action. It said that the sixth king that followed King John of England—i.e., Edward V—would be a cowardly mole whose line would be dispossessed of the crown. Among the forces that would bring down the sixth king was "a dragon from the north," which Edward believed symbolized the Scots. Edward, wanting to prove that he was not the coward that Merlin had foreseen, declared that he would go to meet Carrick and Vienne in battle, as Gloucester had suggested. He saw the strategic value of Gaunt's suggestion, though, and so decided to split the army.

The English army was divided three ways. Edward's uncles Gaunt and Aumale would lead the first division of about 4,000 men from Edinburgh to Sterling, destroy the town and round the Forth to lay waste to the whole coastline. The king's other uncle, Gloucester, would lead the second division of 4,000 down to Norham Castle, along with the earls of Arundel, March and Warwick and the marcher lords Neville and Percy. Together, they would sweep the marches from east to west and flush the French and Scots north. The king himself would lead the main army, about 6,000 strong, south through Ettrick Forest to attack the Scots or drive them east toward Gloucester's army.

The mission that Edward gave himself was the most dangerous of the three assignments by far. The fears that his brother, Richard, had voiced were not unfounded. English reports on the Franco-Scottish army's movements were sketchy at best, so it was certainly possible that Carrick and Vienne were luring the English into a trap. Ultimately, these fears were unfounded.

The French and Scots had crossed into Cumberland in mid August. Carrick and Vienne had agreed to make an attack on Carlisle before they arrived, but the French were again left to their own devices when the time came. The Scots made their way through Cumberland and into Westmorland, where Scottish raiders had not been seen in some time, promising rich booty for the Scots. The French launched their own attacks on Carlisle, but were twice repulsed with heavy casualties. The Scots later rejoined the French, but plans for a coordinated assault were abandoned when word arrived that Neville and Percy were approaching. Carrick and Vienne made a hasty retreat north, heading back the way they had come.

Battle of Arkinholm

On 7 September, the English and Franco-Scottish armies spotted one another near the village of Arkinholm in Dumfriesshire. Edward's men were hungry and tired. They had marched more than 70 miles through the hills and forest to cut off Carrick and Vienne's retreat north. It was hard terrain and moved the army away from the seaborne supply train, forcing them to survive on rations of salted meat and foraged food on their way.

Carrick and Vienne understood that they had been caught in a trap. Edward's army cut off their escape into the hills as Neville and Percy moved in from the east. Edward had twice as many men as the French and Scots, but the English were exhausted and the king was a green knight who had never fought a battle. French and Scottish captains agreed that their best course of action was to give battle, fearing that they would be overrun if Neville and Percy caught up to them and believing that the young king's inexperience could be his undoing.

The two armies arranged into battle formations. It was the first major battle between the English and either the French or Scots in many years. Edward, fearing that some overeager captain may break ranks and ruin the day, issued orders that any man who broke the line and survived would be hanged. In the end, it was the French who could not be controlled. Disagreements between the French and the Scots on battle tactics, and even between groups of Scots who wanted to organize traditional schiltrons and those who believed such a compact body of men would be easy targets for English archers, confused the men in the joint army. Either misunderstanding the plan or simply disregarding it, the French charged the English line before the Scots were ready. The disorderly French attack broke against the English line. Carrick, hoping to salvage the situation, ordered his men forward to support the French. The rush of Scots only added to the chaos, resulting in heavy casualties.

Edward ordered a counterattack, looking to crush his opponents before French or Scottish commanders had the opportunity to impose any sort of order. Sir Henry Percy, eldest son and heir of the baron Percy, cut his way through the French line and charged toward the Scots, personally clashing swords with Carrick. The earl of Douglas saw the battle was turning into a rout and ordered his men to retreat. Carrick was knocked from his horse in the mayhem that followed, breaking his knee. Englishmen began seizing French knights and taking them as prisoners. Most Scots fled, but Sir Thomas Erskine and Sir William Cunningham fought to defend their injured lord, Carrick, until he finally ordered them to lay down their swords and surrender. Around 500 French and Scottish men were killed, compared to fewer than 100 Englishmen.

Aftermath

Edward moved south from Arkinholm with his prisoners, which included Carrick, Vienne, and at least 250 others. He rested for a night at Carlisle, where the locals rejoiced at their change of fortune after having fended off Vienne just weeks earlier. Edward issued a summons for parliament to meet at York before making for Chester, imprisoning the heir to the Scottish throne far from the border.

Gaunt and Aumale devastated Scotland for more than a month after leaving Edinburgh in mid August. Their appearance north of the Forth caught many by surprise. It was the furthest that an English army had gone into Scotland in several decades. They returned to England on 16 September, having inflicted yet more destruction on Lothian as they returned south. Word of their kingly nephew's victory at Arkinholm and his summons for parliament likely reached the two dukes just as they returned to England.

The French and Scots were forced to suffer further humiliation before year's end. In mid September, a storm swept through the Channel as the great French armada at Sluys slowly dispersed, driving a dozen ships to shore near Calais. The English garrison there set upon the crews, taking some 500 men as prisoners and seizing their ships. Meanwhile, Carrick's allies organized a retaliatory campaign as English forces withdrew from Scotland. Some 200 Scots descended on Redesdale early in the morning of 4 October, but Sir Thomas Umfraville and his son, also named Thomas, led a spirited defense of the town, killing or capturing several dozen Scotsmen. Thomas the Younger was knighted by the king himself at parliament just weeks later.

On 27 October, parliament assembled at York. Edward was greeted with roars of approval from the Lords and Commons. He put Carrick and Vienne, his two highest-profile prisoners, on display. On his arm for the first time was his young wife, Giovanna of Naples, who had landed in England that summer, as Edward was crossing the border to Scotland. Swept up in the excitement of the king's victory, the Commons readily agreed to another grant of taxation to meet the threat of a possible French invasion in 1386.

The mood was far less celebratory when the Scottish parliament assembled on 8 November. It met at Scone as a result of the destruction of Edinburgh and Holyrood. The mood was sober. Carrick's lieutenancy of the realm had lasted less than a year and it had brought the greatest disaster upon the land since Edward III's Burnt Candlemas campaign of 1356. Many looked to Robert II's second son, Robert, earl of Fife, for leadership. Fife was no less ambitious than Carrick, and possibly moreso, but he had the good sense to reject calls for him to take up the mantle of lieutenant, not wanting to be associated with the unpopular decisions that would need to be made to clean up Carrick's mess. This led the aged Robert II, who was broadly unpopular for his appeasement of the English and his negligence in administering justice at home, to make the most unlikely comeback. Robert arranged for the French who had escaped capture at Arkinholm to return home before securing a six-month truce with England, which was set to run from New Years to 1 July 1386. Progress toward Carrick's release was slow, though, and the truce was soon extended until summer 1387. The marcher lords could hardly object to a pause in hostilities after Edward's punishing campaign.

Edward gladly welcomed Robert's offer of a truce, evidenced by the fact that it was negotiated in only a matter of weeks and put into force at the start of the new year. England had only narrowly avoided its own devastation at the hands of the French and Edward needed peace with the Scots to turn his attention to the threat he faced from across the Channel.

The French were undeterred by the failures of 1385. They believed that the loss at Arkinholm was the fault of the Scots, as Vienne's letters had predisposed them to the notion that their allies were simple brutes and brigands. They thought, as a result, that victory over the Scots had not required much skill on Edward's part, writing off his victory. The French likewise attributed the temporary loss of Damme to Ghent's rebel leaders, believing the English investment of arms too small to be significant. Such blatant disregard for England's achievements in 1385 left the French uncritical of themselves. As a result, they did not consider any strategic changes regarding the war with England, simply deferring invasion plans for a year.

One of the only areas in which French policy changed was in Flanders. The capture of Damme had exposed the risk that the rebels of Ghent posed, leading the duke of Burgundy to adopt a new, conciliatory approach in his dealing with them. Burgundy conceded to many of the city's demands for new rights and privileges, and even offered the rebels the protection of a royal pardon as a demonstration of his goodwill. The rebels, knowing that they could not hold out against the French forever and having been unimpressed that Edward sent them just 400 men under a knight of little renown, accepted the offer.

The alliance between France and Scotland was hugely strained by the failure of their joint campaign. The two countries remained allies on paper, but grew further apart than ever before. Their differences were not limited to matters of policy, as they had been in the 1370s. French knights who fought in Scotland painted a picture of a poor land full of backwards people. It became the conventional wisdom in Paris that the power of the Scots had been very seriously overestimated and that their inclusion in the 1385 invasion plan had only complicated matters. The French reevaluation of the Scots led to heated diplomatic exchanges when, in 1386, Robert II argued that the agreement that Carrick and Vienne had signed in Edinburgh had made Carrick a retainer of Charles VI, thus obligating the king of France to pay Carrick's ransom.

Impact

The 1385 English invasion of Scotland was much celebrated by contemporary English writers, but received only passing mentions in French sources. This reflects its relative importance on the war efforts of the two kingdoms. As historian Nigel Saul noted in his biography of Edward V, the English had achieved a major goal in relieving pressure on their northern border, but this "hardly affected the balance of power between England and France." The French had dominated the English during the long Anglo-Scottish truce, having reconquered most of Aquitaine, resubjugated Brittany, and dispossessed the king of Navarre of his lands in France in the 1370s and early 1380s. The French thus had no reason to believe that Scotland exiting the war again in 1386 would significantly impact their own war effort.

The invasion rewrote the politics of England and Scotland, though. The nascent peace party that had formed in the English Commons immediately disappeared while Scottish war hawks fell silent for a time. Marcher lords on both sides of the border remained hostile to one another, but outbreaks of violence became infrequent and, except for a major confrontation in 1388, were much smaller in scale.

The finances of the English crown were transformed at a stroke. Edward borrowed a substantial sum from his uncle, Gaunt, who had returned from Lancaster's Crusade flush with cash, to buy the rights to ransom nearly every one of the men captured at Arkinholm. This quickly put money in the pockets of the English who had taken prisoners in battle while positioning the crown to make a windfall by negotiating more than 200 ransoms. That a disproportionate number of those captured were French, who typically brought higher sums than Scottish captives, made the haul of prisoners especially lucrative. Vienne brought 100,000 francs (£16,667) to the English treasury on his own, owing to his position as admiral of France. Carrick, as heir to the throne of Scotland, was the greatest prize, though.

Negotiations over Carrick's ransom dominated Anglo-Scottish relations in the mid to late 1380s. Robert II had an extraordinarily weak hand in talks. The old king turned 70 when talks for his eldest son and heir's release began in spring 1386, putting enormous pressure on the Scots to get a deal quickly for fear that Robert would die with Carrick still in English custody. At the same time, though, the Scottish treasury was unable to meet the demands being made by England. This led Robert to assert that Carrick had fought on retainer for Charles VI in an attempt to put the financial burden of Carrick's release on the French. This was not well-received in Paris, but the French did eventually agree to send another installment of 50,000 livres (£8,333) to Robert II in order to avoid a more serious breakdown in Franco-Scottish relations. In 1389, his ransom was finally agreed for 60,000 marks (£40,000), plus the 32,000 marks (£21,333) still outstanding from David II's ransom.

The campaign also had a profound impact on the English nobility. It was a coming of age for a whole new generation of young men. Edward V, aged 20 at the time of the battle, was still technically a year shy of his majority, but had stepped into his own power. At his side at Arkinholm were Sir Henry of Bolingbroke and Sir Henry Percy, who would become two of the greatest heroes of Edward's generation, and many more. The speed with which Percy smashed through the French line and charged Carrick became the subject of a popular bard's song, earning Percy the nickname "Hotspur." In 1386, Edward established a new chivalric order for his "brothers in arms," the Order of the Bath, which was kept exclusively for men who had fought with the king in battle. Upon its founding, that included only those who had been at Arkinholm and the 1386 Battle of Écluse.

Last edited: