Introduction pt. 1

Made a Nation: America and the World after an alt-Trent Affair

“We may have our own opinions about slavery; we may be for or against the South, but there is no doubt that Jefferson Davis and the other leaders of the South have made an army; they are making, it appears, a navy; and they have made what is more difficult than either, they have made a nation.”

The outbreak of civil war in America was far from unnoticed in the capitals of the world’s great powers. In France, Emperor Napoleon III was intrigued at the at the possibilities for his country, and particularly for his ambition of a renewed French presence in the western hemisphere. In Prussia, the military and political leadership were not slow to appreciate the importance history’s first industrial war, and to seek to understand the implications for the future development of warfare.

It was, however, the perception of the outbreak of war in Great Britain that was the most consequential to the way history would unfold. The British leadership had two main overlapping and conflicting impulses towards the United States. On the one hand, there was the legacy of the two previous Anglo-American conflicts of the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. This was embodied by a mix of disdain towards American culture and society, along with suspicion of the United States as a possible future threat to Britain’s global pre-eminence. This disdain and suspicion had been exemplified by the reaction to the contribution of the United States to the Great Exhibition a decade earlier, which was simultaneously a dismissiveness of its lack of grandeur with a more sober reflection upon America’s growing industriousness.

On the other hand, there was a sincere and widespread revulsion towards the institution of slavery present in all segments of British society. Whereas Harriet Beecher Stowe’s famous anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin sold 300,000 copies in the United States, it sold over a million in Britain and every respectable household was said to have a copy. Frederick Douglass was well received throughout Britain and Ireland during his 1845-47 speaking tour to promote the abolitionist cause.

Prime Minister Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston.

The Prime Minister at the time, Lord Palmerston, was among the opponents of slavery. Nevertheless, he was perhaps more a representative of the first impulse of disdain towards the United States. Palmerston had a suspicion of revolutionary politics and the exercise of power by society's lower echelons. Furthermore, Palmerston could be considered as a sort of nationalist. His unrelenting and aggressive defence of Britain’s interests certainly made him fairly unpopular in Europe, to the point where the Prussians had a contemporary saying that “if the Devil has a son, surely he must be Palmerston.”

Palmerston’s outlook would be instrumental in the ultimate outbreak of war, but it must be noted that in the years before the war some of his anti-American feeling could actually be attributed to the control of the American federal government by southern slaveowners. In 1841, he remarked upon his efforts to secure a treaty which would allow the Royal Navy to search merchant ships of the other great powers potentially engaged in slave trading that “If we succeed, we shall have enlisted in this league every state in Christendom which has a flag that sails upon the ocean, with the single exception of the United States.”

It is perhaps partly because Palmerston seemed to embody both of these main strains of thought towards the outbreak of war that for almost the first 2 years of the conflict that Britain maintained its neutrality, despite tensions with the Lincoln administration over the granting of belligerency status to the Confederacy. This was contrary to the expectations of practically all southerners, whose overestimation of Britain’s dependence upon their cotton is best represented by a speech given by Texas Senator Louis Wigfall wherein he stated that “Cotton is King” and that even Queen Victoria would have to “bend the knee in fealty and acknowledge the allegiance to that monarch.”

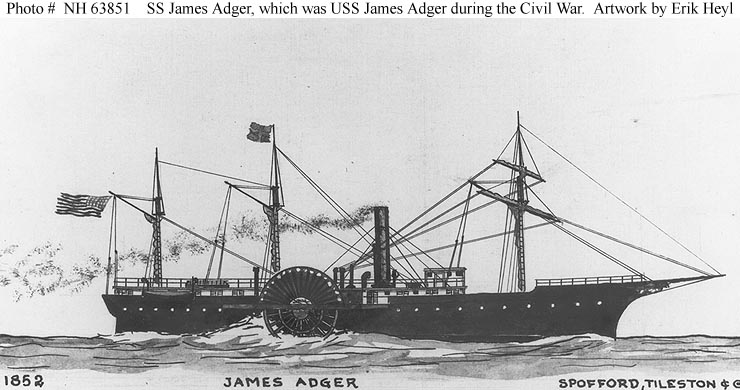

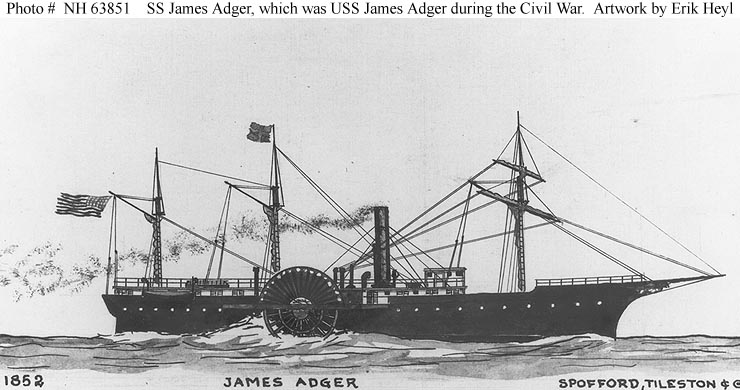

Fortunately for the South, Britain’s neutrality was fragile, and a combination of misunderstanding and recklessness would derail it towards the end of 1861. Frustrated with the ongoing blockade of their coasts by the US Navy, Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed Senators James Mason and John Slidell as commissioners to petition the British government for recognition and help. The US Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles, sought to capture the two commissioners and to this end dispatched 3 warships to search for them. One of these was the USS James Adger, captained by Henry Sanford. It was Sanford’s actions that would ultimately precipitate the crisis which brought Britain into what had previously been a civil war.

USS James Adger, the ship which precipitated Britain's entry into what had until then been a civil war

The James Adger was forced to limp into Southampton after a particular harsh storm off the cost of Ireland. The vessel’s unexpected arrival coincided with the planned departure from London dockyards of the Gladiator, a Confederate blockade runner. It was at this point that Sanford concocted a scheme to seize the cargo and crew of Gladiator and depart before the British authorities could react. Sanford considered consulting the US Minister Charles Adams about his plan, but ultimately decided to proceed on his own initiative. [POD] On the 5th November the USS James Adger ran the Gladiator aground on a Thames mudbank, seizing its cargo and crew before absconding out to sea.

It did not take long for the British authorities to react. Vice Admiral Robert Small, commander of the Royal Navy’s Channel Squadron was ordered to give chase to the James Adger, and he duly caught up to and captured the vessel off the coast of Devon. Captain Sanford was treated amicably, but he and his crew were nevertheless detained. Sandford’s actions universally outraged public opinion in Britain, and it was regarded by all as an egregious insult to Britain’s sovereignty and dignity to commit an act of naval warfare in the estuary of the Thames itself. Sanford’s action inaugurated what became known to history as the Adger Affair.

The Cabinet unanimously agreed that a stern response was necessary. While the Chancellor Gladstone argued that any letter to President Lincoln ought not to be so strong as to leave him no option but war, the Foreign Secretary John Russell nevertheless drafted a very strongly worded response. It was at this point that a gravely ill Prince Albert intervened, attempting in a final act of service to his adopted country to moderate the language of the missive in an attempt to avert war. Unfortunately for those wishing to avoid an Anglo-American conflagration, it was at this very point that London received word of yet another incident.

Not long after Henry Sanford had been committing his folly, the two Confederate commissioners had boarded the British mail packet the RMS Trent in Havana in order to travel to Britain. The USS San Jacinto, commanded by Charles Wilkes, boarded the Trent and detained the commissioners. The boarding was regarded by the British as a violation of their flag and the timing of word of the incident reaching Britain was perfectly timed to derail Prince Albert’s peace-making efforts. The Cabinet came down firmly on the side of a harsh ultimatum demanding an apology and restitution for both incidents, and the Prince acquiesced. Palmerston at this point seems to have regarded war as inevitable.

In the North, the reaction to these events was quite different. The incident involving the James Adger was not yet known, and Lincoln and the general public for some weeks knew only of the seizure of the envoys by Captain Wilkes. The press and the public viewed Wilkes as a national hero, his actions being regarded as a much needed moral victory. The New York Times reported that “We do not believe the American heart ever thrilled with more genuine delight than it did yesterday at the intelligence of the capture of Messrs. Slidell and Mason.” The simultaneous news of the incident with the James Adger and the British demand for restitution dramatically escalated tensions. The press inclined toward viewing Sanford as equally a hero as Wilkes, and many Americans rejoiced in the supposed humiliation of their old enemy. Lincoln and his Cabinet, however, were very much focused on Russell’s ultimatum upon delivery by the British Minister to the United States Lord Lyons.

Besides Secretary of State William Seward, who despite previous bluster fully understood the dire implication of war while the South remained in rebellion, no other member of the Cabinet supported accepting the demand for an apology and restitution for both incidents. The accusatory tone of the missive was also regarded with outrage by many, and there was great reluctance to be conciliatory in light of the sharp anti-British turn of public opinion. Lincoln was forced to reject the demands, and just a few days before the turn of the year Lord Lyons and the rest of the British legation departed Washington for Halifax, Nova Scotia. At this point, war was indeed inevitable.

The consequences for the Union would be disastrous. The supremacy of the Royal Navy effectively reversed the situation at sea. Far from being able to blockade the South, now the North was itself under blockade. The implication of this was a sudden cut-off of the international trade upon which the smooth running of the war effort depended, a particularly important example being the critical military supply of saltpetre. The British government had wisely ordered a large shipment of this suspended at the beginning of the crisis. The outbreak of war was also a tremendous morale boost throughout a South that had begun to seriously struggle under the weight of war and blockade, with every soldier and citizen understanding the importance of these developments.

Despite some success in the western theatre and in the invasion of Upper Canada, a series of key defeats as Britain brought the full force of its global power to bear in North America slowly eroded public support for the war effort and for Lincoln’s administration over the course of 1862-63. By early 1864, the Army of Northern Virginia under the command of General Joseph E. Johnston had overrun Washington D.C. and forced the relocation of the government to Philadelphia. Much of northern Maine was under British control, an uprising in Baltimore was put down only with severe brutality and the force of the Royal Navy had been felt severely on the still sparsely populated west coast.

That the war continued until the 1864 presidential election is largely due to the assassination of Abraham Lincoln by pro-Confederate Marylander John Wilkes Booth in March of that year. The result of this was the accession of Radical Republican Hannibal Hamlin to the presidency, with the outrage of the assassination allowing him to rally his supporters enough to continue the war for the time being.

Hamlin’s desire to continue the war was, however, subject to the results of the presidential election in November that year. While he was able to secure the nomination of the Republican Party with Major General Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts as his running mate, his chances of victory were slim. The Republican Party was widely perceived as having led the country disastrously, and a desire for peace was widespread.

The Democratic presidential nominee was Clement Vallandigham, a resolute believer in white supremacy, an opponent of the war effort and a longstanding critic of abolitionism. Vallandigham had been convicted in an Army court martial for opposing the war, and subsequently been removed from office and imprisoned. Despite this, he won election as Governor of Ohio in 1863, which was regarded nationally as a sign of growing disillusionment with the war. Governor Vallandigham, with railway industrialist George W. Cass of Pennsylvania as his running mate, would win the 1864 presidential election fairly decisively on a platform supporting “peace with honour.”

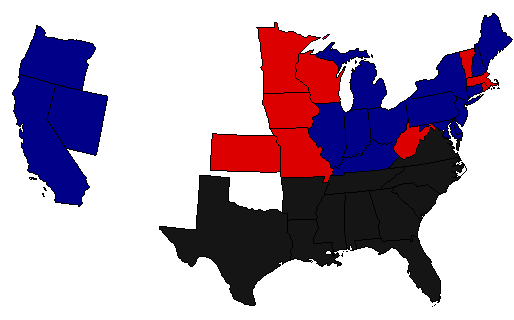

Clement L. Vallandigham (D-OH)/George W. Cass (D-PA) – 2,387,389 – 159 electoral votes

Hannibal Hamlin (R-ME)/Benjamin F. Butler (R-MA) – 1,669,376 – 60 electoral votes

“We may have our own opinions about slavery; we may be for or against the South, but there is no doubt that Jefferson Davis and the other leaders of the South have made an army; they are making, it appears, a navy; and they have made what is more difficult than either, they have made a nation.”

William Ewart Gladstone

The outbreak of civil war in America was far from unnoticed in the capitals of the world’s great powers. In France, Emperor Napoleon III was intrigued at the at the possibilities for his country, and particularly for his ambition of a renewed French presence in the western hemisphere. In Prussia, the military and political leadership were not slow to appreciate the importance history’s first industrial war, and to seek to understand the implications for the future development of warfare.

It was, however, the perception of the outbreak of war in Great Britain that was the most consequential to the way history would unfold. The British leadership had two main overlapping and conflicting impulses towards the United States. On the one hand, there was the legacy of the two previous Anglo-American conflicts of the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. This was embodied by a mix of disdain towards American culture and society, along with suspicion of the United States as a possible future threat to Britain’s global pre-eminence. This disdain and suspicion had been exemplified by the reaction to the contribution of the United States to the Great Exhibition a decade earlier, which was simultaneously a dismissiveness of its lack of grandeur with a more sober reflection upon America’s growing industriousness.

On the other hand, there was a sincere and widespread revulsion towards the institution of slavery present in all segments of British society. Whereas Harriet Beecher Stowe’s famous anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin sold 300,000 copies in the United States, it sold over a million in Britain and every respectable household was said to have a copy. Frederick Douglass was well received throughout Britain and Ireland during his 1845-47 speaking tour to promote the abolitionist cause.

Prime Minister Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston.

The Prime Minister at the time, Lord Palmerston, was among the opponents of slavery. Nevertheless, he was perhaps more a representative of the first impulse of disdain towards the United States. Palmerston had a suspicion of revolutionary politics and the exercise of power by society's lower echelons. Furthermore, Palmerston could be considered as a sort of nationalist. His unrelenting and aggressive defence of Britain’s interests certainly made him fairly unpopular in Europe, to the point where the Prussians had a contemporary saying that “if the Devil has a son, surely he must be Palmerston.”

Palmerston’s outlook would be instrumental in the ultimate outbreak of war, but it must be noted that in the years before the war some of his anti-American feeling could actually be attributed to the control of the American federal government by southern slaveowners. In 1841, he remarked upon his efforts to secure a treaty which would allow the Royal Navy to search merchant ships of the other great powers potentially engaged in slave trading that “If we succeed, we shall have enlisted in this league every state in Christendom which has a flag that sails upon the ocean, with the single exception of the United States.”

It is perhaps partly because Palmerston seemed to embody both of these main strains of thought towards the outbreak of war that for almost the first 2 years of the conflict that Britain maintained its neutrality, despite tensions with the Lincoln administration over the granting of belligerency status to the Confederacy. This was contrary to the expectations of practically all southerners, whose overestimation of Britain’s dependence upon their cotton is best represented by a speech given by Texas Senator Louis Wigfall wherein he stated that “Cotton is King” and that even Queen Victoria would have to “bend the knee in fealty and acknowledge the allegiance to that monarch.”

Fortunately for the South, Britain’s neutrality was fragile, and a combination of misunderstanding and recklessness would derail it towards the end of 1861. Frustrated with the ongoing blockade of their coasts by the US Navy, Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed Senators James Mason and John Slidell as commissioners to petition the British government for recognition and help. The US Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles, sought to capture the two commissioners and to this end dispatched 3 warships to search for them. One of these was the USS James Adger, captained by Henry Sanford. It was Sanford’s actions that would ultimately precipitate the crisis which brought Britain into what had previously been a civil war.

USS James Adger, the ship which precipitated Britain's entry into what had until then been a civil war

The James Adger was forced to limp into Southampton after a particular harsh storm off the cost of Ireland. The vessel’s unexpected arrival coincided with the planned departure from London dockyards of the Gladiator, a Confederate blockade runner. It was at this point that Sanford concocted a scheme to seize the cargo and crew of Gladiator and depart before the British authorities could react. Sanford considered consulting the US Minister Charles Adams about his plan, but ultimately decided to proceed on his own initiative. [POD] On the 5th November the USS James Adger ran the Gladiator aground on a Thames mudbank, seizing its cargo and crew before absconding out to sea.

It did not take long for the British authorities to react. Vice Admiral Robert Small, commander of the Royal Navy’s Channel Squadron was ordered to give chase to the James Adger, and he duly caught up to and captured the vessel off the coast of Devon. Captain Sanford was treated amicably, but he and his crew were nevertheless detained. Sandford’s actions universally outraged public opinion in Britain, and it was regarded by all as an egregious insult to Britain’s sovereignty and dignity to commit an act of naval warfare in the estuary of the Thames itself. Sanford’s action inaugurated what became known to history as the Adger Affair.

The Cabinet unanimously agreed that a stern response was necessary. While the Chancellor Gladstone argued that any letter to President Lincoln ought not to be so strong as to leave him no option but war, the Foreign Secretary John Russell nevertheless drafted a very strongly worded response. It was at this point that a gravely ill Prince Albert intervened, attempting in a final act of service to his adopted country to moderate the language of the missive in an attempt to avert war. Unfortunately for those wishing to avoid an Anglo-American conflagration, it was at this very point that London received word of yet another incident.

Not long after Henry Sanford had been committing his folly, the two Confederate commissioners had boarded the British mail packet the RMS Trent in Havana in order to travel to Britain. The USS San Jacinto, commanded by Charles Wilkes, boarded the Trent and detained the commissioners. The boarding was regarded by the British as a violation of their flag and the timing of word of the incident reaching Britain was perfectly timed to derail Prince Albert’s peace-making efforts. The Cabinet came down firmly on the side of a harsh ultimatum demanding an apology and restitution for both incidents, and the Prince acquiesced. Palmerston at this point seems to have regarded war as inevitable.

In the North, the reaction to these events was quite different. The incident involving the James Adger was not yet known, and Lincoln and the general public for some weeks knew only of the seizure of the envoys by Captain Wilkes. The press and the public viewed Wilkes as a national hero, his actions being regarded as a much needed moral victory. The New York Times reported that “We do not believe the American heart ever thrilled with more genuine delight than it did yesterday at the intelligence of the capture of Messrs. Slidell and Mason.” The simultaneous news of the incident with the James Adger and the British demand for restitution dramatically escalated tensions. The press inclined toward viewing Sanford as equally a hero as Wilkes, and many Americans rejoiced in the supposed humiliation of their old enemy. Lincoln and his Cabinet, however, were very much focused on Russell’s ultimatum upon delivery by the British Minister to the United States Lord Lyons.

Besides Secretary of State William Seward, who despite previous bluster fully understood the dire implication of war while the South remained in rebellion, no other member of the Cabinet supported accepting the demand for an apology and restitution for both incidents. The accusatory tone of the missive was also regarded with outrage by many, and there was great reluctance to be conciliatory in light of the sharp anti-British turn of public opinion. Lincoln was forced to reject the demands, and just a few days before the turn of the year Lord Lyons and the rest of the British legation departed Washington for Halifax, Nova Scotia. At this point, war was indeed inevitable.

The consequences for the Union would be disastrous. The supremacy of the Royal Navy effectively reversed the situation at sea. Far from being able to blockade the South, now the North was itself under blockade. The implication of this was a sudden cut-off of the international trade upon which the smooth running of the war effort depended, a particularly important example being the critical military supply of saltpetre. The British government had wisely ordered a large shipment of this suspended at the beginning of the crisis. The outbreak of war was also a tremendous morale boost throughout a South that had begun to seriously struggle under the weight of war and blockade, with every soldier and citizen understanding the importance of these developments.

Despite some success in the western theatre and in the invasion of Upper Canada, a series of key defeats as Britain brought the full force of its global power to bear in North America slowly eroded public support for the war effort and for Lincoln’s administration over the course of 1862-63. By early 1864, the Army of Northern Virginia under the command of General Joseph E. Johnston had overrun Washington D.C. and forced the relocation of the government to Philadelphia. Much of northern Maine was under British control, an uprising in Baltimore was put down only with severe brutality and the force of the Royal Navy had been felt severely on the still sparsely populated west coast.

That the war continued until the 1864 presidential election is largely due to the assassination of Abraham Lincoln by pro-Confederate Marylander John Wilkes Booth in March of that year. The result of this was the accession of Radical Republican Hannibal Hamlin to the presidency, with the outrage of the assassination allowing him to rally his supporters enough to continue the war for the time being.

Hamlin’s desire to continue the war was, however, subject to the results of the presidential election in November that year. While he was able to secure the nomination of the Republican Party with Major General Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts as his running mate, his chances of victory were slim. The Republican Party was widely perceived as having led the country disastrously, and a desire for peace was widespread.

The Democratic presidential nominee was Clement Vallandigham, a resolute believer in white supremacy, an opponent of the war effort and a longstanding critic of abolitionism. Vallandigham had been convicted in an Army court martial for opposing the war, and subsequently been removed from office and imprisoned. Despite this, he won election as Governor of Ohio in 1863, which was regarded nationally as a sign of growing disillusionment with the war. Governor Vallandigham, with railway industrialist George W. Cass of Pennsylvania as his running mate, would win the 1864 presidential election fairly decisively on a platform supporting “peace with honour.”

Clement L. Vallandigham (D-OH)/George W. Cass (D-PA) – 2,387,389 – 159 electoral votes

Hannibal Hamlin (R-ME)/Benjamin F. Butler (R-MA) – 1,669,376 – 60 electoral votes

Last edited: