Aside from the Global Warming Reduction Acts, the 2004 Buenos Aires Climate Agreement, and the 2005 Montreal Accord–finalizing the long Oslo process and giving the Palestinian people a state–Gore’s most significant legacy was likely the appointment of Barack Obama as the first Black American Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. This put liberals in charge of all three branches of government for the first time since the 1960s. The charismatic Obama had worked in all three branches of government: he had been a state senator and then Congressman from Illinois before serving in Gore’s Justice Department as Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights. There were some within the Democratic Party who believed that the soft-spoken Congressman could even be the first Black President of the United States, and that Gore’s appointment wasted such an opportunity to the detriment of the party’s interests.

While merit-based, as Obama had been a constitutional scholar before his legislative career began, Gore’s appointment of Obama was also an attempt to manage a multiracial political coalition increasingly strained by the ongoing war in Sudan. After 9/11, the people of the Middle East were terrified about becoming collateral damage via the wrath of the world’s sole remaining power. President Gore called “to root out those who coddle terrorists, and the tyranny that breeds such extremists.” Although there were elements within the Gore Administration that wanted to invade other countries in the wake of 9/11, Gore had continued Clinton-era light-touch counterrorism policies (if at a larger scale) until the Sudanese intervention. But, in the months after the “Mission Accomplished” banner was waved in 2004, Sudan’s fragile peace began to crumble, and the withdrawal of U.S. troops was halted and then reversed. The blodshed of the 2005 Ramadan attacks in Cairo, Alexandria, and the resorts of the Sinai Peninsula, for which al-Qaeda successor groups claimed credit, rocked the world and saw Egypt quietly threaten to withdraw its peacekeeping forces unless the American presence was redoubled, which Gore obliged. As the American military presence increased, and U.S. troops fought bloody engagements in Sudan, Chad, and southern Libya to suppress Islamist insurgency and prop up an increasingly authoritarian and dysfunctional coalition government in Khartoum with no end in sight, opposition to the war swelled. Where Gore had once been greeted as a savior in liberal jurisdictions and European capitals, he was now haunted by protest chants–“Gory Gore, We Want No War!”

Opposition to the war in Sudan along with Gore’s other “globalist” policies became a major engine for Reform’s growth. In the 2004 election, a plurality of Muslim Americans voted for Reform nominee Wilder, with traditionally conservative-leaning Muslim voters alienated from Gore’s cultural liberalism and Middle East policies, and from the Republican turn to Christian nationalism. While President Gore rhetorically discouraged Islamophobic and anti-Arab racism in the wake of 9/11, actual policy was a different matter: the federal government adopted intensive surveillance policies targeting those communities, with the FBI notoriously wiretapping mosques and entrapping young, troubled Muslim-American youth into “terror plots” largely conceived by FBI handlers. Yet, the Republican Party criticized these policies for not being harsh enough, driving Muslims and anti war activists to Reform.

The first evidence of this sweep came with the 2005 New York City mayoral election, where incumbent Democratic Mayor Mark J. Green was defeated in a huge upset by Reform Party candidate and former City Councilman Sal Albanese, who built an unlikely coalition of outer-borough Giuliani voters, Muslim and Arab New Yorkers, left-wing activists, and unions angered by Green’s hard bargaining and imperious attitude. Vice President Lieberman’s reputation for Muslim-baiting after 9/11 ensured the constituency would be up for grabs in the 2008 presidential election. Albanese’s triumph built on the momentum of Governor Golisano’s statewide win for Reform in 2002 but also on the surprise win of Green Party nominee Matt Gonzalez in the 2003 San Francisco mayor’s race.

2006 proved to be a landmark year for Reform: the Democrats had hit 14 consecutive years in the White House, and voters were ready for a change, yet the Republican Party remained mired in infighting between hardline Christian conservatives and emerging moderate challengers. This was an opportunity Reform claimed. In California, which had adopted a “fusion voting” system similar to New York’s by ballot initiative during the 2004 elections, Contra Costa County Supervisor Peter Camejo was elected Governor on a tripartisan Reform-Green-Peace and Freedom Party ticket. Camejo defeated a weak Republican nominee in Bill Simon and Democratic Congressman Bob Filner, who was favored until the final weeks of the race, when he was accused of multiple incidents of sexual harassment and groping. Camejo outright won Latino voters, with Univision providing valuable coverage to the socialist organizer’s run, and endorsements from Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (or “AMLO”) and Democratic primary loser and former Lieutenant Governor Cruz Bustamante likely proving decisive in his narrow victory. Simultaneously, Mexican American businessman Roque “Rocky” de la Fuente won California’s 49th District, marking the first time Reform won a seat in the House of Representatives, meaning that for the first time in a generation, three parties were represented in the new Republican-controlled Congress. Running a protectionist anti-immigrant campaign in English while advocating a more nuanced position in Spanish, the contradictions of Congressman de la Fuente only lasted one term, but he showed that it was possible for Reform to break through in the House, rather than just in local offices too minor for anyone to care about or statewide offices big enough for voter discontent to throw them off party line.

With a Reform-led coalition gaining control of the governorship in the United States’ most populous and culturally influential state, Reform was ready to genuinely contest the 2008 election as the true opposition party, the only one uncorrupted by power politics. Yet, Reform’s ideological incoherence and flirtation with anti-immigrant politics continued. Even while Reform elected Latinos in California, it supported harsh anti-immigrant and anti-Latino politicians elsewhere. Reform candidate and former Republican Congressman Tom Tancredo finally won the Governor’s office on a populist anti-immigrant campaign in Colorado. Meanwhile, after Hurricane Katrina, Louisiana voters voiced their discontent with both political parties by unseating Democratic Governor Kathleen Blanco and returning Buddy Roemer, a Democrat-turned-Republican-turned Reformer, to the Governor’s mansion.

The first inklings that the 2008 election would be tumultuous came in the form of an unusual spike in mortgage delinquencies in the fourth quarter of 2006. But what began as a slowdown in the property market slowly–then quickly–metastasized into a full-blown economic crisis. President Gore blamed greedy financiers and high oil prices, Republicans blamed economic mismanagement and Gore’s environmental policies, and neither sought to blame the true culprit: years of bipartisan financial deregulation. But Reformers identified it, and private polling of a possible general election found a generic Reform candidate in the lead for the first time ever. This scared many prospective challengers away from the Democratic side in particular, leaving widely disliked Vice President Joe Lieberman as the presumptive nominee.

In the leadup to the 2008 primary, Camejo and Ventura were seen as the two leading candidates for the presidential nomination. But Ventura alienated many Americans by suggesting President Gore may have deliberately allowed the 9/11 attacks to occur, a position for which he was excoriated by leaders of all three parties. Camejo, competing with Tancredo and a herd of also-rans, swept Reform’s primaries. He did so, despite rampant Red-baiting, with the aid of endorsements from Sal Albanese and Tom Golisano, who thought that Camejo was more reasonable than his sometimes-fiery rhetoric and that a left-wing outsider would be a potent candidate for an electorate in the midst of a financial crisis. Camejo was also helped by the fact that his record as an executive showed he could work with Democrats to pursue incremental reforms rather than self-immolate or try to rule as a dictator. Signs of Reform’s maturity were evident, as when Golisano was asked how he could support and campaign for a communist, he answered with a shrug and what became an ironically potent slogan for the Camejo campaign: “Nobody’s perfect, but Pete’s an honest guy.”

Meanwhile, in the Democratic primary, Vice President Lieberman was challenged in the primary by freshman Senator Bernie Sanders, an independent democratic socialist who caucused with the Democrats but had consistently refused to join them. After 16 years of the Republicans attacking “Clinton-Gore socialism,” the openly democratic socialist’s campaign caused much hand-wringing from the party establishment, particularly after Sanders won the Iowa caucuses, followed by a crushing victory in New Hampshire’s primary. Sanders’ campaign echoed Camejo’s, as while they used different buzzwords, both focused their fire on the FTAA, immigration reform, and the banking sector. Yet, Camejo’s populism was multilingual in English, Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese, Tagalog, Korean, and Vietnamese, while Sanders, focusing on white voters in the early primary states, ran out of steam as he hit Super Tuesday, although the two candidates fought a brutal slog until the Democratic National Convention. Yet, Sanders and Lieberman both competed to win over an electorate that had taken an anti-immigrant turn, something which would ultimately drive many Latino, Muslim, and Asian Americans to support Reform. Lieberman, conservative to his bones, selected Georgia Senator Max Cleland as his running mate, promising a campaign focused on national unity and defense in frightening times.

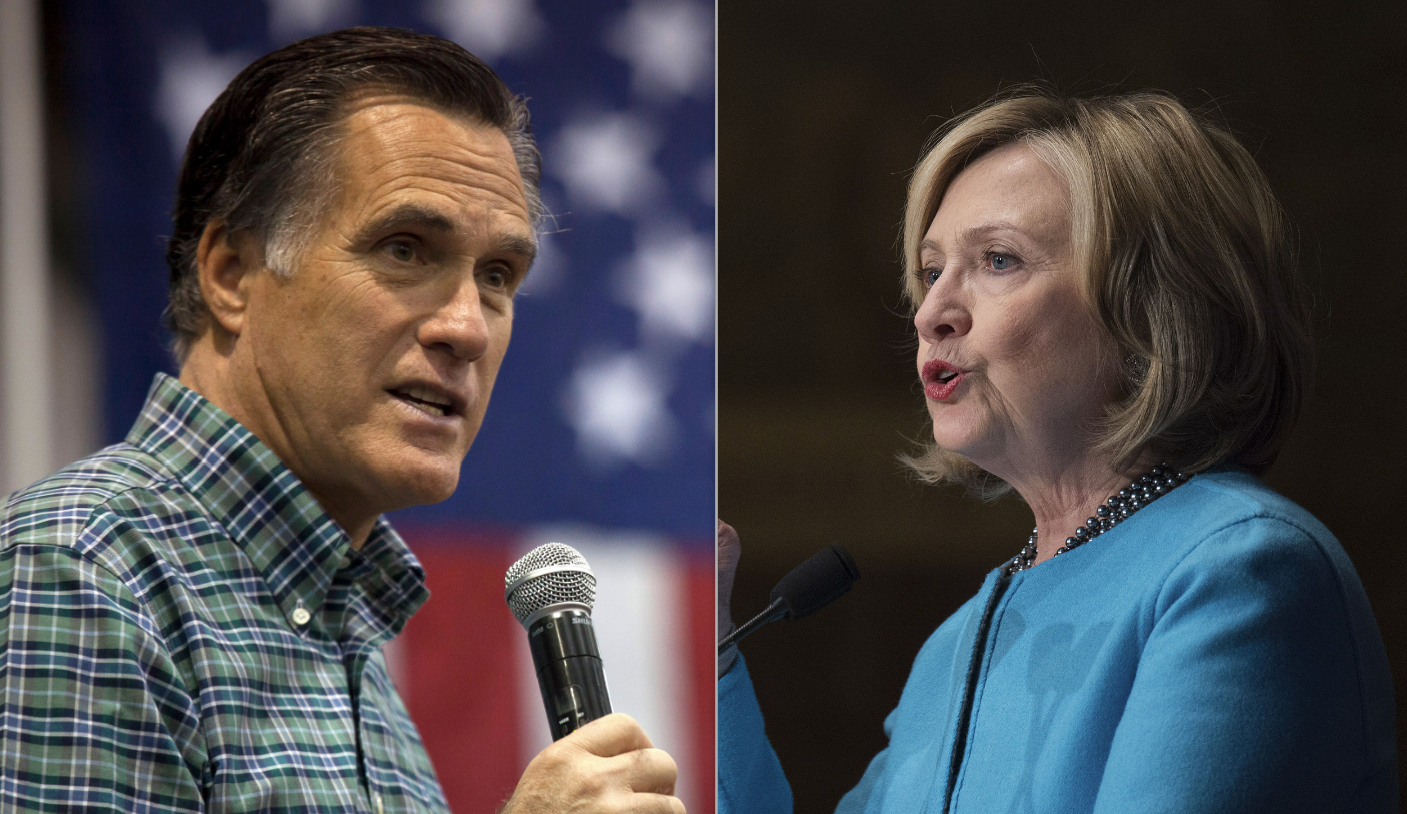

Meanwhile, the GOP nomination was wide open for the taking in 2008, with candidates adapting to more populist times. The top candidates were thought to be former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, former governor Jeb Bush of Florida, and Gary Johnson of New Mexico, an outsider. Senator George Allen of Virginia, and former Secretary of Defense John McCain also ran, as did former Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee. Yet, this time, the conservatives were divided and the Republican Party’s moderates had united behind the patrician and popular Massachusetts Governor, who promised a “Grand New Party” that could erase old national divides and win again. With Virginia Senator George Allen and former Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee splitting Southern evangelicals, Romney was able to triumph by winning pluralities in many states on Super Tuesday. Romney selected South Carolina Governor Mark Sanford as his running mate, a well-liked figure throughout the party who provided some Southern evangelical representation.

Heading into the general election, the Reform Party looked poised for possible victory. Seeking party unity in the face of Tancredo’s flirtation with an independent run and 2004 vice presidential nominee Clint Eastwood’s endorsement of Romney, Camejo had selected long-time Reformer Jesse Ventura as his running mate, with Ventura undergoing an apology tour for his “dumb-as-crap” 9/11 comments, as he memorably put it during one interview with CNBC. After receiving an endorsement from Sanders, the Camejo/Ventura ticket emerged from the Reform convention in San Diego with their poll numbers hitting as high as 40 percent of the vote.

Then the unthinkable occurred. While Camejo had previously suffered from lymphoma, he was in remission by the start of his presidential campaign. With a busy campaign schedule, the California Governor had been unable to monitor his condition adequately. On August 5, 2008, Camejo collapsed at a campaign event and was rushed to hospital. Within three days, he was dead, and his party and movement was adrift. He was succeeded by Lieutenant Governor Jackie Speier in California, who spoke at his nationally televised funeral. Per Reform Party bylaws, Camejo’s death led to an emergency convention, which duly selected Jesse Ventura. Many in Camejo’s campaign wanted to draft Senator Bernie Sanders or San Francisco Mayor Matt Gonzalez to head up the ticket, but couldnt prevail over Ventura’s long commitment to the party. While Ventura initially preferred former Connecticut Governor and longtime Lieberman rival Lowell Weicker as his running mate, seeking party unity, Ventura ultimately selected Gonzalez. Rocky de la Fuente, ever-mercurial, endorsed Romney over Ventura out of spite, and briefly starred in a special Telemundo miniseries entitled “Junto con Reforma, Junto con Romney” before leading Reform for Romney.

The closing months of the campaign were dominated by foreign policy crises. The U.S. financial crisis had rippled outward, causing economic turmoil and political unrest. Powered by a sudden spike in food prices, a wave of uprisings unsettled the Middle East. It began in the Republic of Palestine, where President Mahmoud Abbas–who had inherited his position from Yasser Arafat and had never won an election of his own–resigned after a disputed election and the jailing of opposition leader and later President Marwan Barghouti. Protests soon spread to Lebanon, where protests against the longtime Syrian occupation faced down tanks, and to Sudan, where protestors in Khartoum demanded the end of the American military occupation and a new government. Syria itself soon faced mass demonstrations in Damascus and Aleppo, and neophyte President Bashar al-Assad vacillated between appeasing the protesters by releasing political prisoners and restoring liberal reforms from his first days as president and cracking down. In October, Tunisians toppled President Ben Ali, while in Egypt, police and military units were met with barricades, Molotov cocktails, and chants of “bread and freedom” in Cairo’s slums. The the so-called Arab Spring was amplified by sympathetic global coverage from Qatari outlet Al-Jazeera, and turbocharged the growth of Web 2.0 social networks MySpace, YouTube, and a months-old website called Twitter, which began to advertise itself as “the global group chat.”

Feeling the revolutionary fervor of the moment, the Gore Administration initially gave rhetorical support to protestors’ democratic demands and announced that it would accelerate its planned withdrawal from Sudan. Romney condemned Gore’s policy as conceding American leadership and abandoning key U.S. allies, something which Vice President Lieberman–a notoriously hawkish advisor who had supported invading seven countries in five years in addition to Afghanistan after the 9/11 attacks–agreed with him. Lieberman went so far as to promise that he would support a humanitarian intervention in Iraq, where Saddam Hussein had met the initial wave of protests with mass murder. In response, Gonzalez acerbically called Joe Lieberman “Genocide Joe,” condemning the hypocrisy of his support of the Bahraini and Egyptian governments’ brutal crackdown on dissent while supporting intervention against Saddam Hussein for the same offenses.

With Iraq spiraling out of control, Gore resisted a full-scale intervention, but responded with renewed airstrikes, recognition of the Iraqi National Coalition (chaired by Ahmed Chalabi) as the legitimate government-in-waiting of Iraq, and provided support for an emerging insurgency inside the country. Controversially, this brought the United States and Iran, which had maintained a relatively quiet detente since the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and who had restored diplomatic relations in 2007 with Iranian President Mehdi Karroubi, closer together. This came at the expense of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, whose government–run by archconservative Crown Prince and regent Nayef bin Abdul-Aziz Al Saud–lobbied heavily in Washington for a reversal, and quietly provided intelligence and money to the Hussein regime.

In the face of International chaos and economic ruin, the race broke in the direction of change. In the final poll of the election, Lieberman lagged behind in third place, with Ventura polling just ahead of the beleaguered Vice President. Ventura had called for an end to all of the country’s wars, a balanced budget amendment to the Constitution, as well as one abolishing the Senate to support a unicameral and expanded House of Representatives as the sole legislature, property tax reform, gay rights, medical marijuana, and abortion rights. Yet, try as he might, Ventura could never escape his flirtation with 9/11 trutherism with a majority of voters, and his running mate’s comments defending China’s reaction to the Tiananmen Square uprising didn’t help. With his anti-war position under fire by a media relentlessly focused on his 9/11 comments, Ventura’s instead tried to shift the focus to domestic policy, but there, his relatively thin record in Minnesota made his economic pitch fall flat, while stray comments at a campaign rally that appeared to blame Black and Latino homeowners with subprime mortgages for the state of the economy hurt him with key Democratic-leaning demographics.

Election Night 2008 was called almost as quickly as in 2004. While Romney won more than 400 electoral votes, the recount in Minnesota lasted weeks: when the dust cleared Ventura had defeated Romney by just under 100 voters. Winning both his home state and Maine's Second Congressional District, Ventura did what even Perot could not — actually win electoral votes. Despite Duverger’s law working against third parties in first-past-the-post elections, Reform gained its first Senate seats, with Angus King of Maine and Sarah Palin of Alaska’s Reform-aligned Independence Party. Four members were elected to the House of Representatives: while Rocky de la Fuente lost his seat, folk singer David Mallet won in Maine's Second, 26-year old former Somali refugee Ilhan Omar won a seat in Minneapolis in a four-way race following longtime Congressman Martin Olav Sabo’s retirement, Golisano deputy and former social worker Ann Costello won the open 25th District in New York, and unpopular freshman Idaho Congressman Bill Sali was defeated by Reformer and Sudan War veteran Matt Salisbury. This unlikely collection of legislators became colloquially known as “the Squad,” after Salisbury referred to them as “my squad in enemy territory.”

The new president’s transition period was consumed by responding to the myriad crises facing the country. Eager to save their lives and claim victory—over Lieberman, at least —Bashar al-Assad resigned as president and left Syria for exile in London, while Saddam Hussein fled Baghdad for his hometown in Tikrit in the face of defecting army units and advancing Iranian-backed militias. But, these crises would not be Reform’s responsibility; rather, they were an issue for President Romney.