Oh in all honesty I forgot about that, but Warren Beatty is a great choice. Also a good question as to who will play Jackie KennedyYou do remember that it's Warren Beatty who's going to act as JFK, Sr. in the movie JFK by director Oliver Stone in 1987 ITTL. It's Jackie Kennedy who handpicked Beatty to play the US President. If Beatty's going to play as JFK Mr. @President_Lincoln, who's going play as Jackie Kennedy with him?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Blue Skies in Camelot (Continued): An Alternate 80s and Beyond

- Thread starter President_Lincoln

- Start date

Idk. Learning about JFK, Jr. and his relationship with Christina Haag, I always thought a Kennedy having a long lasting relationship with a political future with a childhood friend is more down his alley.I also want to matched JFK, Jr. and Diana Spencer ITTL

Not anymore genius! Like I've already said here before many times, it would be JFK's daughter Caroline now who would inherit her father's footsteps in politics. With her marriage from Timothy Michael Kaine in 1983 ITTL, they might start first to as professors in their alumni university or wherever it may be, then Caroline would start to run for office by the time we arrived in the 90's ITTL.Idk. Learning about JFK, Jr. and his relationship with Christina Haag, I always thought a Kennedy having a long lasting relationship with a political future with a childhood friend is more down his alley.

I gathered that. I was pointing out an opinion, genius.Not anymore genius! Like I've already said here before many times, it would be JFK's daughter Caroline now who would inherit her father's footsteps in politics. With her marriage from Timothy Michael Kaine in 1983 ITTL, they might start first to as professors in their alumni university or wherever it may be, then Caroline would start to run for office by the time we arrived in the 90's ITTL.

Touch some grass

Looking forward to reading some Royal family drama at the end of the Seasaw Seventies 👀Will definitely be covering the Royal Family soonIncluding Prince Charles' courtship with Amanda Knatchbull.

I think 16 years of Democratic control in the White House is a bit much but I agree a about bipartisan nomination by a RepublicanI was thinking more of RFK serving 1981-1989 and then another Democrat wins in '88 appointing Kennedy to Chief Justice in '92. Or maybe whichever Republican wins in '88 could make a bipartisan nomination of former President Kennedy.

AgreedI think a Republican winning in '88 and making a bipartisan nomination of RFK in 92 makes the most sense. Assuming RFK does win re-election after 12 years I don't see another Democrat especially if it's Bentsen at the top of the ticket in 88.

Whatever you say genius, I just got myself a bad day earlier today and I apologize for my response. Chill down on saying touch some grass, we don't have much parks built nearby due to our country's lack of enough environmental awareness.I gathered that. I was pointing out an opinion, genius.

Touch some grass!

Okay Let's keep things civil like the author saysI gathered that. I was pointing out an opinion, genius.

Whatever you say genius, I just got myself a bad day earlier today and I apologize for my response. Chill down on saying touch some grass, we don't have much parks built nearby due to our country's lack of enough environmental awareness.

Touch some grass

My apologies to fellow geniuses here for what I've said earlier, it won't happen again.Okay, let's keep things civil like the author says.

Last edited:

My apologies. Just rubbed the wrong wayOkay Let's keep things civil like the author says

Understood. And my apologies as well. Just the messaging and repetition didn't really rub me the right wayI just got myself a bad day earlier today and I apologize for my response

In light of this, I am curious as to how Bobby is more tolerable towards gay rights. From what I gathered from a certain self-attributed Kennedy historian, Bobby was the most socially conservative of the three and was lock-step with the GOP on the social right (even considered homophobic in a reported historical work of a Kennedy aide). Would Rustin somehow be an influence for Bobby, or is this scenting discussed offhand (as much as it could be just politics, I feel that Bobby has a bit less wiggle room compared to, say, Doe).Bayard Rustin, the latter of whom had recently come out as gay, and began to agitate for LGBT+ awareness and rights, among many others

Bobby may be a Catholic and conservative in some instance but I think he would agree that nobody should be discriminated against based on who they sleep with. It even says in the chapter Where RFK announces his run that he was endorsed by the rainbow coalition which included Harvey Milk. What his personal beliefs may be I'm not sure. But politically I really believe he would be for Gay Rights.In light of this, I am curious as to how Bobby is more tolerable towards gay rights. From what I gathered from a certain self-attributed Kennedy historian, Bobby was the most socially conservative of the three and was lock-step with the GOP on the social right (even considered homophobic in a reported historical work of a Kennedy aide). Would Rustin somehow be an influence for Bobby, or is this scenting discussed offhand (as much as it could be just politics, I feel that Bobby has a bit less wiggle room compared to, say, Doe).

Last edited:

It's a mockup. Not an actual mod. Sorry.Where is this? I tried to find it on New Campaign Trail and couldn't

In light of this, I am curious as to how Bobby is more tolerable towards gay rights. From what I gathered from a certain self-attributed Kennedy historian, Bobby was the most socially conservative of the three and was lock-step with the GOP on the social right (even considered homophobic in a reported historical work of a Kennedy aide). Would Rustin somehow be an influence for Bobby, or is this scenting discussed offhand (as much as it could be just politics, I feel that Bobby has a bit less wiggle room compared to, say, Doe).

As PRM suggests here, I interpret RFK's views toward the LGBT+ community and gay rights as evolving over the course of his life. Though he may have been somewhat homophobic personally IOTL, he was also a fervent anti-communist (and did not even consider himself a "liberal") until the late 1960s. His views often changed with the times. He showed an open mind on many issues (especially social ones) and showed that he could grow with the nation. I believe that had RFK lived past 1968, he would have eventually become an ally of the LGBT+ community politically, as his brother Ted did. He would stand up for their rights and encourage tolerance and acceptance for all Americans. ITTL, Rustin is an influence on Bobby, much as John Lewis, Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta and other civil rights activists were.Bobby may be a Catholic and conservative in some instance but I think he would agree that nobody should be discriminated against based on who they sleep with. It even says in the chapter Where RFK announces his run that he was endorsed by the rainbow coalition which included Harvey Milk. What his personal beliefs may be I'm not sure. But politically I really believe he would be for Gay Rights.

Great stuff Mr. President! It’s good to hear about that happening ITTL.As PRM suggests here, I interpret RFK's views toward the LGBT+ community and gay rights as evolving over the course of his life. Though he may have been somewhat homophobic personally IOTL, he was also a fervent anti-communist (and did not even consider himself a "liberal") until the late 1960s. His views often changed with the times. He showed an open mind on many issues (especially social ones) and showed that he could grow with the nation. I believe that had RFK lived past 1968, he would have eventually become an ally of the LGBT+ community politically, as his brother Ted did. He would stand up for their rights and encourage tolerance and acceptance for all Americans. ITTL, Rustin is an influence on Bobby, much as John Lewis, Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta and other civil rights activists were.

Makes you look forward to seeing RFK handlng AIDS better than Reagan could ever think ofGreat stuff Mr. President! It’s good to hear about that happening ITTL.

Exactly Mr. President, RFK is our last hope to beat that Reagan in the 1980 US Presidential Election ITTL. It's over Reagan, we have the high ground! Kennedy-Bentsen 1980: Leadership for the Decade!As @PRM suggests here, I interpret RFK's views toward the LGBT+ Community and Same-Sex Rights as evolving over the course of his life. Though he may have been somewhat homophobic personally IOTL, he was also a fervent Anti-Communist (and did not even consider himself a "Liberal") until the Late 1960's. His views often changed with the times. He showed an open mind on many issues (especially social ones) and showed that he could grow with the nation. I believe that had RFK lived Past-1968, he would have eventually become an ally of the LGBT+ Community politically, as his brother Ted did. He would stand up for their rights and encourage tolerance and acceptance for all Americans. ITTL, Rustin is an influence on Bobby, much as John Lewis, Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta and other Civil Rights Activists were.

Reagan: You underestimate our power.Exactly Mr. President, RFK is our last hope to beat that Reagan in the 1980 US Presidential Election ITTL. It's over Reagan, we have the high ground! Kennedy-Bentsen 1980: Leadership for the Decade!

RFK: Try us.

I just hope Reagan has a concession speech prepared

Reagan better be prepared for his concession speech because he ain't going to win this time geniuses!Reagan: You underestimate our power.

RFK: Try us.

I just hope Reagan has a concession speech prepared.

Last edited:

Chapter 139

CONTENT WARNING: This chapter contains references to military combat and some instances of crimes against humanity. If you are not in the headspace to read about such things just now, please return to this one a little later on.

Chapter 139 - Stomp! - The Origins and Opening Stages of the Iran-UAR War

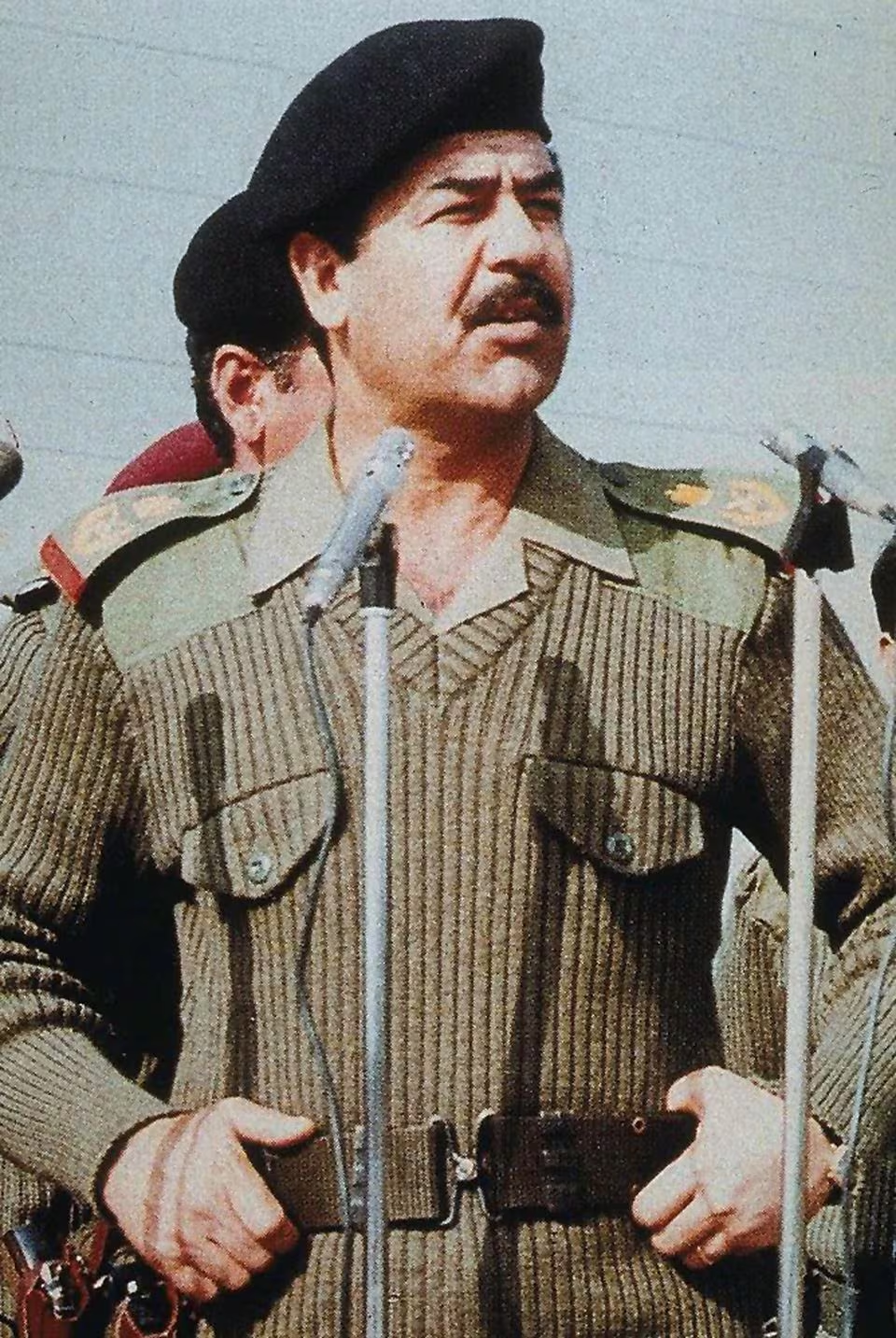

Above: President Saddam Hussein and Vice President Hafiz al-Assad of the United Arab Republic, which was officially proclaimed at the 1979 summit of the Arab League in Baghdad. The two leaders are shown here shaking hands with Algerian Foreign Minister Abdelaziz Bouteflika and Abd al-Halim Khaddam, UAR Foreign Minister.

Above: President Saddam Hussein and Vice President Hafiz al-Assad of the United Arab Republic, which was officially proclaimed at the 1979 summit of the Arab League in Baghdad. The two leaders are shown here shaking hands with Algerian Foreign Minister Abdelaziz Bouteflika and Abd al-Halim Khaddam, UAR Foreign Minister.

“We're gonna stomp

All night

In the neighborhood

Don't it feel alright?

Gonna stomp

All night

Wanna party 'til the mornin' light” - “Stomp!” by the Brothers Johnson

“Strike the enemy’s settlements, turn them into dust, pave the Arab roads with the skulls of Persians.” - Hafiz al-Assad

“Iraq is a great nation now, as it has been at times throughout history. Nations generally ‘go to the top’ only once. Iraq, however, has been there many times, before and after Islam. Iraq is the only nation like this in the world. This ‘gift’ was given to the Iraqi people by God. When Iraqi people fall, they rise again.” - Saddam Hussein

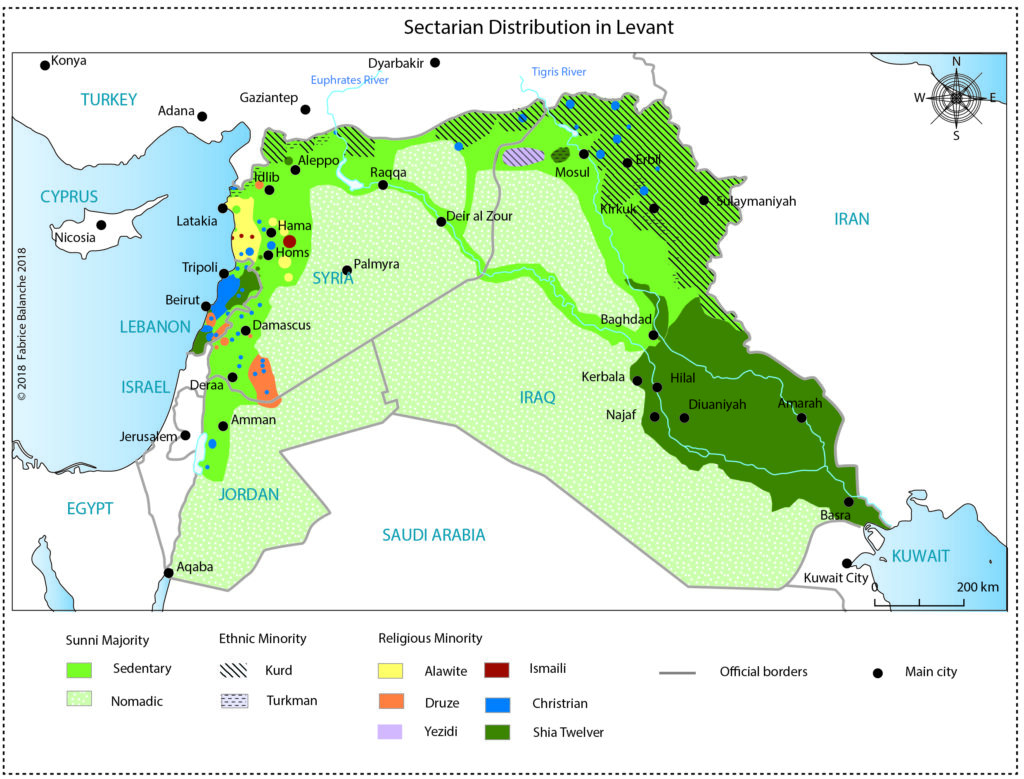

In 1978, then-Iraqi Vice President Saddam Hussein engaged in talks with fellow Baathist Hafiz al-Assad, President of Syria about the possibility of unifying the states of Iraq and Syria.

By that time, Saddam had become the effective leader of the Ba'ath party in his country due to Iraqi President Ahmed Hussein Al-Bakr's chronic health issues. A major demand of Saddam was the unification of both the Syrian and Iraqi wings of the Ba'ath party, as the first step to integrate Syria with Iraq. He also sought the rehabilitation of Michel Aflaq, who was on the kill-list of the Syrian Ba'ath party, and make Aflaq the head of a re-unified Ba'ath Party. It was reported that Assad initially rejected these demands, but was persuaded to accept them after meeting personally with Hussein, who assured him that both of them would play a prominent role in the newly unified country. The pact between them, sealed with a handshake, was not made public until July the following year.

By then, on July 19th, Hussein had forced the resignation of the ailing President al-Bakr. Hussein ascended to the presidency and hurriedly convened an “emergency session” of party leaders on July 22nd.

During the assembly, which he ordered to be videotaped, he claimed to have uncovered a “fifth column” within the party. Abdul-Hussein "confessed" to being part of an “Iranian-financed faction” established in 1975 that played a major role in the Iranian-backed plot against the Iraqi government. He also gave the names of 68 alleged co-conspirators. These were removed from the room one by one as their names were called and taken into custody. After the list was read, Saddam congratulated those still seated in the room for their past and future loyalty. Those arrested at the meeting were subsequently tried together and found guilty of treason. Twenty-two men, including five members of the Revolutionary Command Council were sentenced to execution. Those spared were given weapons and directed to execute their comrades.

A similar, if less bloodthirsty purge had already occurred in Damascus, with Assad ordering opponents of his own regime removed from the party and jailed.

That same day, July 22nd, 1979, Hussein and Assad used the Summit of the Arab League simultaneously occurring in Baghdad to announce the formation of the Second United Arab Republic - a successor state to both Iraq and Syria. The new state, the two men claimed, would stand “united for a Ba’athist future, one which fulfilled our shared principles: secularism; Arab nationalism; Pan-Arabism; and Arab socialism.” A constitutional convention was scheduled to be held in Damascus the following month. This was a calculated “gift” to Assad, to increase his prestige. After all, Saddam did not intend for anyone but himself to be president of the newly united republic.

The Convention confirmed what most outside observers would have surmised the forthcoming state to be. A unitary presidential republic with an anemic legislature and judicial system, the new republic’s government empowered its president in the extreme. The vice president would also serve as prime minister, and preside over this legislature, the so-called “Federation Council”. To the surprise of approximately no one, Saddam Hussein was sworn in as the Second UAR’s first president while Assad became vice president and prime minister. Baghdad, the new nation’s largest city, became the capital, with Damascus being given special status as a “city-district” with special tax exemptions and other privileges.

At the time of unification (July 1979), Syria had a population of approximately 8.9 million, compared to Iraq’s 13.65 million, which, upon first glance might make Syria seem like something of a “junior partner” in the new republic. On the contrary, part of why Saddam was so intent on integrating Syria into “his'' burgeoning country was the need to secure, for himself, a reliable ethnic, political, and religious power base.

In pre-unification Iraq, Saddam was a Sunni Muslim ruling a largely Shia population, especially in the heavily populated southern regions, close to the Persian Gulf. By “unifying” with Syria, he added nearly 9 million more mostly Arab, mostly Sunni citizens to his nation. The new UAR’s total population neared 22 million. Indeed, though both countries contained sizable minorities of various ethnicities and other religions, most notably the Kurds in their northern marches near the Turkish border, the move to unify strengthened the positions of both Hussein and Assad.

While the commanders of both former countries’ militaries worked to integrate their armed forces into a single, unified fighting force, Assad turned his attention to domestic policy - broadly favoring integrationism and a focus on Pan-Arab education. Hussein, meanwhile, took over foreign affairs.

Saddam’s geopolitical goals were as likely to be informed by his own personal ambitions as they were by his Baathist ideology. Fancying himself a modern day ruler of a successor state to the ancient empires of Mesopotamia and Babylon, Saddam privately spoke of himself as “the son of Nebuchadnezzar '', and encouraged his groveling underlings to do the same. He truly believed that his country “deserved” to lead the Arab world, and to achieve hegemony over the Persian Gulf, particularly in the aftermath of Egypt’s “betrayal” by signing the Walker’s Point Accords with Israel. Far from harboring genuine sympathy for the Palestinian people and their cause, however, the UAR’s president mostly paid mere lip service to Pan-Arabism, and saw the Palestinians as pawns to be used and discarded when convenient.

Hussein’s first goal was to establish his new United Arab Republic as a regional power to be reckoned with, on par with any of its neighbors. Toward this end, he spent the latter half of 1979 funneling Iraq and Syria’s considerable oil wealth into beefing up the UAR’s armed forces. In addition to recruitment drives and conscription, Hussein continued purchases of small arms, artillery, 1,600 tanks and armored vehicles, and even 200 aircraft, including 50 MiG-23 jet fighters from the Soviet Union. The last of these arrived in early 1980 and bolstered the UAR’s air force. Hussein was never a close ally of the Soviets, but given American President Udall’s refusal to sell arms to regimes such as Hussein’s, the UAR’s president really had little choice in the matter. He allowed Moscow to continue to see him as a nominal ally in the Middle East, so long as it meant continued financial and military support, not to mention diplomatic protection on the UN Security Council.

Above: Soviet-made MiG-23 jet fighters and T-72 tanks, staples of the United Arab Republic’s air force and armored divisions, respectively.

With his grip on power reasonably secure and his military now outfitted with modern (and expensive) equipment, Saddam felt a strong desire to, as one American military observer later put it bluntly, “play with his new toys”. He surveyed the geopolitical situation in the Middle East at the time, searching for a target. Ideally, this country would be one which did not have a strong tilt one way or another in the Cold War and one on which Saddam could produce (or fabricate) a reasonable casus belli. By the spring of 1980, he found one.

Just under a year after the proclamation of the Democratic Republic of Iran and the unveiling of its new constitution, the people of the new republic went to the polls to elect their president (head of state) and assemble their new legislature.

As expected, Ayatollah Montazeri, champion of both traditional Islamic values and democratic principles, was easily elected to a full term in the presidency. In the National Assembly, various parties campaigned hard to win a majority. Though at first, polls predicted a victory for the “Progressive Revolutionary Bloc”, a coalition of communist, socialist, and other far-left parties (making more than a few government and military officials in Tehran nervous), in the end, a “Grand Coalition” of liberals, conservatives, and the National Front won a slim majority. Also forming a major, third bloc were unreconstructed monarchists and Islamic fundamentalists, both of whom were thoroughly unhappy with the new republic as it stood. 73 years old, Prime Minister Bazargan stepped down as leader of the Coalition, in favor of his deputy, 49 year old Ebrahim Yazdi.

Likewise a defender of liberal democracy and Iranian nationalism, Yazdi was born in Qazvin on September 26th, 1931. He studied pharmacy at the University of Tehran; then, upon graduation, he received a Master’s of Philosophy. After the military coup of 1953, which deposed the government of Mohammad Mossadegh, Yazdi joined the underground National Resistance Movement of Iran. This organization strongly opposed the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Yazdi traveled to the United States in 1961 to continue his education and in the US, continued his involvement in political activities against the monarchy. In 1975, Yazdi was tried in absentia in an Iranian military court and condemned to ten years imprisonment, with orders issued for his arrest upon return to Iran. Because of his activities, he was unable to return to Iran and remained in the United States until July of 1977. He became a naturalized US citizen in Houston in 1971, but later agreed to return to his homeland to participate in the new, republican government. After being granted a pardon by the provisional government, Yazdi then joined the Foreign Ministry, and became a member of Prime Minister Bazargan’s Freedom Party.

Many world leaders, who swiftly called Yazdi to congratulate him on his electoral victory, wondered what sort of man this new Prime Minister would be. Iran was, after all, a middle and regional power. Bazargan and the provisional government had sworn neutrality in the Cold War, and had begun pushing Iran toward the Non-Aligned Movement. But there were many within Tehran, Moscow, and Washington who hoped for the republic to take a different path.

For one thing, geopolitics made prolonged Iranian neutrality difficult. To Iran’s east lay Soviet-aligned Afghanistan and Pakistan. To its west, stood the United Arab Republic, another Soviet ally. Control of the Persian Gulf and with it, the vast oil resources of the Middle East was far too tempting an opportunity for the world’s superpowers to pass up. Both US Secretary of State George Ball and Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko understood that the energy crises of the 1970s were largely the result of instability in the Middle East. Though the Udall Administration had taken great pains to begin to cure America of its addiction to foreign oil, it would take several years, if not decades, for their efforts to pay off. In the meantime, the world’s hunger for energy meant that the Middle East, and its resources, remained crucial.

Given that Yazdi was a naturalized US citizen, and had spent many years in the United States pursuing his education and remaining safe from the Shah’s regime, many in Washington and Moscow assumed that he would, naturally, favor rapprochement with the US. These experts were largely correct in this assessment.

Yazdi pointed to the Udall Administration’s condemnation of the Shah and refusal to back him, as well as the historical precedent of the Kennedy Doctrine as proof that America would now support Iran pursuing their own national interest, as defined by their democratically-elected government. Others in Tehran, however, even including members of his own ministry, were less certain. Memories of 1953 were still firmly held. America had been quick then to discard her dedication to democracy in the name of imperial interests, alongside the British. Thus, for as friendly to the US as Yazdi was, he knew that he could not pursue a Western alignment too strongly, or too quickly. He was head of an unsteady coalition, the only thing (in his mind) standing between Iran and an Islamic theocracy (led by Mostafa Khomeini) or a Soviet-backed Communist coup.

As if this situation were not shaky enough for the new government, a crisis emerged in September of 1980 that would test the very foundations of the Democratic Republic - war with the UAR.

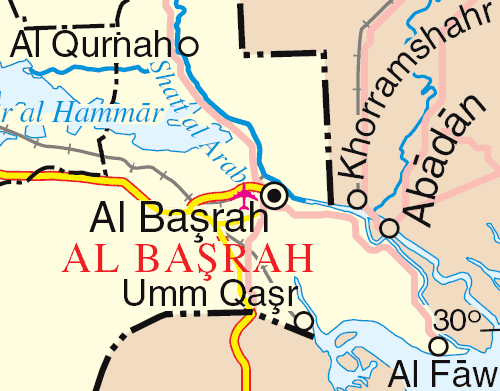

In April 1969, Iran abrogated the 1937 treaty over the Shatt al-Arab (a 120 mile long river at the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates that flows into the Persian Gulf), and Iranian ships stopped paying tolls to Iraq when they used the river. The Shah argued that the 1937 treaty was unfair to Iran because almost all river borders around the world ran along the thalweg, and because most of the ships that used the Shatt al-Arab were Iranian. Iraq threatened war over the move at the time, but on April 24th, 1969, an Iranian tanker (escorted by Iranian warships) sailed down the Shatt al-Arab into the Gulf. Iraq - being the militarily weaker state - did nothing. Though from Iran’s perspective, the issue appeared to be settled, from Iraq’s (and subsequently, the UAR’s), it was anything but.

The Iranian Revolution of 1978-79 reopened the issue, and inflamed tensions between the two nations once again.

Initially, Hussein and Assad were pleased by news that the Shah, their old enemy, had been overthrown. This feeling swiftly dissipated, however. The new republican government in Tehran refused to revisit the issue of the Shatt al-Arab, which it likewise considered to be settled law. Further, there were cultural and religious tensions as well.

Though officially a secular nation, Iran, with its largely Shia population, represented the branch of Islam opposite Saddam Hussein. For Shia Iraqis, the Revolution - which overthrew an unpopular tyrant “forcing” secularization upon an unwilling, conservative populace - seemed like it could serve as an inspiration. Hussein was terrified of this possibility. Thus, in Saddam’s mind, crushing Iran, humiliating them utterly, was an utmost priority.

His diplomatic play over the Shatt al-Arab (and to annex the Khuzestan province) began in February with an ultimatum issued by his ambassador in Tehran. In the brash, provocative text of the document, Saddam demanded that Iran cede the region to the UAR “as a show of good faith toward continued friendship between our nations”. Yazdi’s government, assuming the play to be some kind of saber-rattling bluff, refused to respond. The Prime Minister did, however, authorize back channel talks to try and arrange for a summit between himself and Hussein to “renegotiate a mutually beneficial relationship along the Gulf”. Hussein likewise rebuffed these talks.

On March 8th 1980, the time-limit on the ultimatum ran out. The UAR announced that it was withdrawing its ambassador from Iran, downgraded its diplomatic ties to the charge d'affaires level, and demanded that Iran do the same. In response, the following day, Iran declared the UAR’s ambassador persona non grata, and withdrew their own ambassador.

Slowly, the drums of war began to beat.

On the eve of the revolution in 1978, international experts in military science had assessed that Iran's armed forces were the fifth most powerful in the world. (Behind the United States, Soviet Union, United Kingdom, and France). With a well-trained officer corps and large stockpiles of high quality American and British-made equipment, the Iranians seemed like a truly fearsome opponent for any nation that dared to take them on. In the aftermath of the Shah’s abdication, however, the military was rocked by a series of successive blows that severely weakened their position.

First, as the Bazargan-led Provisional Government attempted to join the Non-Aligned Movement, the political cost of continuing to purchase Western military equipment rose. In an attempt to secure the new government’s supposedly neutral footing, all shipments of military aid from the West were ordered to cease. This resulted in a shortage of spare parts, especially for vehicles like tanks, armored personnel carriers, and crucially, the American-made F-14 Tomcat fighter jets. Though the Yazdi government quickly attempted to remedy this and would do so after the outbreak of war in September, in the months leading up to the Iraqi invasion, Iranian equipment and logistics were unnecessarily weakened by a lack of supply. See the comparison below:

Imbalance of Power (Sept. 1980):

Number of Soldiers

United Arab Republic - ~350,000 - 24 divisions and nine brigades

Iran - ~415,000 - 28 divisions and five brigades

Tanks

United Arab Republic - ~3,000

Iran - ~2,000 (Approximately 1,000 of which were operable)

Fighter Aircraft

United Arab Republic - 362

Iran - 455 (350 operable)

Helicopters

United Arab Republic - 150

Iran - 500 (200 operable)

Artillery

United Arab Republic - 1,000

Iran - 1,000 (300 operable)

Above: Iranian Mobarez (“Warrior”) tanks, modeled on the British Chieftan (left); American F-14 Jet Fighters, the jet of choice for the Iranian air force in 1980 (right).

Second, along with the rest of Iranian society, the military was still rife with internal divisions and shifting loyalties amidst the relative chaos of transitioning from a constitutional monarchy to a democratic republic. Though most major generals and other senior staff officers remained after the Shah’s abdication and the unveiling of the new constitution, many rank and file soldiers were unsure about the future of their country. Some held views sympathetic to the radical Islamists whom they felt were “ostracized” by Yazdi’s government, as he had not invited them to join the Grand Coalition. Even those soldiers that did support the new republic (including most of the officers) felt that the country was not ready for any kind of armed conflict. One general summed up the military’s assessment of Iran’s defense when he wrote to Prime Minister Yazdi in May 1980:

“At this time, we are best suited by taking a firmly defensive posture with our neighbors. We claim that our position is not to stand alone in the world, but will any of our fellow ‘unaligned’ powers come to our aid in a time of crisis? I think not.”

Meanwhile, UAR military intelligence reported in July 1980 that despite Iran's optimistic rhetoric, “it is clear that, at present, Iran has no power to launch wide offensive operations against us, or to defend on a large scale.” Saddam, upon reading the report in his office at the Presidential palace in Baghdad was said to have smiled wide. Days before the UAR’s invasion and in the midst of rapidly escalating cross-border skirmishes, UAR military intelligence again reiterated on September 14th that “the enemy deployment organization does not indicate hostile intentions and appears to be taking on a more defensive mode.”

In addition, the area around the Shatt al-Arab posed no obstacle for the Iraqis and Syrians, as they possessed river crossing equipment. The UAR correctly deduced that Iran's defenses at the crossing points around the Karkheh and Karoun Rivers were undermanned and that the rivers could be easily crossed. Arab intelligence was also informed that the Iranian forces in Khuzestan Province (which consisted of two divisions prior to the revolution) now only consisted of several ill-equipped and under-strength battalions. Only a handful of company-sized tank units remained operational.

On September 10th, 1980, the UAR acted on these reports, and forcibly reclaimed territories in Zain al-Qaws and Saif Saad that Iraq had been promised under the terms of the 1975 Algiers Agreement, but that Iran had never handed over, leading to both Iran and the UAR declaring the treaty null and void, on September 14th and 17th, respectively. As a result, the only outstanding border dispute between Iran and UAR at the time of the UAR invasion of September 22nd was the question of whether Iranian ships would fly UAR flags and pay navigation fees for a stretch of the Shatt al-Arab river spanning several miles.

Saddam launched a full-scale invasion of Iran on September 22nd, 1980, beginning in the air.

The UAR’s Air Force launched surprise airstrikes on ten Iranian airfields with the objective of destroying the Iranian Air Force. The attack failed to damage the Iranian Air Force significantly. It damaged some of Iran's air base infrastructure, but failed to destroy a significant number of aircraft. Saddam’s Air Force was only able to strike in depth with a few of his jet fighters. Iran had also built hardened aircraft shelters where most of its combat aircraft were stored.

The next day, a ground invasion followed along a front measuring 644 km (400 miles) in three simultaneous attacks. Saddam hoped an attack on Iran would cause such a blow to Iran's prestige that it would lead to the new Yazdi government's downfall.

Of the UAR's eight divisions that invaded by ground, six were sent to Khuzestan, which was located near the border's southern end, to cut off the Shatt al-Arab from the rest of Iran, as well as to establish a “territorial security zone”. The remaining two invaded across the northern and central sections of the border to prevent a counter-attack.

Two of the six UAR divisions, one mechanized and one armored, operated near the southern end of the border, and began a siege of the strategically important port cities of Abadan and Khorramshahr. On the central front, Saddam’s troops occupied Mehran, advanced towards the foothills of the Zagros Mountains, and were able to block the traditional Tehran–Baghdad invasion route by securing territory forward of Qasr-e Shirin, Iran. To the North, the UAR attempted to establish a strong defensive position opposite Sulaymaniyah to protect the oil complex at Kirkuk. Saddam had hoped that ethnic Arabs in Khuzestan would rise up in rebellion and join their “liberators” against Iran, but this failed to materialize. The vast majority of ethnic Arabs in the area remained loyal to Tehran.

Western military observers would later characterize the entire invasion as “badly led” and “consisting of troops with staggeringly low morale for such an enterprise”. The latter of these observations could, perhaps, be attributed to the fact that many of the UAR’s rank and file soldiers were Syrian conscripts, who felt little to no attachment to their new president and his dreams of hegemony. Saddam did not fully trust Assad, and so refused to let his own “Republican Guard” units, fully loyal to Saddam, be sent to the front. The Guard remained in the rear, never far from Baghdad.

Perhaps attempting to make up for his troops’ low morale, Saddam authorized the use of chemical weapons against the Iranians, a clear violation of the Geneva Convention and other statutes of international law. The first known instance probably took place during the fighting around Shush.

Though the UAR’s air invasion took the Iranians by surprise, the Iranian air force retaliated the following day with a large-scale counterattack against Arab air bases and infrastructure. Groups of F-4 Phantom and F-5 Tiger fighter jets attacked targets throughout Iraq, including oil refineries, dams, and petrochemical plants. Another set of targets were Mosul Air Base, Baghdad, and the Kirkuk oil refinery. The UAR was shocked at the strength of the retaliation, which caused heavy losses and severe economic disruption, but the Iranians took heavy losses as well as losing many aircraft and aircrews to Arab air defenses.

Meanwhile, UAR air attacks on Iran were repelled by Iran's F-14A Tomcat interceptor fighter jets, using AIM-54A Phoenix missiles, which downed a dozen of the UAR's Soviet-built fighters in the first two days of battle alone. Though Iranian ground forces scrambled to deliver a coordinated counterattack, the Navy attacked Basra, Iraq, destroying oil tankers near the port of Al-Faw, reducing the UAR’s ability to export oil, a critical economic lifeline. In general, Tehran ordered a general retreat of ground forces to the cities, where they could dig in and organize a defense. This left the countryside to the invaders, who often looted, pillaged, and committed other atrocities against the civilian population.

The mountainous border between Iran and Iraq made a deep ground invasion almost impossible by either side. Thus, air strikes and long-range artillery were used instead. The invasion's first waves were a series of airstrikes targeted at Iranian airfields. The UAR also attempted to bomb Tehran into submission.

On September 22nd, a prolonged battle broke out in the city of Khorramshahr, eventually leaving around 7,000 dead on each side. This led to Khorramshahr gaining the nickname, “the City of Blood” amongst Iranian soldiers. The battle began with Saddam’s armored and mechanized units approaching the city in a sickle formation, only to be beaten back by fierce resistance. Iranians, many armed with improvised weapons and Molotov cocktails, fought back the invaders house by house, and street by street. Arab air superiority became the deciding factor, however, and by September 30th, the outskirts of the city had been overrun. Over the next month, the fighting continued until at last, on the 24th, the beleaguered Iranians withdrew, surrendering the city.

Despite the setback, however, the Iranians used the delay granted them against the invaders to fully mobilize and deploy their armed forces. When Saddam ordered his troops to advance toward Dezful and Ahvaz, his units were badly damaged by revitalized Iranian air power and artillery strikes. The Iranian air force struck the invaders’ supply depots, robbing them of vital fuel and water. Simultaneously, in November, Iran launched Operation Pearl, a combined sea and air attack that wound up destroying approximately 75% of the UAR’s naval presence in the Persian Gulf, along with most of its southern radar sites. When the Arabs laid siege to Abadan, they were unable to blockade the port, allowing the city to be resupplied via the sea.

Quickly, Saddam’s strategic reserves of gas and equipment were depleted. His republic lacked the resources necessary to carry on any further offensives for the rest of the year. On December 7th, 1980, Saddam ordered a general halt on the front, and for his forces to defend “all captured territory” and prepare Khuzestan for “complete annexation by the conclusion of the following year [1981].”

Diplomatically, the Iran-UAR War became a hot button issue, another flashpoint in the Cold War.

In New York, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution calling on both Baghdad and Tehran to “settle any and all disputes peacefully, submitting them, if necessary, for arbitration in the Hague”. Andrew Young, American Ambassador to the UN, decried this resolution as “weak and needlessly vague in its condemnation”. So far as the US was concerned, blame for the war lay squarely at the feet of Saddam Hussein and his insatiable ambition. The USSR, however, disagreed.

Shortly after the war began, Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko made a top secret trip to Damascus to meet with Hussein and Assad to lend his and his country’s support. The New Troika had hoped to bring Iran under the Soviet sphere of influence, but the defeat of the far-left coalition at the ballot box early in 1980 seemed to make such a shift unlikely. Instead, Gromyko and his fellows in Moscow calculated that by supporting Saddam’s invasion, they may be able to drive the American-friendly Yazdi from power. It was a sort of three-dimensional chess, thinking that they could make Tehran amenable to Soviet interests by force. But it was what they had.

The Soviets voted against condemning Saddam alone for the invasion in the UN, claiming that Tehran had “refused to submit legitimate territorial and economic concerns to international courts for arbitration”. Further, they increased their shipments of military equipment and spare parts to the UAR, allowing Saddam’s forces (in the early stages, at least) to repair and replace their damaged equipment far quicker than the non-aligned Iranians.

Generally speaking, the American public were largely against any kind of military response to Iraq’s invasion. Most saw the war as far-off and far removed from them and their daily lives. Many in Washington, however, grew nervous. Conflict in the Persian Gulf sent already high oil (and therefore gasoline) prices even higher. To prevent a spike in inflation, which had only just gotten under control, Udall authorized a small release from the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve, and encouraged the Federal Reserve to keep interest rates high. This was merely a band-aid on the problem, however. In the long run, a diplomatic solution was necessary.

The war thus, unsurprisingly, became a campaign issue in the 1980 election.

Both Ronald Reagan and Bob Kennedy favored increasing shipments of aid to the Democratic Republic of Iran, though they disagreed on the particulars. Reagan called for Iran to “publicly denounce the Soviet Union and stand beside the free peoples of the world” before it could expect substantial American aid. Kennedy, meanwhile, shied away from such imperialist language, and instead called for “immediate aid and unequivocal support not just for Iranians, but for freedom-seeking people everywhere in the world”. For their part, the Iranian people seemed to prefer Kennedy over Reagan, as the former had a reputation as a hotheaded hawk, while the latter was seen as cool, calm, and collected in a crisis. RFK had also been a nemesis of the Shah during Kennedy’s brother’s administration, further increasing his credibility among the post-revolution Iranian populace.

Negotiations did begin between Ebrahim Yazdi and Mo Udall’s respective administrations to start the crucial shipments of spare parts flowing. But major shipments would not be ready until the following year. Until then, both Iran and the UAR settled in for what they feared would be a long, bloody conflict.

Chapter 139 - Stomp! - The Origins and Opening Stages of the Iran-UAR War

“We're gonna stomp

All night

In the neighborhood

Don't it feel alright?

Gonna stomp

All night

Wanna party 'til the mornin' light” - “Stomp!” by the Brothers Johnson

“Strike the enemy’s settlements, turn them into dust, pave the Arab roads with the skulls of Persians.” - Hafiz al-Assad

“Iraq is a great nation now, as it has been at times throughout history. Nations generally ‘go to the top’ only once. Iraq, however, has been there many times, before and after Islam. Iraq is the only nation like this in the world. This ‘gift’ was given to the Iraqi people by God. When Iraqi people fall, they rise again.” - Saddam Hussein

In 1978, then-Iraqi Vice President Saddam Hussein engaged in talks with fellow Baathist Hafiz al-Assad, President of Syria about the possibility of unifying the states of Iraq and Syria.

By that time, Saddam had become the effective leader of the Ba'ath party in his country due to Iraqi President Ahmed Hussein Al-Bakr's chronic health issues. A major demand of Saddam was the unification of both the Syrian and Iraqi wings of the Ba'ath party, as the first step to integrate Syria with Iraq. He also sought the rehabilitation of Michel Aflaq, who was on the kill-list of the Syrian Ba'ath party, and make Aflaq the head of a re-unified Ba'ath Party. It was reported that Assad initially rejected these demands, but was persuaded to accept them after meeting personally with Hussein, who assured him that both of them would play a prominent role in the newly unified country. The pact between them, sealed with a handshake, was not made public until July the following year.

By then, on July 19th, Hussein had forced the resignation of the ailing President al-Bakr. Hussein ascended to the presidency and hurriedly convened an “emergency session” of party leaders on July 22nd.

During the assembly, which he ordered to be videotaped, he claimed to have uncovered a “fifth column” within the party. Abdul-Hussein "confessed" to being part of an “Iranian-financed faction” established in 1975 that played a major role in the Iranian-backed plot against the Iraqi government. He also gave the names of 68 alleged co-conspirators. These were removed from the room one by one as their names were called and taken into custody. After the list was read, Saddam congratulated those still seated in the room for their past and future loyalty. Those arrested at the meeting were subsequently tried together and found guilty of treason. Twenty-two men, including five members of the Revolutionary Command Council were sentenced to execution. Those spared were given weapons and directed to execute their comrades.

A similar, if less bloodthirsty purge had already occurred in Damascus, with Assad ordering opponents of his own regime removed from the party and jailed.

That same day, July 22nd, 1979, Hussein and Assad used the Summit of the Arab League simultaneously occurring in Baghdad to announce the formation of the Second United Arab Republic - a successor state to both Iraq and Syria. The new state, the two men claimed, would stand “united for a Ba’athist future, one which fulfilled our shared principles: secularism; Arab nationalism; Pan-Arabism; and Arab socialism.” A constitutional convention was scheduled to be held in Damascus the following month. This was a calculated “gift” to Assad, to increase his prestige. After all, Saddam did not intend for anyone but himself to be president of the newly united republic.

The Convention confirmed what most outside observers would have surmised the forthcoming state to be. A unitary presidential republic with an anemic legislature and judicial system, the new republic’s government empowered its president in the extreme. The vice president would also serve as prime minister, and preside over this legislature, the so-called “Federation Council”. To the surprise of approximately no one, Saddam Hussein was sworn in as the Second UAR’s first president while Assad became vice president and prime minister. Baghdad, the new nation’s largest city, became the capital, with Damascus being given special status as a “city-district” with special tax exemptions and other privileges.

At the time of unification (July 1979), Syria had a population of approximately 8.9 million, compared to Iraq’s 13.65 million, which, upon first glance might make Syria seem like something of a “junior partner” in the new republic. On the contrary, part of why Saddam was so intent on integrating Syria into “his'' burgeoning country was the need to secure, for himself, a reliable ethnic, political, and religious power base.

In pre-unification Iraq, Saddam was a Sunni Muslim ruling a largely Shia population, especially in the heavily populated southern regions, close to the Persian Gulf. By “unifying” with Syria, he added nearly 9 million more mostly Arab, mostly Sunni citizens to his nation. The new UAR’s total population neared 22 million. Indeed, though both countries contained sizable minorities of various ethnicities and other religions, most notably the Kurds in their northern marches near the Turkish border, the move to unify strengthened the positions of both Hussein and Assad.

While the commanders of both former countries’ militaries worked to integrate their armed forces into a single, unified fighting force, Assad turned his attention to domestic policy - broadly favoring integrationism and a focus on Pan-Arab education. Hussein, meanwhile, took over foreign affairs.

Saddam’s geopolitical goals were as likely to be informed by his own personal ambitions as they were by his Baathist ideology. Fancying himself a modern day ruler of a successor state to the ancient empires of Mesopotamia and Babylon, Saddam privately spoke of himself as “the son of Nebuchadnezzar '', and encouraged his groveling underlings to do the same. He truly believed that his country “deserved” to lead the Arab world, and to achieve hegemony over the Persian Gulf, particularly in the aftermath of Egypt’s “betrayal” by signing the Walker’s Point Accords with Israel. Far from harboring genuine sympathy for the Palestinian people and their cause, however, the UAR’s president mostly paid mere lip service to Pan-Arabism, and saw the Palestinians as pawns to be used and discarded when convenient.

Hussein’s first goal was to establish his new United Arab Republic as a regional power to be reckoned with, on par with any of its neighbors. Toward this end, he spent the latter half of 1979 funneling Iraq and Syria’s considerable oil wealth into beefing up the UAR’s armed forces. In addition to recruitment drives and conscription, Hussein continued purchases of small arms, artillery, 1,600 tanks and armored vehicles, and even 200 aircraft, including 50 MiG-23 jet fighters from the Soviet Union. The last of these arrived in early 1980 and bolstered the UAR’s air force. Hussein was never a close ally of the Soviets, but given American President Udall’s refusal to sell arms to regimes such as Hussein’s, the UAR’s president really had little choice in the matter. He allowed Moscow to continue to see him as a nominal ally in the Middle East, so long as it meant continued financial and military support, not to mention diplomatic protection on the UN Security Council.

Above: Soviet-made MiG-23 jet fighters and T-72 tanks, staples of the United Arab Republic’s air force and armored divisions, respectively.

With his grip on power reasonably secure and his military now outfitted with modern (and expensive) equipment, Saddam felt a strong desire to, as one American military observer later put it bluntly, “play with his new toys”. He surveyed the geopolitical situation in the Middle East at the time, searching for a target. Ideally, this country would be one which did not have a strong tilt one way or another in the Cold War and one on which Saddam could produce (or fabricate) a reasonable casus belli. By the spring of 1980, he found one.

…

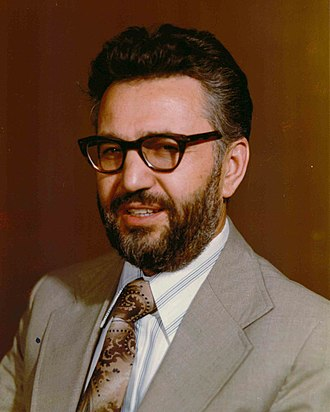

Above: The flag of the Democratic Republic of Iran (left); Ebrahim Yazdi, leader of the center-left Freedom Party, elected Prime Minister of Iran following the May 1980 legislative elections (right).Just under a year after the proclamation of the Democratic Republic of Iran and the unveiling of its new constitution, the people of the new republic went to the polls to elect their president (head of state) and assemble their new legislature.

As expected, Ayatollah Montazeri, champion of both traditional Islamic values and democratic principles, was easily elected to a full term in the presidency. In the National Assembly, various parties campaigned hard to win a majority. Though at first, polls predicted a victory for the “Progressive Revolutionary Bloc”, a coalition of communist, socialist, and other far-left parties (making more than a few government and military officials in Tehran nervous), in the end, a “Grand Coalition” of liberals, conservatives, and the National Front won a slim majority. Also forming a major, third bloc were unreconstructed monarchists and Islamic fundamentalists, both of whom were thoroughly unhappy with the new republic as it stood. 73 years old, Prime Minister Bazargan stepped down as leader of the Coalition, in favor of his deputy, 49 year old Ebrahim Yazdi.

Likewise a defender of liberal democracy and Iranian nationalism, Yazdi was born in Qazvin on September 26th, 1931. He studied pharmacy at the University of Tehran; then, upon graduation, he received a Master’s of Philosophy. After the military coup of 1953, which deposed the government of Mohammad Mossadegh, Yazdi joined the underground National Resistance Movement of Iran. This organization strongly opposed the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Yazdi traveled to the United States in 1961 to continue his education and in the US, continued his involvement in political activities against the monarchy. In 1975, Yazdi was tried in absentia in an Iranian military court and condemned to ten years imprisonment, with orders issued for his arrest upon return to Iran. Because of his activities, he was unable to return to Iran and remained in the United States until July of 1977. He became a naturalized US citizen in Houston in 1971, but later agreed to return to his homeland to participate in the new, republican government. After being granted a pardon by the provisional government, Yazdi then joined the Foreign Ministry, and became a member of Prime Minister Bazargan’s Freedom Party.

Many world leaders, who swiftly called Yazdi to congratulate him on his electoral victory, wondered what sort of man this new Prime Minister would be. Iran was, after all, a middle and regional power. Bazargan and the provisional government had sworn neutrality in the Cold War, and had begun pushing Iran toward the Non-Aligned Movement. But there were many within Tehran, Moscow, and Washington who hoped for the republic to take a different path.

For one thing, geopolitics made prolonged Iranian neutrality difficult. To Iran’s east lay Soviet-aligned Afghanistan and Pakistan. To its west, stood the United Arab Republic, another Soviet ally. Control of the Persian Gulf and with it, the vast oil resources of the Middle East was far too tempting an opportunity for the world’s superpowers to pass up. Both US Secretary of State George Ball and Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko understood that the energy crises of the 1970s were largely the result of instability in the Middle East. Though the Udall Administration had taken great pains to begin to cure America of its addiction to foreign oil, it would take several years, if not decades, for their efforts to pay off. In the meantime, the world’s hunger for energy meant that the Middle East, and its resources, remained crucial.

Given that Yazdi was a naturalized US citizen, and had spent many years in the United States pursuing his education and remaining safe from the Shah’s regime, many in Washington and Moscow assumed that he would, naturally, favor rapprochement with the US. These experts were largely correct in this assessment.

Yazdi pointed to the Udall Administration’s condemnation of the Shah and refusal to back him, as well as the historical precedent of the Kennedy Doctrine as proof that America would now support Iran pursuing their own national interest, as defined by their democratically-elected government. Others in Tehran, however, even including members of his own ministry, were less certain. Memories of 1953 were still firmly held. America had been quick then to discard her dedication to democracy in the name of imperial interests, alongside the British. Thus, for as friendly to the US as Yazdi was, he knew that he could not pursue a Western alignment too strongly, or too quickly. He was head of an unsteady coalition, the only thing (in his mind) standing between Iran and an Islamic theocracy (led by Mostafa Khomeini) or a Soviet-backed Communist coup.

As if this situation were not shaky enough for the new government, a crisis emerged in September of 1980 that would test the very foundations of the Democratic Republic - war with the UAR.

…

Above: The Khuzestan Province in Iran, which the United Arab Republic planned to annex (left); the Shatt al-Arab on the Iran-UAR border (right).

Above: The Khuzestan Province in Iran, which the United Arab Republic planned to annex (left); the Shatt al-Arab on the Iran-UAR border (right).

In April 1969, Iran abrogated the 1937 treaty over the Shatt al-Arab (a 120 mile long river at the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates that flows into the Persian Gulf), and Iranian ships stopped paying tolls to Iraq when they used the river. The Shah argued that the 1937 treaty was unfair to Iran because almost all river borders around the world ran along the thalweg, and because most of the ships that used the Shatt al-Arab were Iranian. Iraq threatened war over the move at the time, but on April 24th, 1969, an Iranian tanker (escorted by Iranian warships) sailed down the Shatt al-Arab into the Gulf. Iraq - being the militarily weaker state - did nothing. Though from Iran’s perspective, the issue appeared to be settled, from Iraq’s (and subsequently, the UAR’s), it was anything but.

The Iranian Revolution of 1978-79 reopened the issue, and inflamed tensions between the two nations once again.

Initially, Hussein and Assad were pleased by news that the Shah, their old enemy, had been overthrown. This feeling swiftly dissipated, however. The new republican government in Tehran refused to revisit the issue of the Shatt al-Arab, which it likewise considered to be settled law. Further, there were cultural and religious tensions as well.

Though officially a secular nation, Iran, with its largely Shia population, represented the branch of Islam opposite Saddam Hussein. For Shia Iraqis, the Revolution - which overthrew an unpopular tyrant “forcing” secularization upon an unwilling, conservative populace - seemed like it could serve as an inspiration. Hussein was terrified of this possibility. Thus, in Saddam’s mind, crushing Iran, humiliating them utterly, was an utmost priority.

His diplomatic play over the Shatt al-Arab (and to annex the Khuzestan province) began in February with an ultimatum issued by his ambassador in Tehran. In the brash, provocative text of the document, Saddam demanded that Iran cede the region to the UAR “as a show of good faith toward continued friendship between our nations”. Yazdi’s government, assuming the play to be some kind of saber-rattling bluff, refused to respond. The Prime Minister did, however, authorize back channel talks to try and arrange for a summit between himself and Hussein to “renegotiate a mutually beneficial relationship along the Gulf”. Hussein likewise rebuffed these talks.

On March 8th 1980, the time-limit on the ultimatum ran out. The UAR announced that it was withdrawing its ambassador from Iran, downgraded its diplomatic ties to the charge d'affaires level, and demanded that Iran do the same. In response, the following day, Iran declared the UAR’s ambassador persona non grata, and withdrew their own ambassador.

Slowly, the drums of war began to beat.

On the eve of the revolution in 1978, international experts in military science had assessed that Iran's armed forces were the fifth most powerful in the world. (Behind the United States, Soviet Union, United Kingdom, and France). With a well-trained officer corps and large stockpiles of high quality American and British-made equipment, the Iranians seemed like a truly fearsome opponent for any nation that dared to take them on. In the aftermath of the Shah’s abdication, however, the military was rocked by a series of successive blows that severely weakened their position.

First, as the Bazargan-led Provisional Government attempted to join the Non-Aligned Movement, the political cost of continuing to purchase Western military equipment rose. In an attempt to secure the new government’s supposedly neutral footing, all shipments of military aid from the West were ordered to cease. This resulted in a shortage of spare parts, especially for vehicles like tanks, armored personnel carriers, and crucially, the American-made F-14 Tomcat fighter jets. Though the Yazdi government quickly attempted to remedy this and would do so after the outbreak of war in September, in the months leading up to the Iraqi invasion, Iranian equipment and logistics were unnecessarily weakened by a lack of supply. See the comparison below:

Imbalance of Power (Sept. 1980):

Number of Soldiers

United Arab Republic - ~350,000 - 24 divisions and nine brigades

Iran - ~415,000 - 28 divisions and five brigades

Tanks

United Arab Republic - ~3,000

Iran - ~2,000 (Approximately 1,000 of which were operable)

Fighter Aircraft

United Arab Republic - 362

Iran - 455 (350 operable)

Helicopters

United Arab Republic - 150

Iran - 500 (200 operable)

Artillery

United Arab Republic - 1,000

Iran - 1,000 (300 operable)

Above: Iranian Mobarez (“Warrior”) tanks, modeled on the British Chieftan (left); American F-14 Jet Fighters, the jet of choice for the Iranian air force in 1980 (right).

Second, along with the rest of Iranian society, the military was still rife with internal divisions and shifting loyalties amidst the relative chaos of transitioning from a constitutional monarchy to a democratic republic. Though most major generals and other senior staff officers remained after the Shah’s abdication and the unveiling of the new constitution, many rank and file soldiers were unsure about the future of their country. Some held views sympathetic to the radical Islamists whom they felt were “ostracized” by Yazdi’s government, as he had not invited them to join the Grand Coalition. Even those soldiers that did support the new republic (including most of the officers) felt that the country was not ready for any kind of armed conflict. One general summed up the military’s assessment of Iran’s defense when he wrote to Prime Minister Yazdi in May 1980:

“At this time, we are best suited by taking a firmly defensive posture with our neighbors. We claim that our position is not to stand alone in the world, but will any of our fellow ‘unaligned’ powers come to our aid in a time of crisis? I think not.”

Meanwhile, UAR military intelligence reported in July 1980 that despite Iran's optimistic rhetoric, “it is clear that, at present, Iran has no power to launch wide offensive operations against us, or to defend on a large scale.” Saddam, upon reading the report in his office at the Presidential palace in Baghdad was said to have smiled wide. Days before the UAR’s invasion and in the midst of rapidly escalating cross-border skirmishes, UAR military intelligence again reiterated on September 14th that “the enemy deployment organization does not indicate hostile intentions and appears to be taking on a more defensive mode.”

In addition, the area around the Shatt al-Arab posed no obstacle for the Iraqis and Syrians, as they possessed river crossing equipment. The UAR correctly deduced that Iran's defenses at the crossing points around the Karkheh and Karoun Rivers were undermanned and that the rivers could be easily crossed. Arab intelligence was also informed that the Iranian forces in Khuzestan Province (which consisted of two divisions prior to the revolution) now only consisted of several ill-equipped and under-strength battalions. Only a handful of company-sized tank units remained operational.

On September 10th, 1980, the UAR acted on these reports, and forcibly reclaimed territories in Zain al-Qaws and Saif Saad that Iraq had been promised under the terms of the 1975 Algiers Agreement, but that Iran had never handed over, leading to both Iran and the UAR declaring the treaty null and void, on September 14th and 17th, respectively. As a result, the only outstanding border dispute between Iran and UAR at the time of the UAR invasion of September 22nd was the question of whether Iranian ships would fly UAR flags and pay navigation fees for a stretch of the Shatt al-Arab river spanning several miles.

…

Above: UAR forces pummel the disorganized defenders of Shush, a city in the Khuzestan Province of Iran with artillery (left); Iranian F-14 Tomcats are scrambled to protect Tehran from air attacks (right).Saddam launched a full-scale invasion of Iran on September 22nd, 1980, beginning in the air.

The UAR’s Air Force launched surprise airstrikes on ten Iranian airfields with the objective of destroying the Iranian Air Force. The attack failed to damage the Iranian Air Force significantly. It damaged some of Iran's air base infrastructure, but failed to destroy a significant number of aircraft. Saddam’s Air Force was only able to strike in depth with a few of his jet fighters. Iran had also built hardened aircraft shelters where most of its combat aircraft were stored.

The next day, a ground invasion followed along a front measuring 644 km (400 miles) in three simultaneous attacks. Saddam hoped an attack on Iran would cause such a blow to Iran's prestige that it would lead to the new Yazdi government's downfall.

Of the UAR's eight divisions that invaded by ground, six were sent to Khuzestan, which was located near the border's southern end, to cut off the Shatt al-Arab from the rest of Iran, as well as to establish a “territorial security zone”. The remaining two invaded across the northern and central sections of the border to prevent a counter-attack.

Two of the six UAR divisions, one mechanized and one armored, operated near the southern end of the border, and began a siege of the strategically important port cities of Abadan and Khorramshahr. On the central front, Saddam’s troops occupied Mehran, advanced towards the foothills of the Zagros Mountains, and were able to block the traditional Tehran–Baghdad invasion route by securing territory forward of Qasr-e Shirin, Iran. To the North, the UAR attempted to establish a strong defensive position opposite Sulaymaniyah to protect the oil complex at Kirkuk. Saddam had hoped that ethnic Arabs in Khuzestan would rise up in rebellion and join their “liberators” against Iran, but this failed to materialize. The vast majority of ethnic Arabs in the area remained loyal to Tehran.

Western military observers would later characterize the entire invasion as “badly led” and “consisting of troops with staggeringly low morale for such an enterprise”. The latter of these observations could, perhaps, be attributed to the fact that many of the UAR’s rank and file soldiers were Syrian conscripts, who felt little to no attachment to their new president and his dreams of hegemony. Saddam did not fully trust Assad, and so refused to let his own “Republican Guard” units, fully loyal to Saddam, be sent to the front. The Guard remained in the rear, never far from Baghdad.

Perhaps attempting to make up for his troops’ low morale, Saddam authorized the use of chemical weapons against the Iranians, a clear violation of the Geneva Convention and other statutes of international law. The first known instance probably took place during the fighting around Shush.

Though the UAR’s air invasion took the Iranians by surprise, the Iranian air force retaliated the following day with a large-scale counterattack against Arab air bases and infrastructure. Groups of F-4 Phantom and F-5 Tiger fighter jets attacked targets throughout Iraq, including oil refineries, dams, and petrochemical plants. Another set of targets were Mosul Air Base, Baghdad, and the Kirkuk oil refinery. The UAR was shocked at the strength of the retaliation, which caused heavy losses and severe economic disruption, but the Iranians took heavy losses as well as losing many aircraft and aircrews to Arab air defenses.

Meanwhile, UAR air attacks on Iran were repelled by Iran's F-14A Tomcat interceptor fighter jets, using AIM-54A Phoenix missiles, which downed a dozen of the UAR's Soviet-built fighters in the first two days of battle alone. Though Iranian ground forces scrambled to deliver a coordinated counterattack, the Navy attacked Basra, Iraq, destroying oil tankers near the port of Al-Faw, reducing the UAR’s ability to export oil, a critical economic lifeline. In general, Tehran ordered a general retreat of ground forces to the cities, where they could dig in and organize a defense. This left the countryside to the invaders, who often looted, pillaged, and committed other atrocities against the civilian population.

The mountainous border between Iran and Iraq made a deep ground invasion almost impossible by either side. Thus, air strikes and long-range artillery were used instead. The invasion's first waves were a series of airstrikes targeted at Iranian airfields. The UAR also attempted to bomb Tehran into submission.

On September 22nd, a prolonged battle broke out in the city of Khorramshahr, eventually leaving around 7,000 dead on each side. This led to Khorramshahr gaining the nickname, “the City of Blood” amongst Iranian soldiers. The battle began with Saddam’s armored and mechanized units approaching the city in a sickle formation, only to be beaten back by fierce resistance. Iranians, many armed with improvised weapons and Molotov cocktails, fought back the invaders house by house, and street by street. Arab air superiority became the deciding factor, however, and by September 30th, the outskirts of the city had been overrun. Over the next month, the fighting continued until at last, on the 24th, the beleaguered Iranians withdrew, surrendering the city.

Despite the setback, however, the Iranians used the delay granted them against the invaders to fully mobilize and deploy their armed forces. When Saddam ordered his troops to advance toward Dezful and Ahvaz, his units were badly damaged by revitalized Iranian air power and artillery strikes. The Iranian air force struck the invaders’ supply depots, robbing them of vital fuel and water. Simultaneously, in November, Iran launched Operation Pearl, a combined sea and air attack that wound up destroying approximately 75% of the UAR’s naval presence in the Persian Gulf, along with most of its southern radar sites. When the Arabs laid siege to Abadan, they were unable to blockade the port, allowing the city to be resupplied via the sea.

Quickly, Saddam’s strategic reserves of gas and equipment were depleted. His republic lacked the resources necessary to carry on any further offensives for the rest of the year. On December 7th, 1980, Saddam ordered a general halt on the front, and for his forces to defend “all captured territory” and prepare Khuzestan for “complete annexation by the conclusion of the following year [1981].”

…

Above: Kurt Waldheim, Secretary General of the United Nations (left); Saddam Hussein, President of the United Arab Republic (center); Andrei Gromyko, Foreign Minister of the Soviet Union (right).Diplomatically, the Iran-UAR War became a hot button issue, another flashpoint in the Cold War.

In New York, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution calling on both Baghdad and Tehran to “settle any and all disputes peacefully, submitting them, if necessary, for arbitration in the Hague”. Andrew Young, American Ambassador to the UN, decried this resolution as “weak and needlessly vague in its condemnation”. So far as the US was concerned, blame for the war lay squarely at the feet of Saddam Hussein and his insatiable ambition. The USSR, however, disagreed.

Shortly after the war began, Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko made a top secret trip to Damascus to meet with Hussein and Assad to lend his and his country’s support. The New Troika had hoped to bring Iran under the Soviet sphere of influence, but the defeat of the far-left coalition at the ballot box early in 1980 seemed to make such a shift unlikely. Instead, Gromyko and his fellows in Moscow calculated that by supporting Saddam’s invasion, they may be able to drive the American-friendly Yazdi from power. It was a sort of three-dimensional chess, thinking that they could make Tehran amenable to Soviet interests by force. But it was what they had.

The Soviets voted against condemning Saddam alone for the invasion in the UN, claiming that Tehran had “refused to submit legitimate territorial and economic concerns to international courts for arbitration”. Further, they increased their shipments of military equipment and spare parts to the UAR, allowing Saddam’s forces (in the early stages, at least) to repair and replace their damaged equipment far quicker than the non-aligned Iranians.

Generally speaking, the American public were largely against any kind of military response to Iraq’s invasion. Most saw the war as far-off and far removed from them and their daily lives. Many in Washington, however, grew nervous. Conflict in the Persian Gulf sent already high oil (and therefore gasoline) prices even higher. To prevent a spike in inflation, which had only just gotten under control, Udall authorized a small release from the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve, and encouraged the Federal Reserve to keep interest rates high. This was merely a band-aid on the problem, however. In the long run, a diplomatic solution was necessary.

The war thus, unsurprisingly, became a campaign issue in the 1980 election.

Both Ronald Reagan and Bob Kennedy favored increasing shipments of aid to the Democratic Republic of Iran, though they disagreed on the particulars. Reagan called for Iran to “publicly denounce the Soviet Union and stand beside the free peoples of the world” before it could expect substantial American aid. Kennedy, meanwhile, shied away from such imperialist language, and instead called for “immediate aid and unequivocal support not just for Iranians, but for freedom-seeking people everywhere in the world”. For their part, the Iranian people seemed to prefer Kennedy over Reagan, as the former had a reputation as a hotheaded hawk, while the latter was seen as cool, calm, and collected in a crisis. RFK had also been a nemesis of the Shah during Kennedy’s brother’s administration, further increasing his credibility among the post-revolution Iranian populace.

Negotiations did begin between Ebrahim Yazdi and Mo Udall’s respective administrations to start the crucial shipments of spare parts flowing. But major shipments would not be ready until the following year. Until then, both Iran and the UAR settled in for what they feared would be a long, bloody conflict.

Next Time on Blue Skies in Camelot: The 1980 Presidential Election

Share: